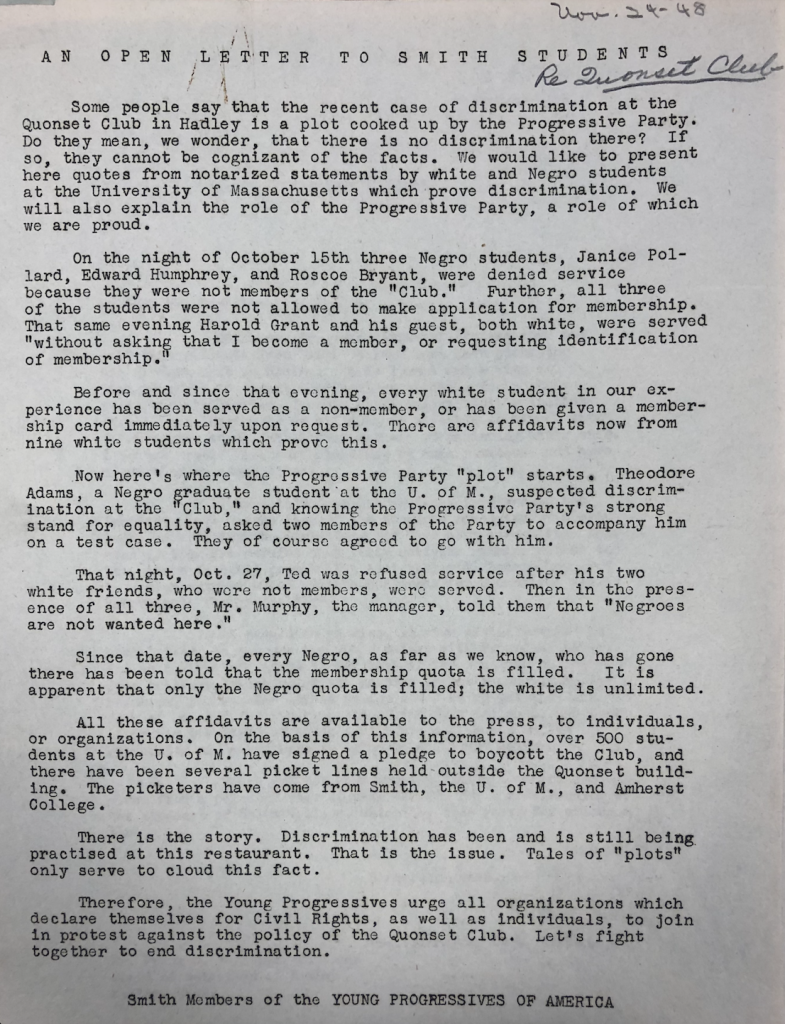

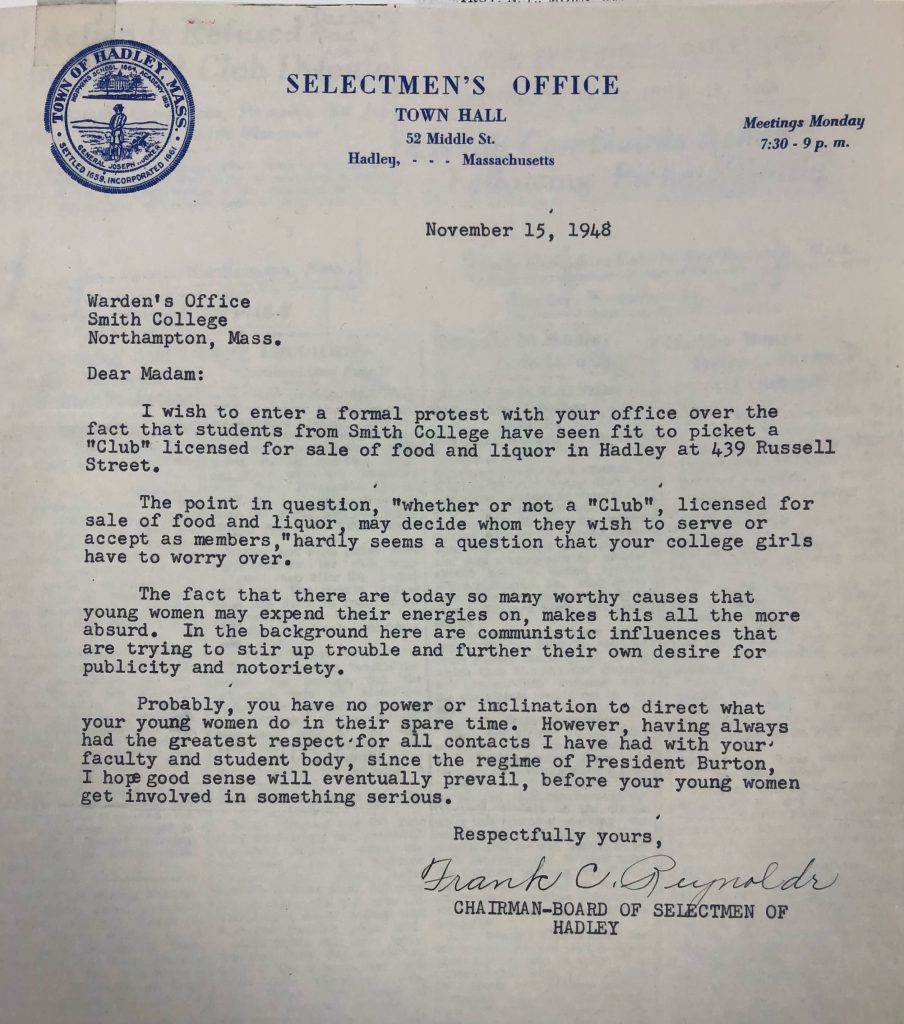

As early as the 1940s, Smithies were getting involved in matters of racial justice and equality. The Sophia Smith Collection’s earliest evidence of Smith student involvement in protesting racism and segregation is an incident from 1948 in which several white Smith students from the Smith Young Progressives of America club joined students from the University of Massachusetts in Amherst in an effort to boycott the Quonset Club in Hadley over its refusal to serve Black students. It was so effective and disruptive that the club’s owner even wrote to the Smith College Warden to complain about the boycott, claiming that communistic ideas were influencing the girls’ decision.

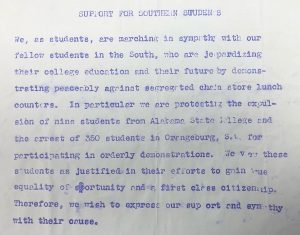

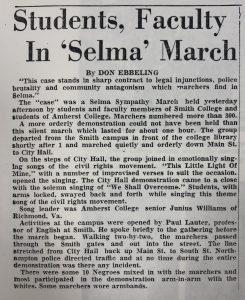

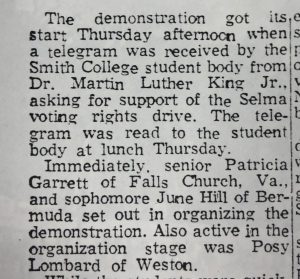

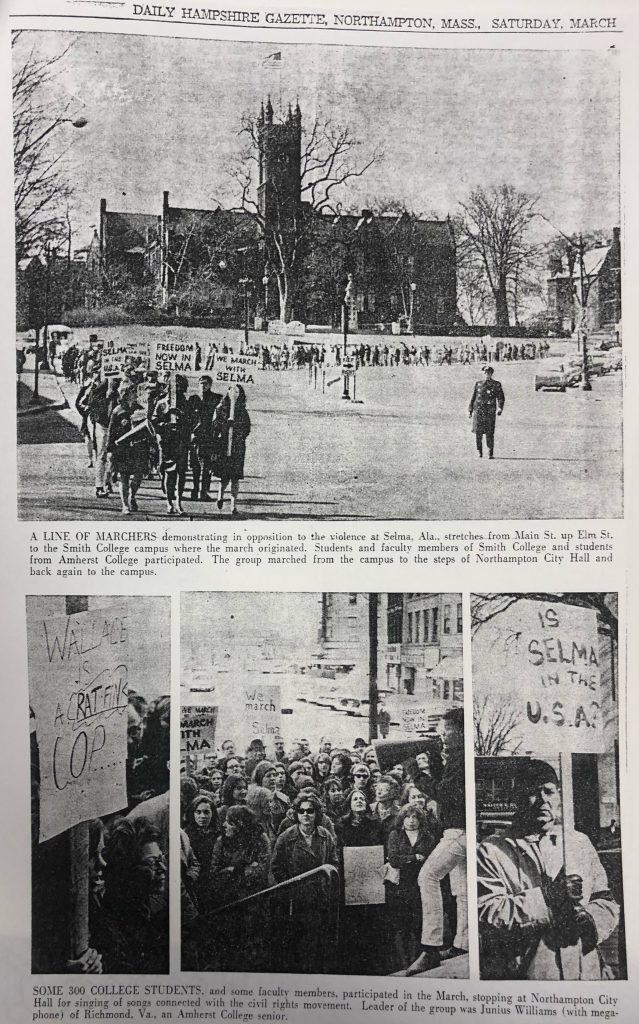

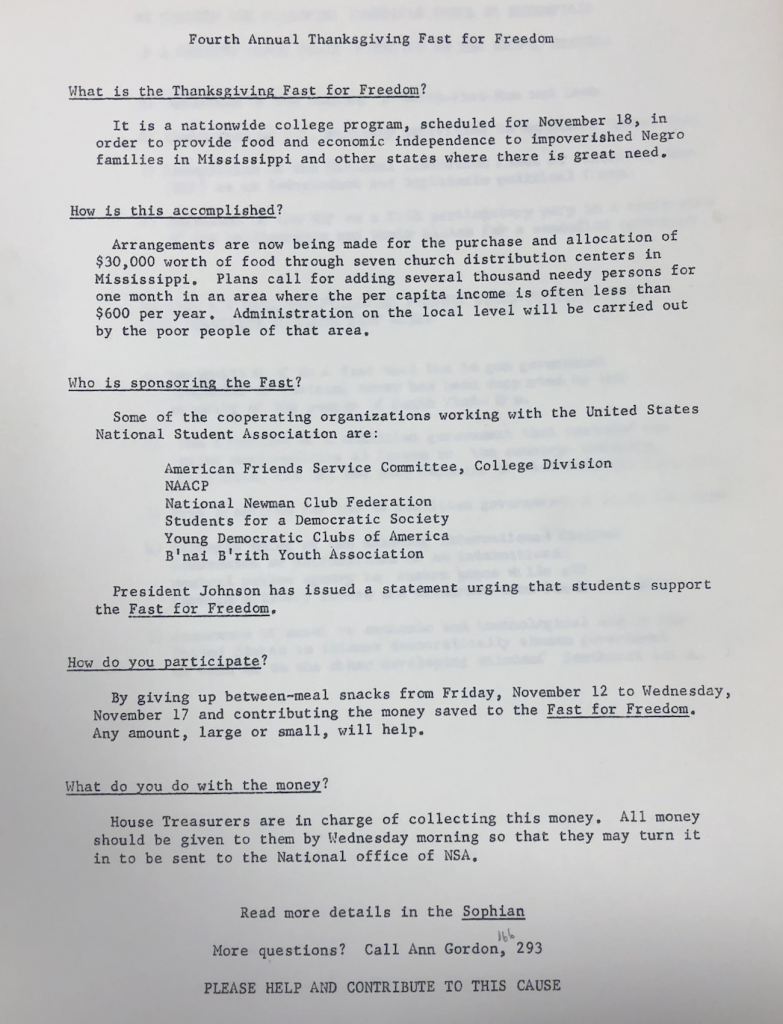

With the advent of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s came heightened levels of Smithie involvement in the push for racial equality in America. Smith students both participated in and organized their own marches through campus and downtown Northampton protesting for voting rights for Black people, and some Smith students and faculty members traveled to Selma, Alabama, to march alongside Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1965. Smith students also participated in the Fast for Freedom, an annual event on college campuses nationwide where students would skip any “between-meal snacks” for a week and instead donate the money saved to a fund to provide food for impoverished Black families in the American South, specifically Mississippi. By drawing attention to the issues of civil rights and racialized poverty through the only mediums they had available to them as young female students (marching and fasting), they were able to push those with more power and agency to act upon the same issues.

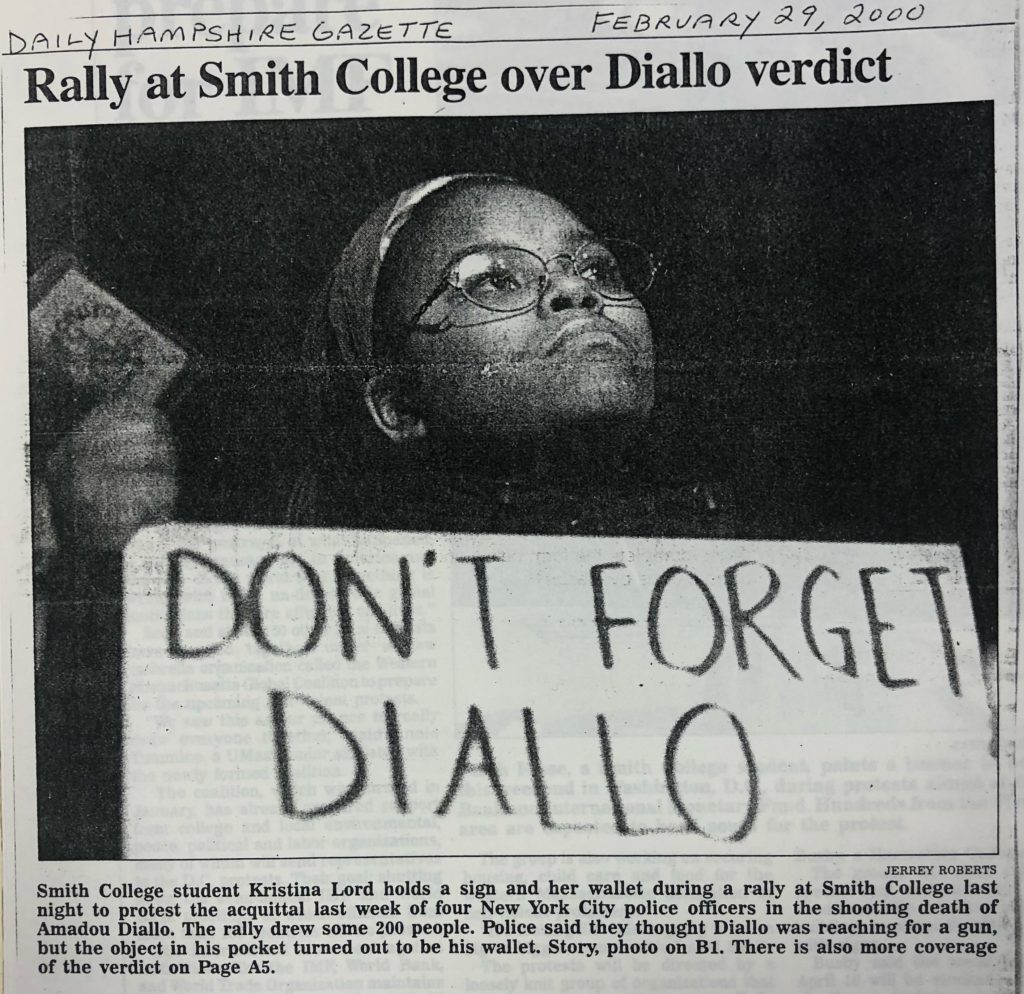

In the 1990s, the epidemic of police violence against Black men became a cause for protest on Smith’s campus. Following both the Rodney King verdict in 1992 and the Amadou Diallo verdict in 2000, Smith students gathered to protest national injustice and systemic racism, holding signs saying “U.S. Justice is a Fucking Farce” and “Don’t Forget Diallo.” This work has continued well into the 21st century, with Smith students becoming heavily involved in the Black Lives Matter movement and the movement to defund/abolish the police/end police brutality.

In 2014, President McCartney’s email responding to the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner contained the subject line “All Lives Matter,” a phrase coopted by those intending to detract from the power and message of the Black Lives Matter movement. Regardless of her follow-up apology, tensions surrounding racial and police violence began rising on campus. In the summer of 2018, a staff member called campus police on a Smith student who was in the living room of a residential house that was technically closed for the summer. The subsequent media frenzy surrounding the event further heightened racial tensions on campus, at one point spilling over in the walk-out staged at 2018 Convocation to protest the event’s handling and the student’s treatment by the college.

This incident still looms large in the Smith consciousness, not least of all because of a staff member named Jodi Shaw recently reintroducing the events of the summer of 2018 into the public eye. Her bogus claims of Smith’s racism against white members of the staff and their attempts to silence her have led to outlets like the New York Times and Fox News rehashing the events of that summer under a newly scrutinous eye in the age of “cancel culture.” Not only have Shaw’s actions forced the student to relive one of the more traumatic experiences of her life, but they have also launched a renewed reckoning over race relations on liberal arts college campuses. As Smith continues to grapple with issues of race on campus and within the higher ranks of its administration, Smith students continue to push toward racial equity and understanding on campus and in the larger world.