Creator’s note: this project is rooted in my firm belief in reproductive justice, which asserts the fundamental human right of every individual to lead autonomous, pleasurable, and resourced reproductive lives. Realizing a reproductive justice future cannot happen unless we confront the long history and present of reproductive injustices, and I believe this work is especially critical at a historically women’s college.

On February 24th, 2024, Haynes House officially received its new name. Originally named for zoology professors H. H. Wilder and Inez Whipple Wilder, concerns were raised about the problematic legacy of the Wilders due to their involvement in eugenics and excavation of Native American human remains.1

Though this was an important step towards reckoning with issues of racism and other forms of oppression throughout the institution’s history, Smith College’s eugenic legacy goes well beyond the Wilders.

The process of unearthing, mapping, and thus fully acknowledging Smith’s investment in eugenics has only just begun, revealing the foundational role of academia in creating and spreading eugenic ideology, the consequences of which endure to this day.

Exterior of College Hall from Elm Street, 1905-1919. Photographer unknown. College Archives Image Gallery.

Origins and Evolution of American Eugenics

The American eugenics movement was born out of a desire to “scientifically” prove racial hierarchy, and was based on the unfounded racist theories of elite European men dating back to the 15th century, coincidentally when justifications were needed to legitimize colonization and the institution of slavery.

click to read more

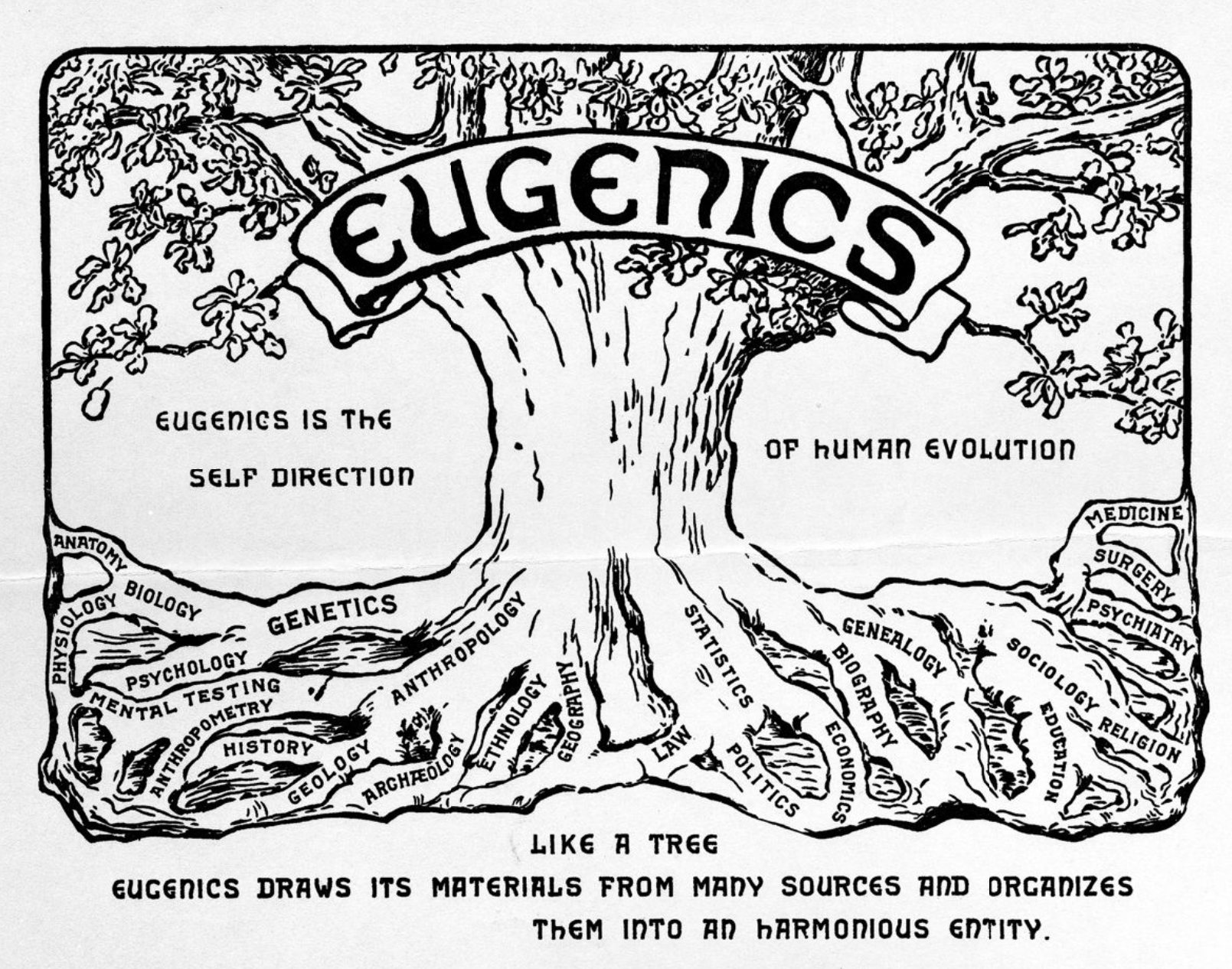

Eugenics, formally coined by Francis Galton (1822–1911), the cousin of Charles Darwin, gained scientific credibility through the influence of Social Darwinism and the rediscovery of Mendelian genetics, which reinforced its claim of a strict biological determinist view of human behavior. This ideological foundation sparked an insidious movement in the United States that has shaped immigration and sterilization policies, inspired the horrific actions of Nazi Germany, and even influenced progressive causes like birth control and environmentalism. Despite its far-reaching impact, the American eugenics movement was originally driven by a small circle of elite white men who believed it was their responsibility to influence the nation’s reproductive future and prevent what they saw as the racial decay and degeneration which threatened the future of white supremacy.2

Broadside of the Eugenics Tree, undated. Eugenics Record Office Records, American Philosophical Society

By the beginning of the 20th century, the American eugenics movement was in full force, implementing strategies to fund eugenic research, influence public policy, and disseminate eugenic ideologies into the public consciousness, primarily through educational initiatives.

Holding the reigns was biologist and Harvard graduate Charles Davenport, who, along with his cronies, founded the three main eugenics organizations in the US: the Eugenics Records Office (ERO), the Eugenics Research Association (ERA), and the American Eugenics Society (AES). Along with ardently racist, ableist, and classist eugenicists Madison Grant, H. H. Goddard and Harry Laughlin, Smith College zoology professor H. H. Wilder and his replacement, physical anthropologist Morris Steggerda, were staunch supporters of Davenport’s eugenic mission and active in the ERO.3

Though the racial pseudoscience of “mainline” eugenics eventually fell into public disfavor with the acceptance of the Boasian cultural paradigm by the 1930s and the horrors of Hitlerism which followed, the movement and its influence were far from over. With much important overlap, a new wave of eugenicists entered the scene during the 1920s, replacing their mainline predecessors and essentially rebranding eugenics to fit with the changing times. Among these “reform” eugenicists, who do not fit with our modern understanding of eugenicists as “political conservatives, [open] racists, and opponents of true democracy,”4 was sociologist Frank Hamilton Hankins.

A “Progressive” Eugenicist?

Frank Hamilton Hankins (1877-1970) was a prominent and influential sociologist, known for serving as the 28th president of the American Sociological Association. While he is remembered for his dedication to empirical science, advocacy for individual democratic rights, support of birth control, and critique of Nordicism, his deep involvement in the eugenics movement undermines this “progressive” legacy.5

“While we are denying the extravagant claims of the Nordicists, we also deny the equally perverse and doctrinaire contentions of the race egalitarians. There is no respect, apparently, in which races are equal; but their differences must be thought of in terms of relative frequencies, and not as absolute differences in kind. They are like the differences between classes in the same population. It thus appears that the eugenic contentions are fundamentally sound, as against both the racialists on one extreme and the thorough environmentalists on the other.”6

Frank H. Hankins, The Racial Basis of Civilization, ix

click to read more

Although his book The Racial Basis of Civilization: A Critique of the Nordic Doctrine (which the Smith College finding aid calls a “ground-breaking study”7), is lauded as evidence of his anti-eugenics beliefs for its critique of Nordicism, disparaging Madison Grant’s foundational eugenic text The Passing of the Great Race, Hankins clearly does not reject eugenics and fundamentally upholds racial hierarchy, even as this becomes less apparent in his later work. While Hankins critiqued the notion of racial purity, he openly advocated for eugenic applications of birth control, selective reproduction, and the sterilization of the “unfit,” primarily for low-income and disabled individuals, and also supported eugenic immigration policies.

Hankins was actively involved in numerous eugenics organizations including the American Eugenics Society, the American Population Association, the Population Reference Bureau, the Euthanasia Society of America, and the American Birth Control League (later renamed Planned Parenthood), among others. His eugenic activities outside of Smith College were extensive and continued beyond the expiration of eugenics’ scientific validity. Hankins’ papers provide important insight into how the eugenics movement adapted to maintain a semblance of credibility, eventually even partially accepting the influence of environment on human behavior. Yet they maintained their fundamental claims that certain populations were “unfit” to reproduce, and posed a threat to the future of civilization.

Professor of Sociology, 1922-1946

Because the field of sociology was still developing, Hankins tended to combine it with statistics (influenced by Galton) and biology, the two primary fields within which eugenics was first theorized. As late as the 1940s he was teaching courses such as “Theories of Cultural Evolution: Role of race and environment in the development of civilization. Heredity and eugenics, education and environmental improvement” and “Problems of Population Quality: Human variability; roles of heredity and selection; social stratification; heredity versus environment in individual and racial differences; eugenics.”8

Beyond the eugenic content he explored within the classroom, Hankins’ engaged in practical experiences conducting eugenic fieldwork and research, enabled by his position at Smith College.

Hankins’ Eugenic Work at Smith

click on headings for details

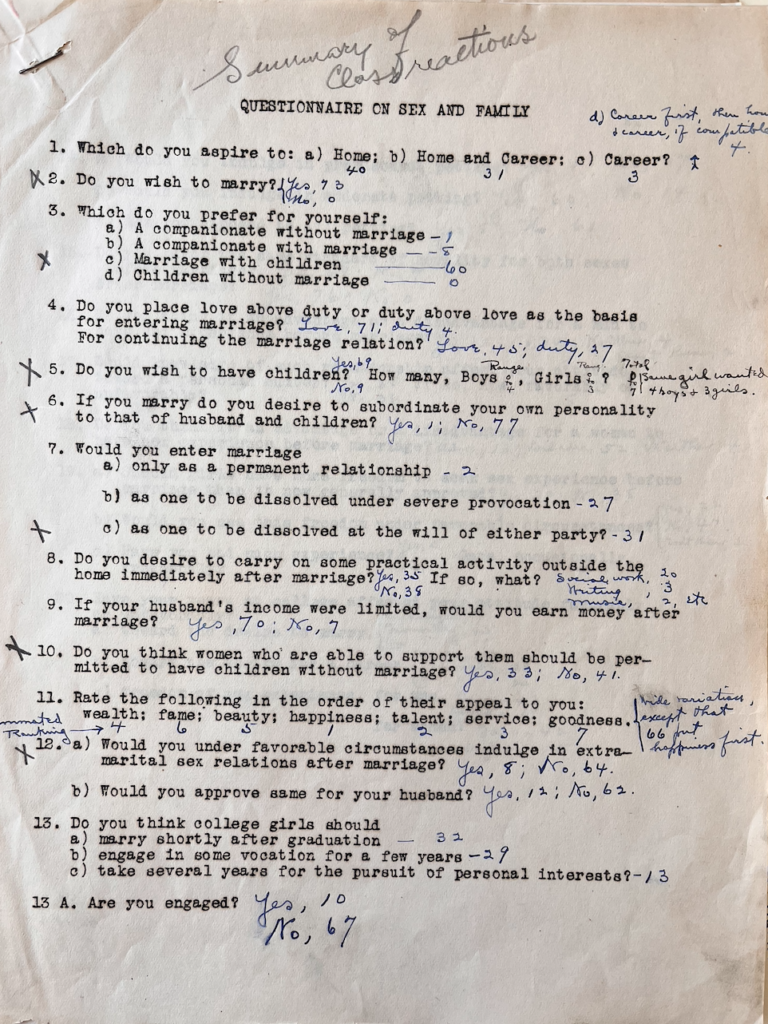

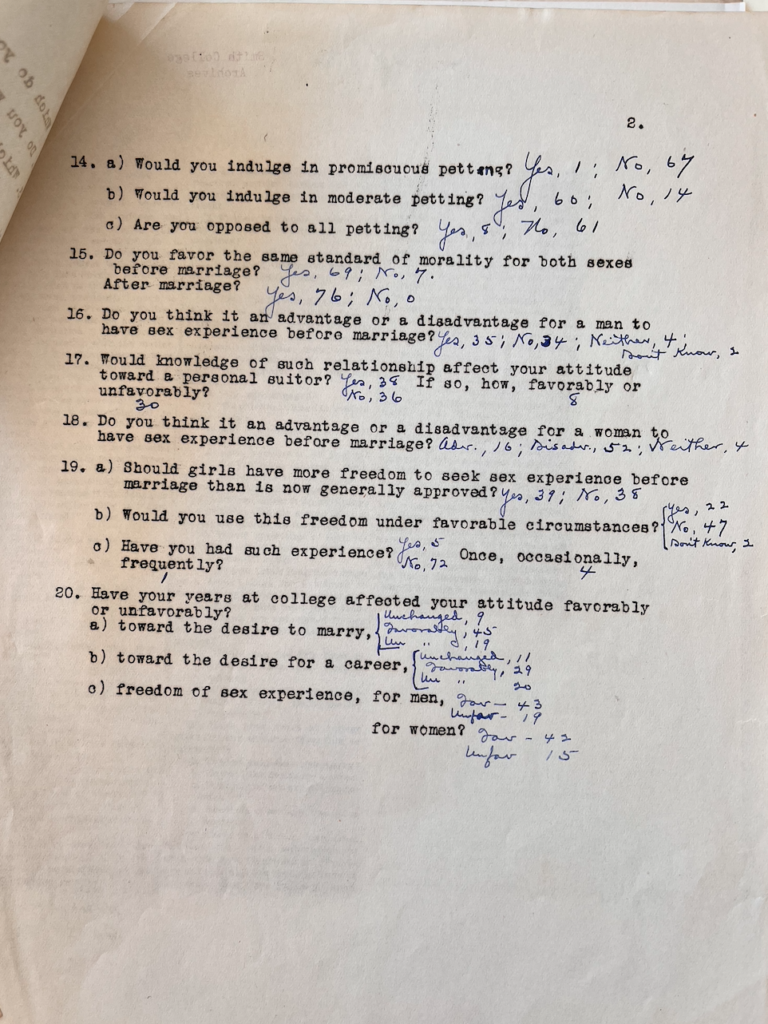

Sex Questionnaire, 1925

In 1925, Professor Hankins gave the students in his sociology seminar a questionnaire on sex and family. Because eugenicists viewed college students as the ideal reproducers of the nation, Smith students’ views on sex and family were undoubtedly a subject of great interest. Eugenicists feared that educating upper class white women might negatively affect their desire to make use of their “superior germplasms” and produce large families.9

The Shutesbury Project, 1928

In 1928, Leon Whitney, the secretary of the American Eugenics Society and dog breeder from Northampton, approached Professor Hankins with a project to study the genetic histories of nearby towns Leverett and Shutesbury. Hankins recruited his students, eager to gain experience doing field work, to unethically survey and perform mental tests on individuals in these rural and low income communities in an effort to prove their supposed genetic “degeneracy.” The study was fundamentally flawed both ethically and intellectually from the start, and contradicts Hankins’ reputation as an empirical scientist. This research informed Whitney’s book, Case for Sterilization, which advocated for negative eugenic policies and was praised by none other than Adolf Hitler.10

Sabbatical in Nazi Germany, 1936

Although various publications and his obituaries refer to Hankins’ sabbatical studying “on the scene, social conditions in Nazi Germany,”11 they omit the content of his research, which was undeniably eugenic in nature. While negative eugenics, the practice of discouraging or outright preventing certain populations from reproducing, positive eugenics focuses on encouraging the reproduction of “desirable” populations. This latter iteration of eugenics was the focus of Hankins’ study in Nazi Germany.

Birth Rate Study of Smith Alumnae, 1946

Given the eugenic fear of “race suicide,” eugenicists were deeply concerned with the birth rates of elite white college students. The Population Reference Bureau (PRB), of which Hankins was a part, organized a nation-wide study to determine whether students were having enough children to replace themselves. As the liaison between the PRB and Smith alum, Hankins conducted this research by sending out surveys to the classes of 1921 and 1936.

“Attention, Smith Wives! … Because of this favorable combination of heredity and environment, the sources of future nation-builders lie with us and those like us, the women graduates of America. Are we doing our part? The Population Reference Bureau says ‘No.’ … for the goal is to increase the percentage of our population consisting of intrinsically able people, and we, their mothers, are falling quite short of even replacing ourselves.”

Letter to Smith Alums from the Alumnae Association of Smith College, 1946. Frank Hamilton Hankins Papers, Smith College Archives.

The results of the study concerned Hankins and the PRB, and the though Alumnae Association of Smith College refrained from publicizing the results, they sent out a letter urging Smithies to have more babies.

Letter to Smith Alums from the Alumnae Association of Smith College, 1946. Frank Hamilton Hankins Papers, Smith College Archives.

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important to reckon with Smith’s eugenic past? What might be a meaningful and substantial way to do so?

- Where do we see the influence of eugenic ideology in our current time? What eugenic assumptions about reproduction have lingered in the public consciousness?

Further Reading

- Robert Wald Sussman’s book The Myth of Race provides a comprehensive overview of the history of eugenics and scientific racism, from its early philosophical origins, to the rise and fall of the American eugenics movement, to the persistence of eugenic ideology and modern scientific racism.

- Betsy Hartmann’s essay, “Population Control I: Birth of an Ideology,” traces the origins of population control theory to the eugenics movement, especially due to its significant influences on the birth control movement, which first gained traction due to its practical potential to curb the fertility of “undesirable” populations.

- Lorreta J. Ross and Rickie Solinger’s book Reproductive Justice: An Introduction is an essential and comprehensive overview of the reproductive justice movement. It is grounded in an intersectional analysis of race, class and gender politics throughout the history of reproductive injustice in the United States, which is of course intertwined with the eugenics movement.

Further Research

The Eugenics Archive provides several interactive tools to learn about eugenics including a comprehensive timeline, stories from survivors, and an interactive map of the web of ideas, events, and people connected to the history.

Yale’s anti-eugenics initiative, “Eugenics and Its Afterlives,” confronts the history of eugenics at Yale, which hosted the American Eugenics Society and provides resources to learn more about eugenics from a variety of disciplines and perspectives. This website provides an example of how an institution has reckoned with its involvement in eugenics.

Archival Collections

Frank Hamilton Hankins Papers, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00060, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Archivist reference files, CA-MS-01213. Smith College Archives.

Student papers and theses collection, College Archives, CA-MS-01113. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Works Cited

- John Macmillan, “Home Sweet Haynes,” Smith College News & Events, February 26, 2024, https://www.smith.edu/news-events/news/home-sweet-haynes ↩︎

- Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014). ↩︎

- Sussman, Myth of Race. ↩︎

- Simone Diender. The “Reasonable” Professor Hankins: Eugenics, Science and Women’s Education in the 1920s. 2007. Student papers and theses collection, College Archives, CA-MS-01113, Box 1. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- Charles H. Page, “Obituary of Frank H. Hankins,” The American Sociologist, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 288-289, https://www.asanet.org/frank-h-hankins/. Accessed March 26, 2025. ↩︎

- Frank H. Hankins, The Racial Basis of Civilization. A Critique of the Nordic Doctrine, Alfred A. Knopp, Inc., 1926. ↩︎

- Frank Hamilton Hankins Papers, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00060, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/resources/362, Accessed March 26, 2025. ↩︎

- Smith College Catalogue, Smith College, 1942. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/smithcata4243smit/page/n155/mode/2up?q=hankins, Accessed March 29, 2025. ↩︎

- Diender, The “Reasonable” Professor Hankins. ↩︎

- Diender, The “Reasonable” Professor Hankins. ↩︎

- Page, “Obituary.” ↩︎