The 1929 Stock Market crash sparked economic catastrophe, panic, and despair across the United States and around the world. Children felt these effects acutely, as their unemployed parents often struggled to keep the family afloat. Many had to take on additional responsibilities and adapt to the challenges of the Depression.

This moment also shaped children’s lives in two unexpected ways: it increased school attendance rates and put pressure on children to participate in mass culture and consumerism.

High unemployment and a changing economy requiring increased training for more kinds of positions combined to cause more teenagers, who might have otherwise dropped out to start working, to stay in school longer. Additionally, stores, desperate to make money in a depressed economy, ramped up advertising and targeted children as a consumer base. The result was that attending school became an experience shared by most children, and schools became a place where young people felt the pressures of both conformity and consumerism.

Working-class children often felt pressure to conform to the social standards established by their middle-class peers. Children who wore clothing that clearly marked them as a “relief kid,” meaning their family received governmental aid and one or both parents were out of work, often felt embarrassed by this label. Some impoverished children felt isolated from their peers because of it.

“We also received clothing––baggy and gray mostly, some brown and black, and shoes, all looking like prison issue. These garments––sweaters, jeans, skirts, shirts, and stockings––were so distinctive that you were marked as a “relief kid” the minute you wore any of it to school. This was particularly mortifying to girls, but we boys didn’t care.”

– Tomás Ramirez, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, born 1926

The kind of grey clothing described by Ramirez. The child who wore these overalls was likely 4-6 years old, while Ramirez was a few years older at the moment he describes. Notice the patching and repeated repair on the seat of the pants.

“I remember my senior year in high school, 1932. I had two pairs of overalls. I had one with patches on it and I had one that didn’t have patches on it. That was the good one. You wore that to school; you changed immediately when you came home and put on the pair with the patches.”

– John Godwin, Pembroke, North Carolina, born 1915

Kids acutely perceived the clothing worn by their classmates and the social status it implied. Certain clothing items carried particular weight. Overalls indicated working-class status, while knickers (baggy pants that cinched just below the knee) signaled wealth.

“Knickers were a big deal then, and most of the rich boys had them. Plaid-patterned stockings were, of course, de rigeur––they were transformed into pint-sized Ben Hogans. It was just as well that we couldn’t afford them; our amputee stockings would’ve looked awful with knickers. I remember wearing bib overalls––no style sense––until eighth grade. They covered a multitude of sins.”

– Tomás Ramirez, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, born 1926

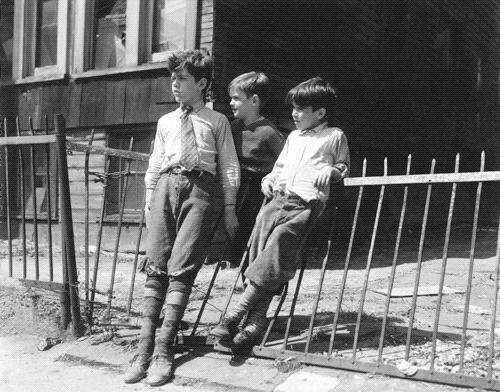

These 9 or 10-year-old New York City boys have just left school. Notice that the leftmost boy is wearing the plaid-patterned stockings described by Ramirez, and all three are wearing knickers. Their outfits indicate their family’s class status.

Kids often could tell where their classmates’ clothing came from. For some children more than others, this aspect of their clothing carried significant social weight. Working-class kids often received “relief issue” clothing or hand-me-downs from friends and neighbors.

“As for clothes, except for shoes, they were the last thing Mother thought of spending money on. Mostly we depended on hand-me-downs. In the girls’ fiction I read, the less well-off children and youth resented clothes from rich relatives or “the missionary barrel.” Even Mary Elizabeth, who probably suffered more than Caroline and I did from not having store-bought clothes, liked clothes given to us by people that we liked. I remember feeling almost glamorous in dresses that my Expression teacher gave me and those of Lousie Adams, “Miss McKenzie” year after year in the town’s beauty pageant.”

– U.T. Miller Summers, McKenzie, Tennessee, born 1920

While the mothers of working-class children were busy with work outside of the home and often didn’t own sewing machines, middle-class children wore primarily homemade clothing. Mothers and older sisters sewed clothing for the whole family. The fabric for these garments often came from store-bought bolts of fabric.

“Momma bought two bolts of cloth each year for winter and summer clothes. She made my school dresses, underslips, bloomers, handkerchiefs, Bailey’s shirts, shorts, her aprons, house dresses and waists from the rolls shipped to Stamps by Sears and Roebuck.”

– Maya Angelou (née Marguerite Johnson), Stamps, Arkansas, born 1928

Especially as the depression set in and tightened family budgets, women turned to the cotton sacks that flour, oats, and animal feed were sold in to replace store-bought fabric. Once companies realized that people were making clothing out of their packaging, they started producing these bags in fashionable prints and colors to appeal to consumers and their determination to repurpose and make do.

This dress, likely worn by an 6- to 8-year-old girl, is made of cotton fabric that may have come from a feed or grain sack. Its bright print contrasts sharply with the drab colors of the “relief”-issue clothing and it remains in very good condition.

The tie-back and apron style to this 1930s dress indicate that it was likely worn by a girl who lived on a farm or in a rural area. It may have been made either from a bolt or sack fabric, but it was worn very little and is in perfect condition.

“Bunny remained my best friend of all…. Her mother, like mine, made her clothes, and in second grade we had twin sailor dresses with white stars and braids on the collar.”

– June Pair Kilpatrick, Edgarton, Virginia, born 1932

Girls’ dresses in this era were short. The above-the-knee style was modeled after the dresses worn by famous child star Shirley Temple, whose influence was nearly ubiquitous. Movies shaped how this generation saw themselves and the world around them.

“Movies, in spite of the times, were affordable to nearly everyone, no matter how poor. Shirley Temple, whom I both adored and envied, was only a year older than I. She became my first heroine.”

– June Pair Kilpatrick, Edgarton, Virginia, born 1932

“All the girls in second grade at St. Boniface School idolize Shirley. She’s the model of goodness and beauty in days filled with bad things happening in our city and in the world. I save my pennies so I can go to these Saturday matinees as many times as I can. My heart gets jiggly as I watch Shirley dance across the big screen, her shiny curls bouncing, ruled dresses twirling, and her dimpled smile meant just for me.”

– Ludmilla Bollow (née Rosik), Manitowoc, Wisconsin, born 1926

Children whose families could afford it bought factory-made, ready-to-wear clothing from stores. This clothing was often seen as more elegant or “sophisticated” than homemade clothing.

“My Arizona uncle had sent me five dollars, which I spent on the sunburst pleated skirt in practical navy blue, the first new ready-made skirt I had ever owned. I enjoyed riding my bicycle in my sunburst pleated skirt past Ulysses S. Grant High School to Fernwood.”

– Beverly Cleary (née Bunn), Portland, Oregon, born 1916

“The dress I wore my first day in seventh grade in McKenzie was sure to be good for conversation. It was made from the shiny yellow material called Peter Pan on which I had embroidered a hoop-skirted lady in a lower garden when I was in fourth grade, and it couldn’t have been more different from the neat white-collared blouse and pleated skirt that Lloyd Allison wore. A Shaeffer fountain pen on a black ribbon hung around her neck. . . . As I accepted Lloyd’s paper, I thought that if Annie Fellows Johnston, or any other children’s author, were to walk into the room, she would choose Lloyd, the prettiest and best-dressed girl in the room, to be the heroine.”

– U.T. Miller Summers, McKenzie, Tennesse, born 1920

A factory-produced shirt for a 4-year-old boy. This shirt was never sold and is in new condition today.

Many teenagers and adolescents worked part-time to save up money to buy the clothes and makeup they felt would earn them social status or security at school.

“In our neighborhood, no girl would dream of entering high school in half socks. I used hoarded nickels and dimes to buy silk stockings.”

“I detoured from my usual route to buy, with twenty-five cents saved a nickel at a time, a pair of red bobby socks at Woolworth’s. Mother made me return them on my next trip overtown. Risking mother’s disapproval of lipstick on young girls, I bought a tube of Tangee lipstick at the dime store and applied it the minute I got home from the orthodontist.“

– Beverly Cleary (née Bunn), Portland, Oregon, born 1916

“I was thrilled to be earning four dollars a week. I now had my own money to buy such luxuries as Tangee Lipstick, hair set gel, an extra pair of shoes––and Kotex sanitary napkins. In those days one could buy a very nice sweater for seventy-five cents.”

– Mildred Armstrong Kalish, Monroe Township, Iowa, born 1922

Wearing lipstick was an important signal of adulthood and independence for teenage girls in the 1930s. The high school social world saw wearing lipstick as an announcement of being “dateable,” and a signifier that they and their parents were on board with the dating and dancing that characterized modern adolescence. Girls whose parents did not approve, or who could not afford lipstick or did not desire to wear it, faced social exclusion.

“I never found my place among either boys or girls during the high school years. My hair remained straight, slicked back behind my ears. I did not even begin wearing pinky orange Tangee lipstick until I was a junior. I was notoriously bookish. . . . With my reputation for studiousness, not dancing, not wearing makeup and not dating, I had no hope of enticing any boyfriend, so I kept quiet.”

– U.T. Miller Summers, McKenzie, Tennessee, born 1920

Tangee lipstick was famous in the 1930s for “matching all skin tones,” and was the brand of choice for many teenage girls.

These teenagers often felt disappointment when their purchases did not give them the status they’d hoped for.

“With a bank account and clothes that I had bought for myself, I was sure that I had learned and earned the magic formula which would make me a part of the gay life my contemporaries led. Not a bit of it. Within weeks, I realized that my schoolmates and I were on paths moving diametrically away from each other.”

– Maya Angelou (née Marguerite Johnson), Stamps, Arkansas, born 1928

1930s children’s everyday lives were highly shaped by the social and political forces around them. They learned their parents’ prejudices, insecurities, and the nativist, racist, status quo and applied it to their peers in the classroom. The forces that became a norm of childhood in the 1930s continue to shape children today. Roughly 94% of U.S. kids attend public and private schools and mass media and culture shape kids lives more than ever before. Kids continue to feel consumerist pressures from their peers and face eduction systems that reproduce social inequality.

Reading these anecdotes, what stories resonated with you? Do any of the narratives evoke particular memories? Feel free to share them on one of the notecards on the desk.

What surprised you about the clothes themselves? Do you notice any motifs or patterns? What does this say about politics in 1930s America?

Further reading:

Lindenmeyer, Kriste. The Greatest Generation Grows up: American Childhood in the 1930s. American Childhoods. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2005.

This book offers a foundational introduction to childhood in the Depression-era United States. Lindenmeyer explains the issues faced by 1930s children and the way economic collapse affected children of different demographic groups differently. She pays particular attention to how school became the normative experience of childhood during the 1930s, and the role of popular culture and consumerism.

Matsumoto, Valerie J. City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles, 1920 – 1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Valerie Matsumoto’s overview of life for Japanese-American teenage girls during the 1930s and 1940s provides valuable context for the clothing I have on display and the experiences of Japanese-American oral history narrators. Matsumoto’s research seeks to analyze spaces of “ethnocultural peer association in which girls could claim modern femininity and American status while continuing to serve their families and communities.” Since clothing choices were an integral part of both “modern femininity” and “American status,” this book is an excellent next step for understanding how urban Nisei, or second-generation Japanese immigrants, navigated school and adolescence.

Pomerantz, Shauna. “‘Did You See What She Was Wearing?’ The Power and Politics of Schoolgirl Style.” In Girlhood: Redefining the Limits, edited by Yasmin Jiwani, Claudia Mitchell, and Candis Steenbergen. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2006.

For readers looking to understand childhood conceptions of clothing and social status at school outside of the 1930s, this chapter is a great place to start. Pomerantz offers her findings from an ethnographic study on teenage girls, clothing choices, and social status that she conducted in a Canadian High School in the early 2000s. She works to understand how “resistance is often expressed through the language of style” and the relationship between style and girls’ identity construction.

Scheiner, Georganne. “The Deanna Durbin Devotees: Fan Clubs and Spectatorship.” In Generations of Youth: Youth Cultures and History in Twentieth-Century America, edited by Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard. New York London: New York University Press, 1998.

This chapter offers an analysis of the ways increasingly prevalent movie and film culture shaped the self-perception and fashion choices of adolescent girls in the 1930s. This provides important context for trends of the time and how children responded to broader cultural influences, as girls may have sought to dress like their favorite movie stars, or admired female classmates who did.

Sources for quotes:

Angelou, Maya. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. A Bantam Book. New York: Bantam Books, 1969.

Bollow, Ludmilla. Lulu’s Christmas Story: A True Story of Faith and Hope During the Great Depression. New York: Titletown Publishing, 2014.

Cleary, Beverly. A Girl from Yamhill: A Memoir. New York, NY: Morrow, 1988.

Godwin, John. Interview by Renate Dahlin. 27 June 1984. Transcript. Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Kalish, Mildred Armstrong. Little Heathens: Hard Times and High Spirits on an Iowa Farm during the Great Depression. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2007.

Kilpatrick, June Pair. Wasps in the Bedroom, Butter in the Well: Growing up during the Great Depression: A Memoir. Portland, OR: Inkwater Press, 2012.

Ramirez, Thomas P. That Wonderful Mexican Band: A Memoir of the Great Depression. Fond du Lac, WI: T.P. Ramirez, 2017.

Summers, U.T. Miller. Hold tight, Sweetheart: A Memoir of the Twenties and the Great Depression. 2007.

Archival repositories and oral history projects with more narratives of 1930s childhood for continued reading:

Documenting the American South, Oral Histories of the American South, Southern Oral History Program, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (Oral histories of American Southerners)

Hanashi Oral History Collection, Go For Broke National Education Center. (Oral histories with Japanese-American World War II veterans)

HistoryMakers Digital Archive, Carnegie Mellon University. (Oral histories of Black Americans)

Houston Asian American Archives, Woodson Research Center, Rice University. (Oral histories of Asian Americans, particularly concentrated in the South)

Mexican-American Oral History Project, Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society. (Oral histories of Mexican-American residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul)

The Vermilion Lake People: Vermilion Lake Bois Forte Oral History Project, Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society. (Oral histories of Ojibwe residents of Bois Forte Reservation in Minnesota)