When we are told to think of college activism that has had a long-lasting impact on the entire world, many of us might first think of the Vietnam War. In this sense, Smith is very similar to other colleges nationwide — the Sophia Smith Collection contained endless information on Smith student activism against the Vietnam War, and even had a full box devoted to the Student Strike of 1970 organized in order to advocate for an end to the war.

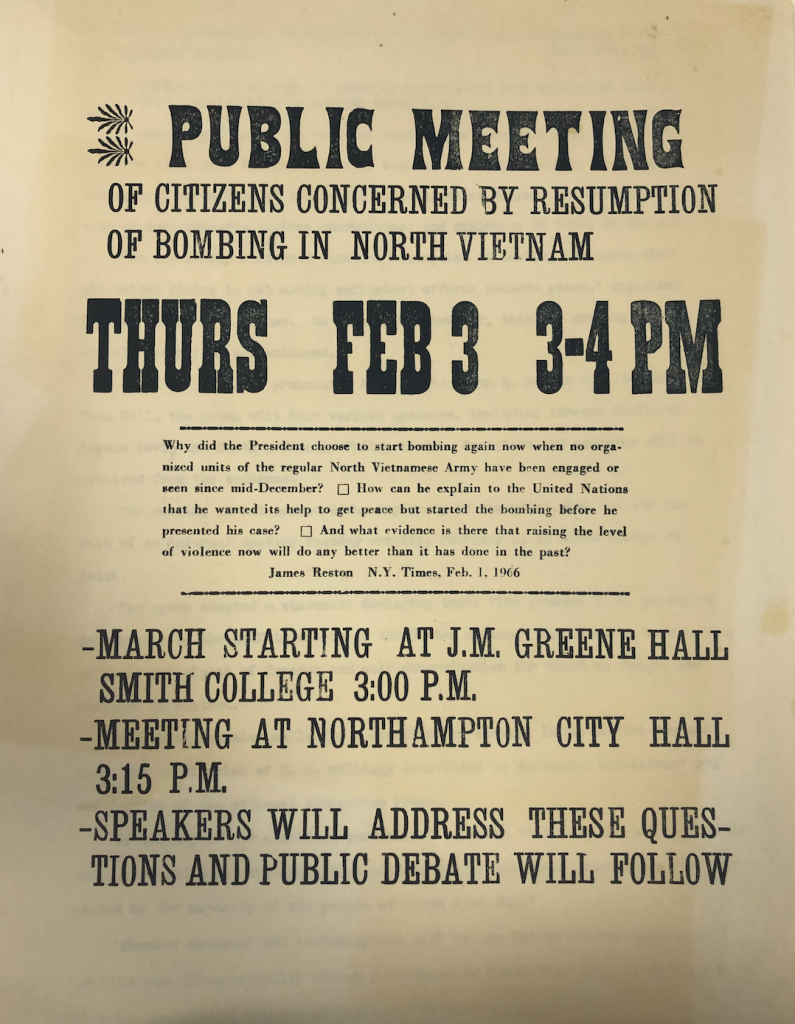

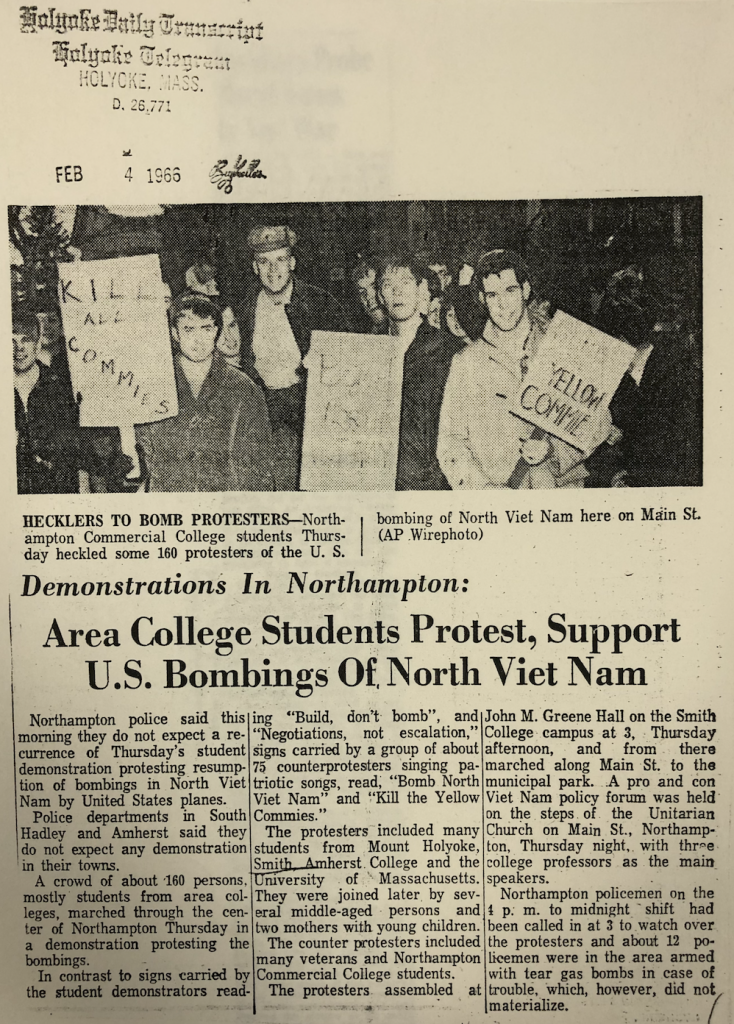

In another sense, of course, Smith had a large distinction from the vast majority of other colleges in the United States: as a historically women’s college, its students were essentially immune to the draft (for themselves, at least). Even though as a result Smith’s anti-draft protests had slightly less skin in the matter, many Smith students had brothers, friends, cousins, and boyfriends that were at risk of being drafted into the Vietnam War. Students led a considerable amount of marches, rallies, and protests both against the draft and the war itself, claiming it was inhumane and morally repugnant on the part of the United States. When its protests reached downtown Northampton, local residents and college students from the surrounding area would sometimes clash with them in a pro vs. anti-war encounter.

The Vietnam War was one of the most polarizing events in 20th century American history, of course, and not even Smith’s own campus was unified in its disapproval. Several Smith professors appeared on a list of liberal arts college professors that approved of the U.S. government’s handling of the war in Vietnam, further straining wartime relationships on campus.

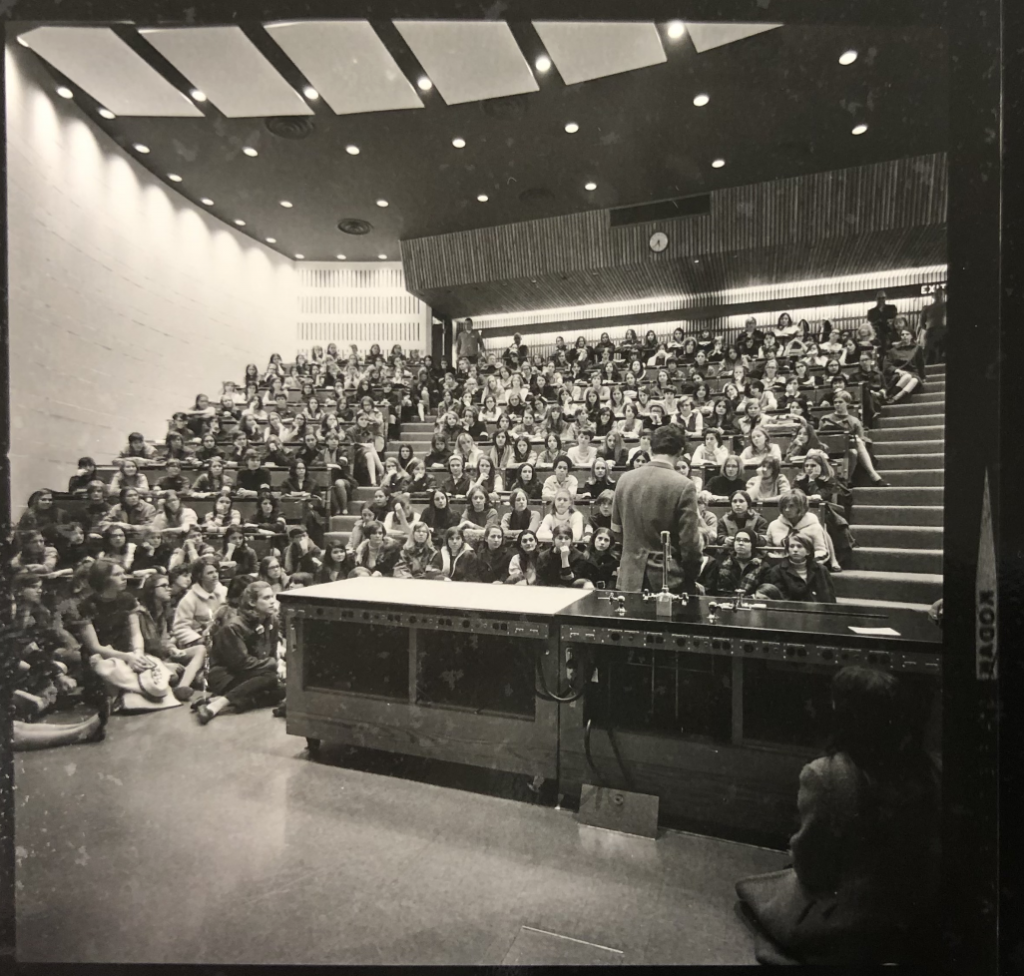

Since Smith students couldn’t express their disdain toward the war by dodging the draft, they chose to draw attention to their anti-war sentiments through a fast for peace. By consuming an exclusively liquid-based diet for three days, Smith students hoped to garner enough media attention to cause people to reevaluate their own feelings about the war. Fasters wore green armbands and their non-fasting allies wore white ones to signal their support. Professors and student organizers made speeches over the course of the fast, further fostering a sense of belonging and inclusion on campus during those few days. Newspapers from the Pioneer Valley to Palo Alto reported on the fast, drawing widespread attention from American society.

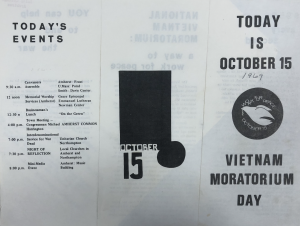

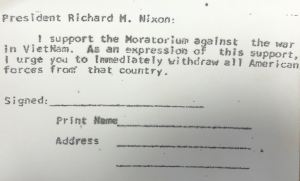

The peaceful civic protests continued throughout the late ’60s, with Smith students participating in the Vietnam Moratorium Day on October 15, 1969. Across the Pioneer Valley there were teach-ins, rallies, speeches, and collective meditations on the violence of the Vietnam War and possible ways to accelerate its end. Students distributed flyers and spoke to passersby on the streets in order to try to communicate their message to as many people as possible.

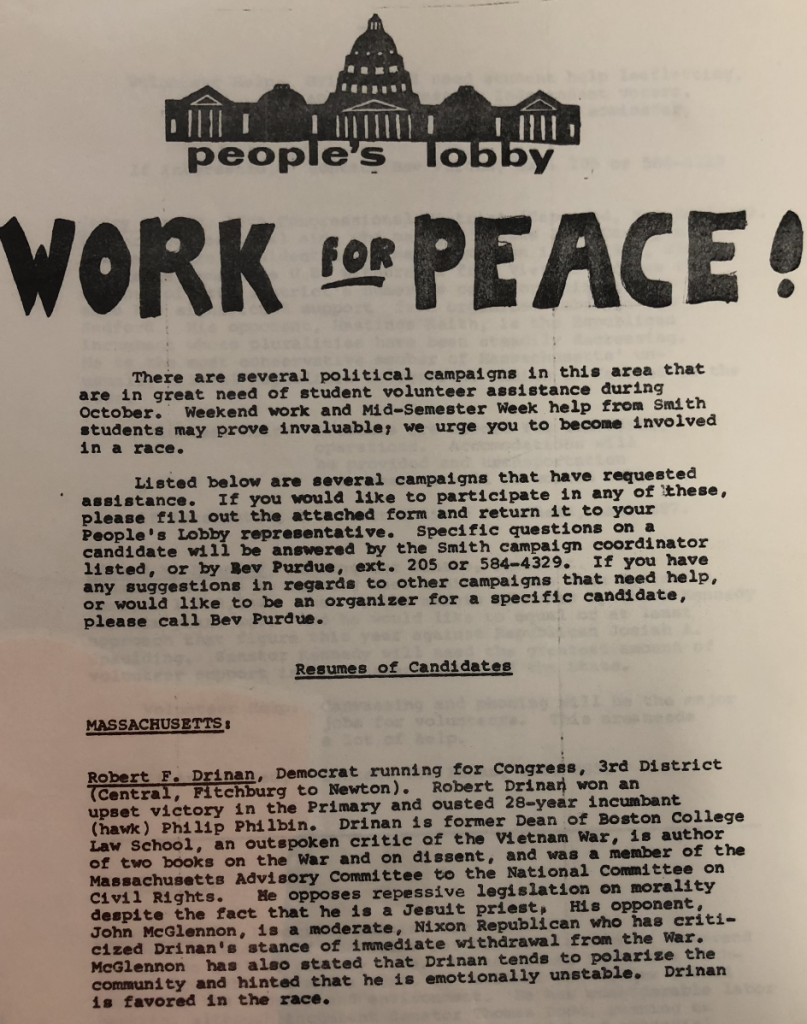

The original intention was to make the moratorium a monthly event, adding a day each month until the war was over. While it is unclear if the moratorium became a longterm event for Smithies, student organizers came together to form The People’s Lobby, a group dedicated to raising awareness about the continuing impact of the Vietnam War and advocating for its end. The group organized a new “Work for Peace” day in 1970, in which Smith students from across the country worked to help their local anti-Vietnam War candidates win their elections.

Although Smith students may not have been able to engage in the direct defiance of the war enabled by the ability to dodge the draft, their civil protests and work to bring attention to the atrocities of the Vietnam War were unquestionably an incredibly important part of the mythology and history surrounding college activism against the war.