“Betty bought a Ouija board tonight today,” wrote Alma Routsong (1924-1996) in a journal entry dated Thursday, Oct. 28, 1965. Thus began her years-long use of Ouija board seances, all conducted alongside her girlfriend at the time, Elisabeth “Betty” Deran. Alma was a lesbian author, publishing in the late twentieth century under the pseudonym Isabel Miller. She self-published her first lesbian novel, A Place for Us, in 1969. In 1971, the novel was republished by McGraw-Hill as Patience and Sarah.

Beginning on this fateful night in 1965, Alma and Betty held a series of Ouija board sessions with a wide cast of characters, including Bernard DeVoto, Carl Jung, Gertrude Stein, and, figuring most prominently, the historically elusive Mary Ann Willson and Miss Brundage.1

The Historical Record

Alma based Patience and Sarah on the life of American folk painter Mary Ann Willson, who she discovered while on vacation with Betty. Exploring a museum in Cooperstown, New York, Betty noticed a curious label next to Mary Ann Willson’s painting Marimaid. Betty called Alma over to see: the label noted Willson’s “farmerette” companion, whom she lived with in Greene County, New York in the 1820s. Moved by the idea that Willson lived with another woman, Alma and Betty made their way into the adjoining library and found a book that noted Mary Ann Willson’s “romantic attachment” with a Miss Brundage.2

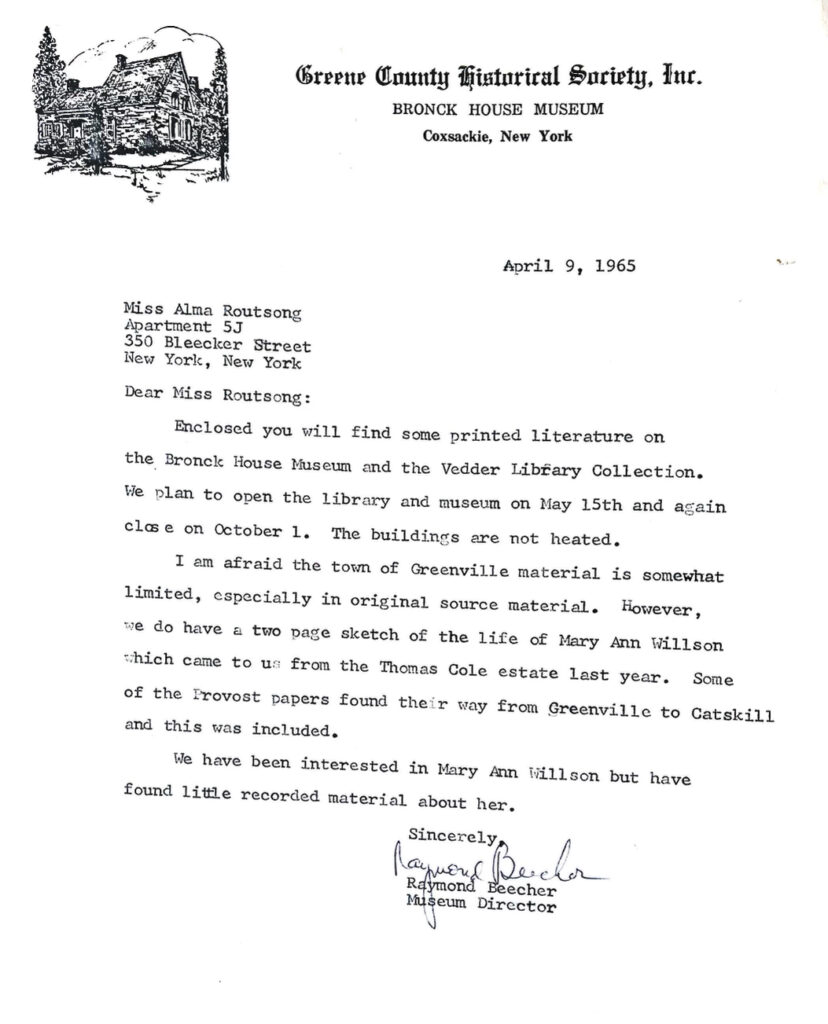

From then on, Alma was fascinated and inspired by the life of Mary Ann Willson. She began to dive into research, attempting to discover more about the painter and her female companion. However, she was dismayed by the lack of information she found as she searched via the Greene County Historical Society and books about American art.3 Even despite her correspondents’ willing assistance, as Raymond Beecher showed in the above letter, there was little information available for Alma to unearth. The historical record had not preserved much about Mary Ann Willson’s life, and even less about that of her companion, for whom Alma could not even find a first name.

Methods of Imagining

So where did Alma get her ideas from? How did she imagine the optimistic queer past that Patience and Sarah represents when she could find such little information on Mary Ann Willson and Miss Brundage?

The answer lies in the Ouija board, the unusual method of imagining that Alma—alongside Betty—landed on when the historical record left her desiring more.

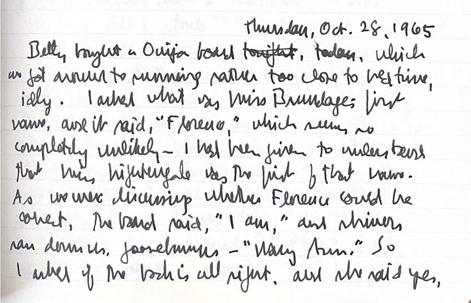

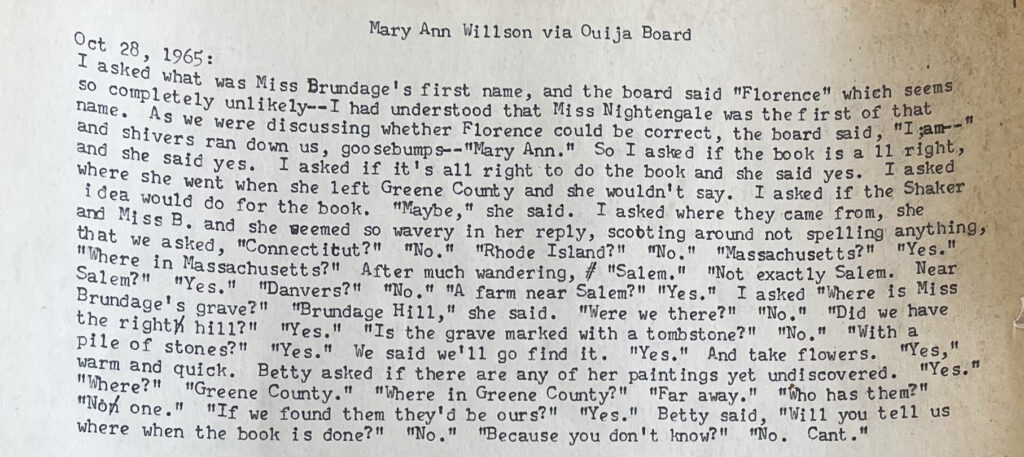

In this first Ouija session, documented by Alma both in her journal and her extensive typed “Ouija notes,” Alma and Betty made contact with Mary Ann Willson, who told them that her companion’s first name was Florence. Though Alma seemed skeptical that Florence could be the right name, given the time period, she also documented the pair’s strong bodily reactions to the experience: “shivers…goosebumps.”

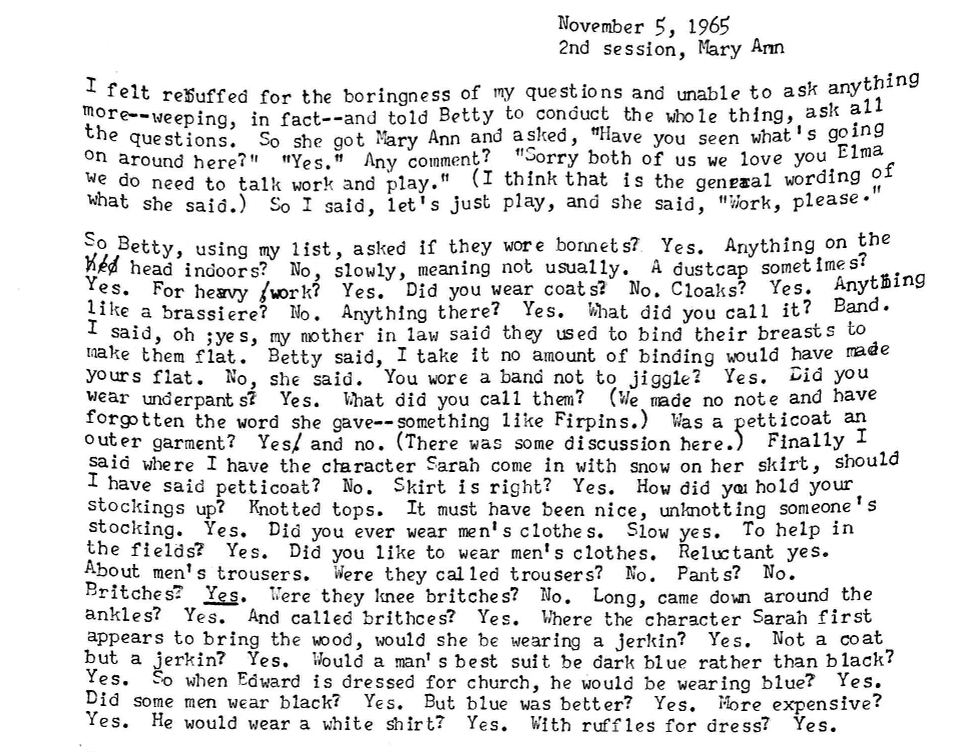

After this first conversation, Alma referred to Miss Brundage as Florence as she and Betty continued the Ouija sessions, inquiring about how Mary Ann and Florence lived and loved: how their neighbors responded to them, the clothes they wore, how they had sex. The details that she generated from the sessions did not just live in her journal and her notes—some of them made their way directly into her writing.

“Something like Firpins”

In Patience and Sarah, Patience sews an undergarment for Sarah: “I am making firpins for you, which I measured you for from memory–one hand here and the other here is how far? The firpins will be bolder than I and touch you where I have not. They will caress your body all day, as my lucky ambassador—lieutenant—proxy—and at unexpected, inconvenient times you will remember to feel their touch, which is my touch.”4

“Firpins” are not a historical undergarment. In fact, there is no record of the term aside from curious internet users’ queries about what the word used in Patience and Sarah refers to.5 The word was generated from the Ouija board—the session above includes the interaction: “Did you wear underpants? Yes. What did you call them? (We made no note and have forgotten the word she gave—something like Firpins.)” It seems clear that Alma used the Ouija sessions as an authoritative source on the details of early nineteenth-century New England living, as she used this detail, even despite noting that she may have recorded it incorrectly.

The Ouija sessions were not purely fact-finding missions. Alma began her notes on this session with a description of her emotional turmoil at the idea that Mary Ann was bored by the questions she was asking. She was emotionally invested in her relationship with Mary Ann and Florence. And, Betty was too.

Alma and Betty + Mary Ann and Florence

Alma was unable to operate the Ouija board without Betty, so the two conducted all of the sessions together. This frustrated Alma, as she could only contact Mary Ann and Florence if Betty was willing and had enough energy.6 However, together the two formed a strong connection with Alma’s historical inspirations.

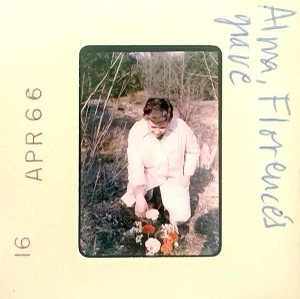

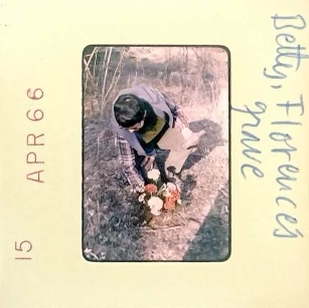

As part of their journey, Alma and Betty visited Brundage Hill, which they believed to be the site of Mary Ann and Florence’s farm. Just as Mary Ann had directed them to do in the very first Ouija session, photographs show that they visited Florence’s grave—and brought flowers with them. Mary Ann and Florence became more than elusive historical figures and more than an unusual spiritual connection: Alma and Betty were strongly attached to the relationship they had created together with Mary Ann and Florence.

Patience and Sarah’s happy ending was groundbreaking in the history of lesbian literature. Its possibility was important to lesbian women, used to stories from the mid-twentieth century in which lesbians were punished in the end.7 Alma’s alternative method of imagining allowed her to construct this story of an optimistic queer past, a past that the historical record had neglected. As Alma concluded in the afterword to the novel, “We are provoked to tender dreams by a hint. Any stone from their hill is a crystal ball.”8

Think About This

Why have some histories been recorded while others have not? Whose stories have not been preserved in the historical record?

Do we still have the same need for optimistic queer literature today? For the same or different reasons that queer people needed it when Alma was writing?

Who would you talk to using the Ouija board? Whose story needs to be told today?

Further Reading

Kumbier, Alana. “Inventing History: The Watermelon Woman and Archive Activism.” In Ephemeral Material: Queering the Archive, 51-73. Sacramento: Litwin Books, 2014.

In this chapter, Kumbier discusses Cheryl Dunye’s film The Watermelon Woman, focusing on Dunye’s use of alternative forms of historical evidence to counteract a lack of information about marginalized groups in the historical record. Kumbier examines the power archives and libraries have in deciding what histories are preserved and accessible, and how alternative or counter-histories might be used to combat those systems. It is useful to consider Routsong’s work on Patience and Sarah alongside Dunye’s work on The Watermelon Woman to think about how they creatively imagined pasts that were not recorded.

Wavle, Elizabeth M. “Isabel Miller, pseud. (1924- ).” In Contemporary Lesbian Writers of the United States: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, edited by Sandra Pollack and Denise D. Knight, 354-360. 1993.

This entry provides brief biographical information on Routsong, including her childhood, marriage and children, and writing career. It also includes an overview of her major works and responses to her work. Wavle reads Patience and Sarah as resistance against the idea of lesbianism as “a sickness or deviance.” There has been no extensive writing on Routsong’s biography, but this source is a helpful overview for understanding the trajectory of her life.

Zimmerman, Bonnie. The Safe Sea of Women: Lesbian Fiction 1969-1989. Boston: Beacon Press, 1990.

Zimmerman narrates a story about lesbian literary history beginning in 1969, the year that Routsong first self-published Patience and Sarah as A Place for Us. Scholarship on twentieth-century lesbian literature often places Patience and Sarah at a turning point when lesbian literature began to provide hopeful endings. Zimmerman positions Routsong as the author who began creating, “a literature that expressed the new truths and visions we were creating for ourselves” in the 1960s and 1970s, as opposed to the “dreary portrayals of self-hating ‘inverts’” (like The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall) that were common in the early 1970s (xi).

Further Research

For Alma and Betty’s published reflections on the writing process for Patience and Sarah, see:

Deran, Elisabeth. “Patience & Sarah Come to Life.” Patience and Sarah, 207-214. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2005.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. “1962-1972: Alma Routsong, Writing and Publishing Patience and Sarah, ‘I Felt I Had Found My People.’” In Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.: A Documentary, 433-443. Meridian, 1992.

Archival Collections

Isabel Miller papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections

Elisabeth Deran papers, University of Delaware Special Collections

Footnotes

Header image: Patience and Sarah draft sketch. Isabel Miller papers, Box 11, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00572, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts,

- Ouija notes. Isabel Miller papers, Box 21, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00572, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- Jonathan Ned Katz, “1962-1972: Alma Routsong, Writing and Publishing Patience and Sarah, ‘I Felt I Had Found My People,’” in Gay American History : Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.: A Documentary, (Meridian, 1992), 434. Originally published 1976. ↩︎

- Folder of research on Mary Ann Willson. Isabel Miller papers, Box 5. ↩︎

- Isabel Miller, Patience and Sarah, (Fawcett Crest, 1972), p. 107. ↩︎

- baronnessv (screen name), “Costume Question, Forwarded for a Friend,” LiveJournal, October 6, 2009, baronessv.livejournal.com/463519.html. ↩︎

- Ouija notes, Oct.31, after supper. Isabel Miller papers, Box 21. ↩︎

- Bonnie Zimmerman, The Safe Sea of Women: Lesbian Fiction 1969-1989, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990), xi. ↩︎

- Miller, Patience and Sarah, p. 192. ↩︎