Residence at Smith College

Smith College, a small liberal arts women’s college in Northampton, Massachusetts founded in 1871, created spaces for intimate connection between women. At the end of the nineteenth century the women faculty at Smith College lived amongst their students. This arrangement kept women from having the private lives that male faculty members were afforded. Among women’s professional duties in these household, was tending to the personal lives of their students and setting “the intellectual and social tone at the dinner table and the parlor.”1

In the early twentieth century, some women faculty at Smith were able to move out of student residences and into their own homes. Historian Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz described that, “as women left the residence hall they generally withdrew in pairs of friends to apartments or houses, to which the women of their families were usually invited. They were the first generation of American women able to support themselves and buy houses…These domestic structures provided them with physical confirmation of their existence, their independence, and their intimacy with other women. Their libraries, dining rooms, and gardens offered inviting places for stimulating talk, refreshment, and relaxation.“3

Tea Parties

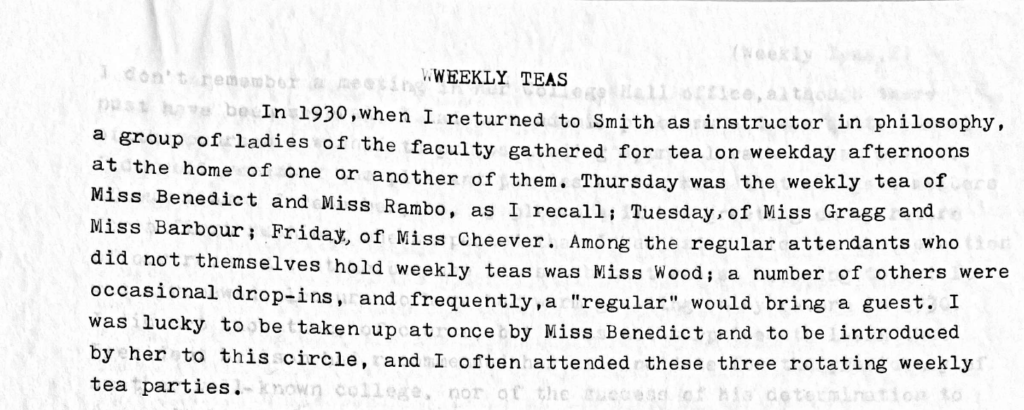

The description written by Margaret Storrs Grierson (1900-1997) Smith College’s former archivist describes weekly teas which were attended and hosted by Smith College faculty women in their off campus homes. The women described above are Smith College faculty members; Classicists Florence Gragg and Amy Barbour, Mathematicians Suzan Benedict and Susan Rambo, and Writer Louisa Cheever. All except Florence Gragg ( a Radcliffe College graduate) graduated from Smith College in 1890-1905 and subsequently returned to Smith as faculty members between 1900-1910.

Smith was a site of refuge and home making for these women, from undergraduates to faculty members, women returned to Smith to build their intellectual and familial lives. Mostly this did not include children, but networks of women faculty and staff from Smith and other Smith College Graduates.

In 1922, Smith graduates made up 26 per cent of the 265 faculty members and women outnumbered men on the faculty; that same year there were 62 men on the faculty and 203 women.4

Non-Biological Family

Current understandings of non-traditional family and queer family are described as “the concept of families of choice [which] refers to the ways in which all manner of relationships (including couples, ex-partners, friends, accepting family of origin, co-parents, LGBTQ community members, and so on) can be included as family.”5

Amy Barbour and Florence Gragg’s life at Smith not only included a shared home at 234 Crescent Street in Northampton, but also shared sabbaticals and adopted children. During their travels to Greece the two women adopted children who were orphaned during the destruction of the city of Smyrna in 1922. While it is unclear how prevalent adoption was amongst single women in the early twentieth century the women who did “often raised their adopted children with female partners or within a community of women.”6

Before queer and feminist scholars conceptualized the terms queer family or chosen family, Gragg and Barbour’s were conducting their lives according to this alternative family model. Their mutual adoption of children can be understood as an early example of what is now more widely acknowledged as a queer familial structure. The strong connection between women faculty at Smith and their students beyond graduation could be interpreted in this manner as well. In Gragg and Barbour’s case their intergenerational ties to the younger Smith College graduates Marion Guptill (class of 1926) and Alison Frantz (class of 1924) can be understood as an extension of the Smith College family.

For the Future Generations of Women

In 1918, Ruth Wood advised Margaret S. Grierson, then an undergraduate student at Smith against pursuing a career in Mathematics because “women were not given fair play in the field.” While Margaret S. Grierson’s description of Ruth Wood might lend to an interpretation of Ruth as an unenthusiastic professor, Ruth Wood’s 33 year career at the college might say otherwise. Joining the Smith faculty in 1902 Ruth did not retire until 1935.

Upon her death in 1939 Ruth Wood’s friends and fellow professors Suzan Benedict, Florence Gragg, and Susan Rambo described her lasting impact on her students; “Many generations of students have found stimulus in her friendly criticism, encouragement in her sympathetic understanding, inspiration in her scholarship. Her colleagues have profited by her ready cooperation, keen intelligence and substantial common sense. No one of them can forget her sturdy insistence on careful thinking and honest dealing.”6

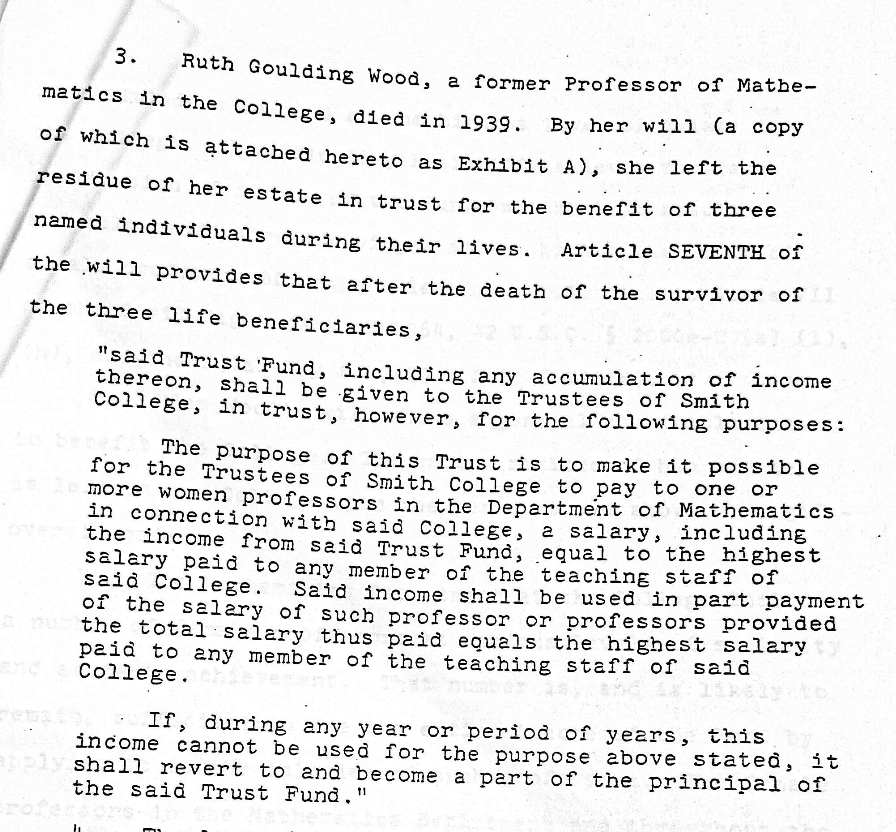

Ruth Wood’s estate is telling. Her will left a diamond pin to her classmate Adeline F. Wing, Class of 1898 and a share of a trust was to go to Helen Wright, Class of 1905, one of her students. And to the Trustees of Smith College she left $352,000 (which is equal to $7,935,211 in 2025), under the stipulation that the money goes to raising the salary of one or more women professors in the mathematics department to equal that of the highest paid teaching staff at Smith.

Ruth Wood’s will extends the connection between women at Smith beyond generation. We can hear whispers of Ruth Wood’s 1918 advice to Margaret S. Grierson, which Ruth Wood sought to rectify in her will for the future women who would take her place at Smith. Since fair play was not given to her, Ruth Wood tried to even the playing field for the next generations.

Questions

What is your conception of non traditional family in the past? does that differ from your conception today?

Why might non traditional family be significant to queer people?

What conversation can we imagine taking place at the tea parties?

What other kinds of spaces can you think of that give space community gathering?

Further research

To learn more, you can explore:

Smith College Faculty and staff biographical files at the Smith College Archives

Margaret Storrs Grierson papers at the Smith College Archives

Office of President William Allan Neilson Files at the Smith College Archives

Office of the President Jill Ker Conway Files in the Smith College Archives

For another story about women’s educators and companionship in the early twentieth century see the story of Mount Holyoke professors Mary Woolley and Jeannette Marks

Secondary sources

- Berebitsky, Julie. Like Our Very Own : Adoption and the Changing Culture of Motherhood, 1851-1950. University Press of Kansas, 2000. Julie Berebitsky articulates the changing culture around single mother adoption. Particularly relevant to this project is her discuss on the changing ideas around motherhood during between 1900-1940 in the United States. Berebitsky notes that before 1920 there was a general consensus that single women were fit for adoption because of cultural ideas which thought of all women as having motherly knowledge regardless of marital status this idea shifts starting in the 1920s when access to motherhood began to be thought only in connection to sexuality within marriage, single adoptive mothers were seen as suspect.

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s. University of Massachusetts Press, 1984. Horowitz details the difficulty of the late nineteenth century woman professor who was expected to live among the students as a kind of governess and academic role model. Horowitz gives insights to the issues discussed by woman professors at other women’s colleges around living in student residences. Horowitz also touches on changing ideas around sexuality in the early twentieth century. While widely tolerated at Smith, same-sex intimacy began to draw more public scrutiny in the 1910s and 1920s.

- Weston, Kath. Families We Choose : Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. Columbia University Press, 1997. Kath Weston book was the first study of queer chosen family in the United States. Weston emphasizes the importance of close friends in the lives of queer people. Participants in Weston’s study often refer to the importance of friends in their familial support systems.

- Van Dyne, Susan. “”Abracadabra”: Intimate Inventions by Early College Women in the United States.” Feminist Studies 42, 2016. Susan Van Dyne’s essay gives insight into the social culture more so amongst students than faculty in the early 1880s at Smith College. Van Dyne articulates the environment that the group of women in this piece would have encountered during their undergraduate time at Smith, which was marked by the rather new experience of same-sex intimacy outside of family life. Additionally, Van Dyne discusses the case of an English professor Kate Sanborn who published a poem alluding to the women centered and intimate life of students at Smith in the fall of 1881 and was subsequently fired in the Spring of 1882.

Notes and Bibliography

Header Image: Suzan Benedict at her home on 11 Barrett Street, Northampton, Mass. Suzan Rose Benedict papers, Box 678. Smith College Archives, Smith College Special Collections.

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s. University of Massachusetts Press, 1993; 185. ↩︎

- Horowitz, Alma Mater (1993) 190. ↩︎

- Smith College Weekly, 1921 – 1922, Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. And; Catalogues and circulars, 1920-1924, Volume 79, Smith College publications and publications records, Smith College Archives, Smith College Special Collections. ↩︎

- The Sage Encyclopedia of LGBTQ+ Studies, 2nd Edition, edited by Abbie E. Goldberg, SAGE Publications, Incorporated, (2024); 1091. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↩︎

- Berebitsky, Julie. ‘“Mother-Women” OR “Man-Hater”?’ In Like Our Very Own : Adoption and the Changing Culture of Motherhood, 1851-1950. University Press of Kansas, (2000); 105. ↩︎

- Ruth Goulding Wood, Died May 5, 1939. Faculty and staff biographical files. Smith College Archives. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts ↩︎