Smith College prides itself on raising students who break the rules of society and build new rules for themself. Just this past year, the college endorsed this idea at its annual Rally Day, encouraging students to “Be Brave, Set High Goals, Break Barriers.”1 It’s an institution that praises activists and feminists and those who go on to pioneer new horizons, even if that means breaking the rules. But it is just that: an institution, with regulations and policies strongly enforced by Residence Life, the Conduct Board, and the Administration – something that stands in direct contradiction with its ideals for its students post-grad.

The Warden

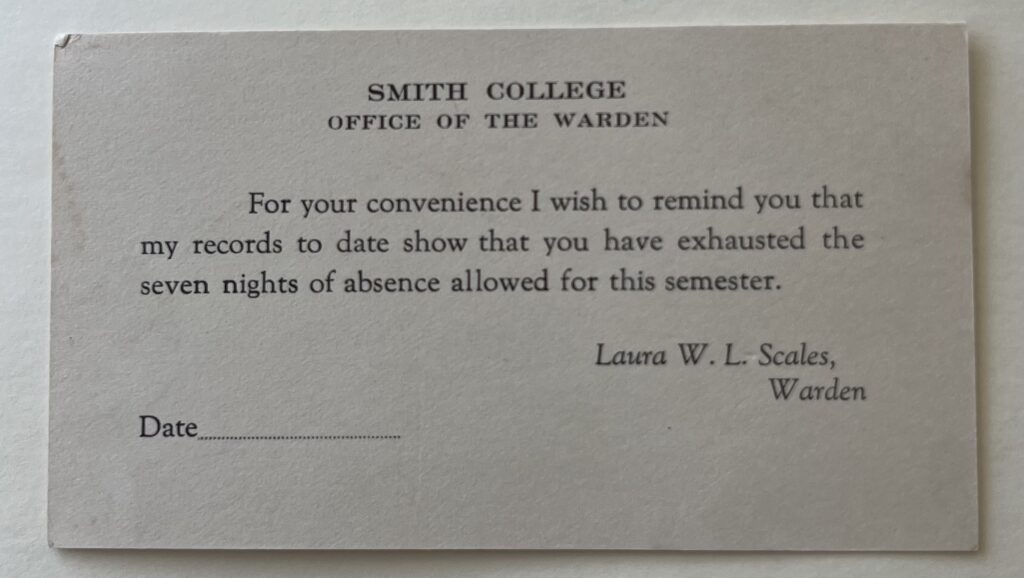

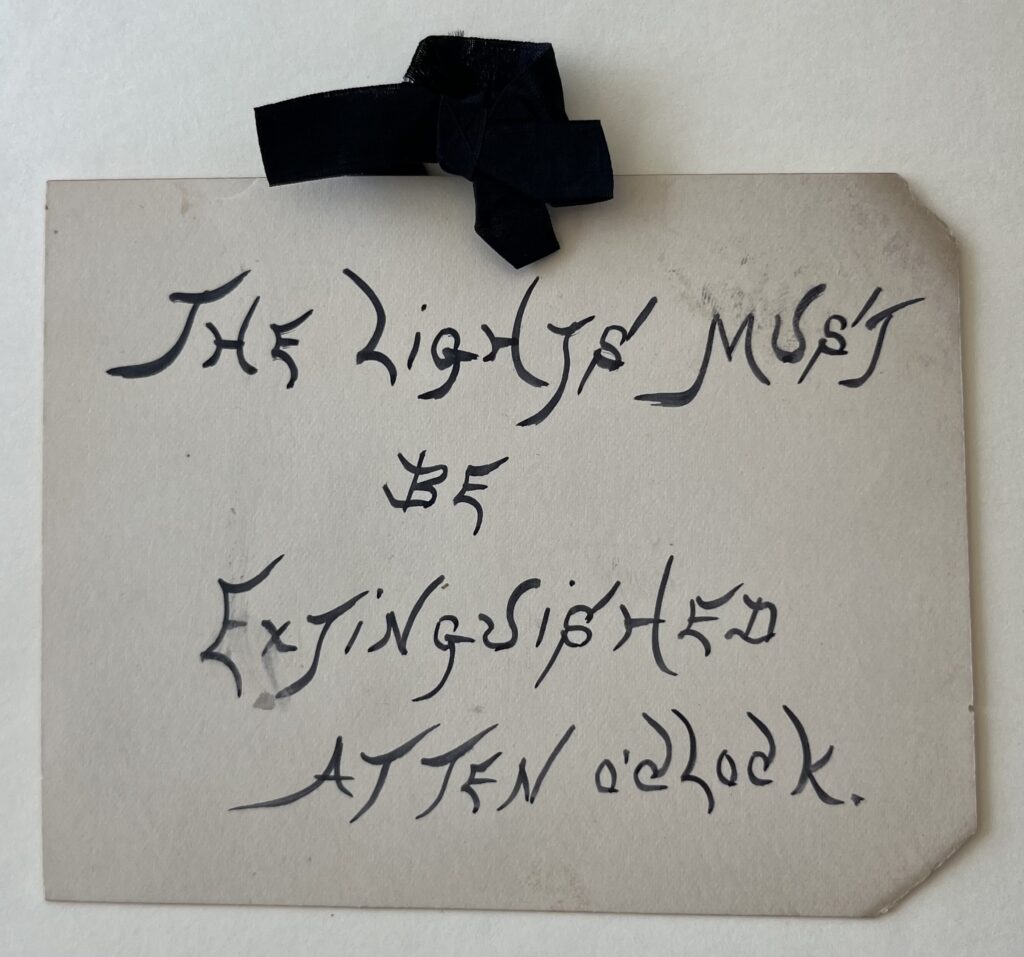

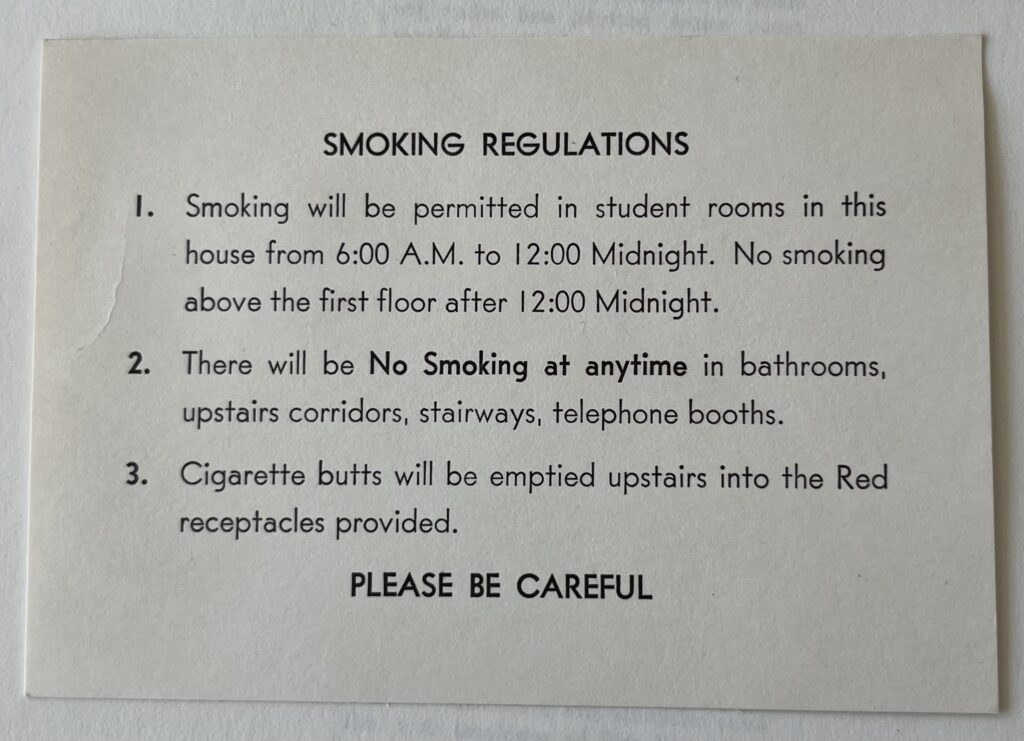

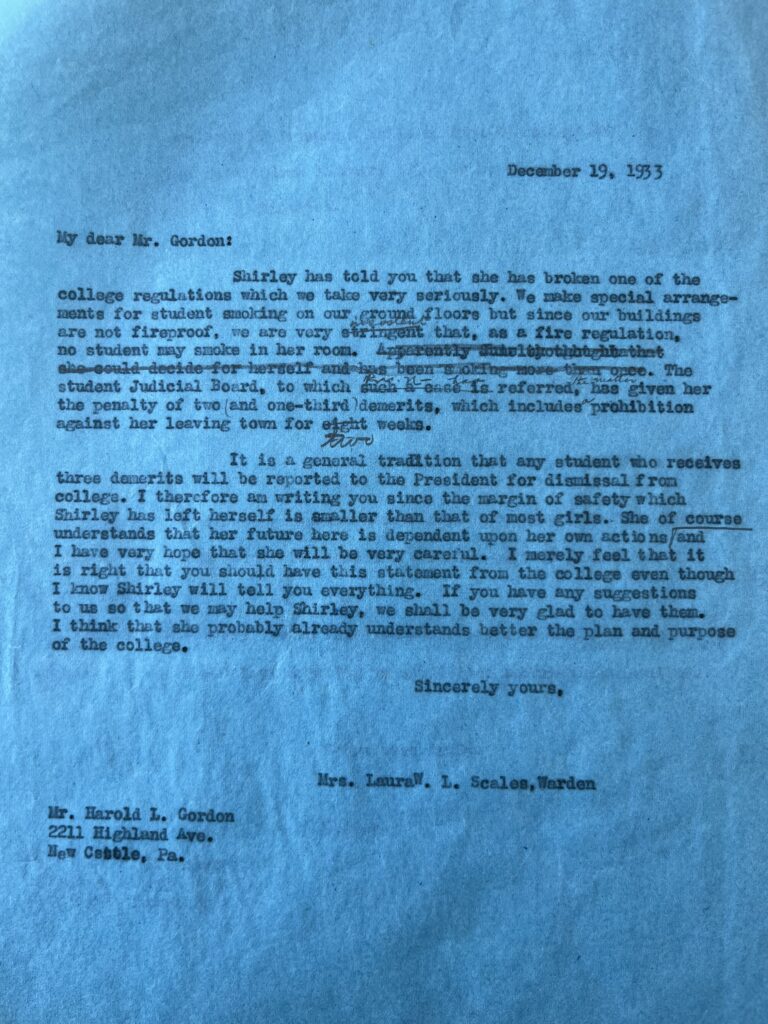

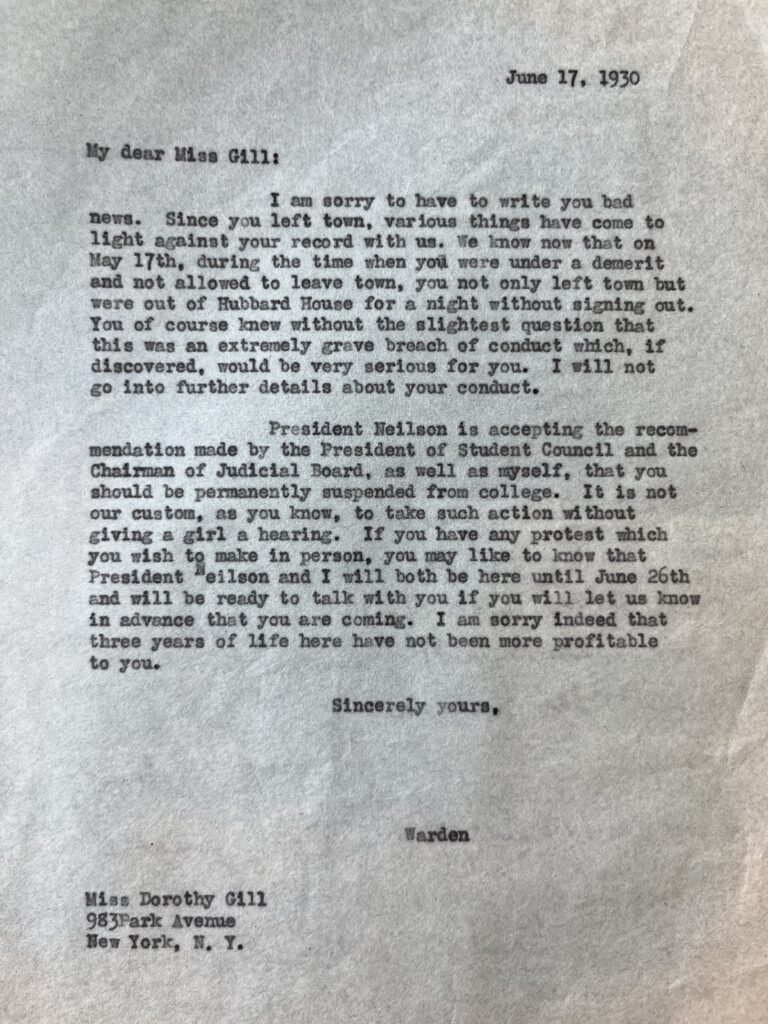

Before Smith had a Dean of Students, they had a Warden – a quite intense title for the faculty member overseeing the academic and personal success of Smith College students. The most prominent holder of this title is our very own Laura Scales, who served in the 1920s & 30s. Her main duties meant enforcing discipline across the college – just three demerits and Smith students would be expelled, or, sorry, politely asked to take a permanent suspension. 2 3

Shown here are a selection of letters from the Office of the Warden, in a folder titled Special Cases, but a more apt label is Expulsions. From smoking, to immoral behavior at parties, to missing curfew, there were a whole slew of rules that could end any Smithie’s college career:

What rules make sense? What are too harsh? What do these rules say about the moral standards Smith students – and women, more generally – were held to? What do current rules say about current moral standards? If you were a student in the 1930s, what would you have been expelled for?

Blight Girls

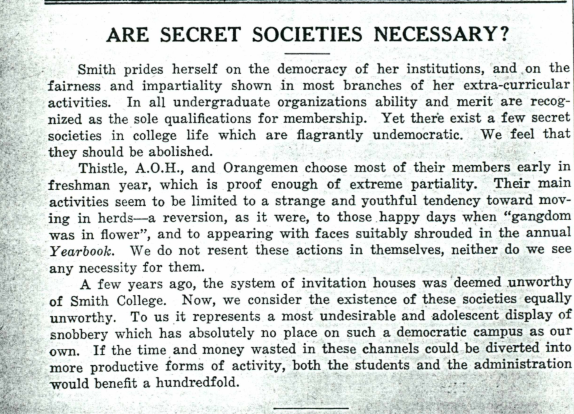

From the 1890s, until the late 1960s, Smith College had two rival secret societies: the Ancient Order of the Hibernians and the Orangemen.4 Both stem from pre-existing Irish religious groups, but became something entirely different here on campus.

While not entirely against the rules, the societies kicked up major controversy across campus – including multiple opinion pieces to campus publications, calling for their disbandment on the grounds of being “undemocratic.”

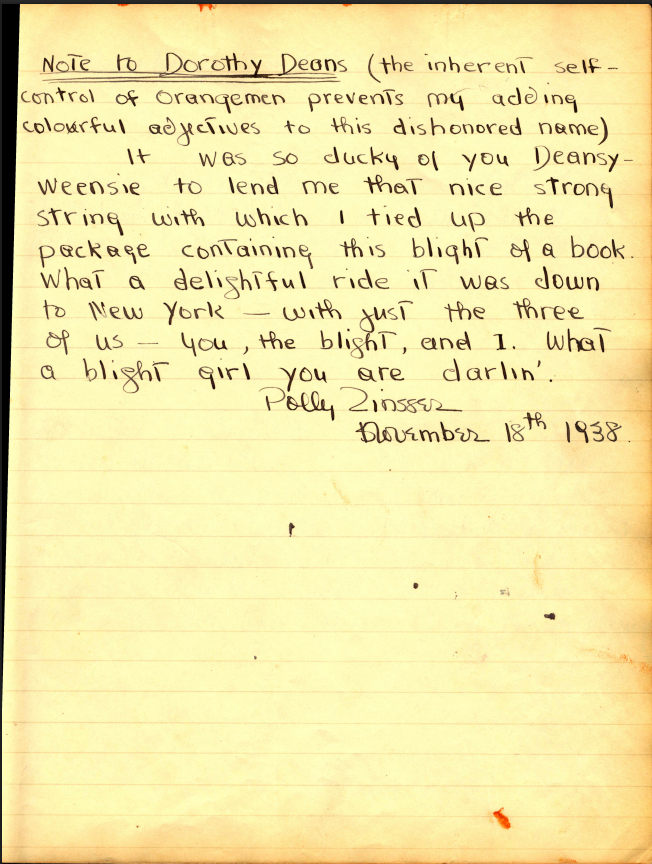

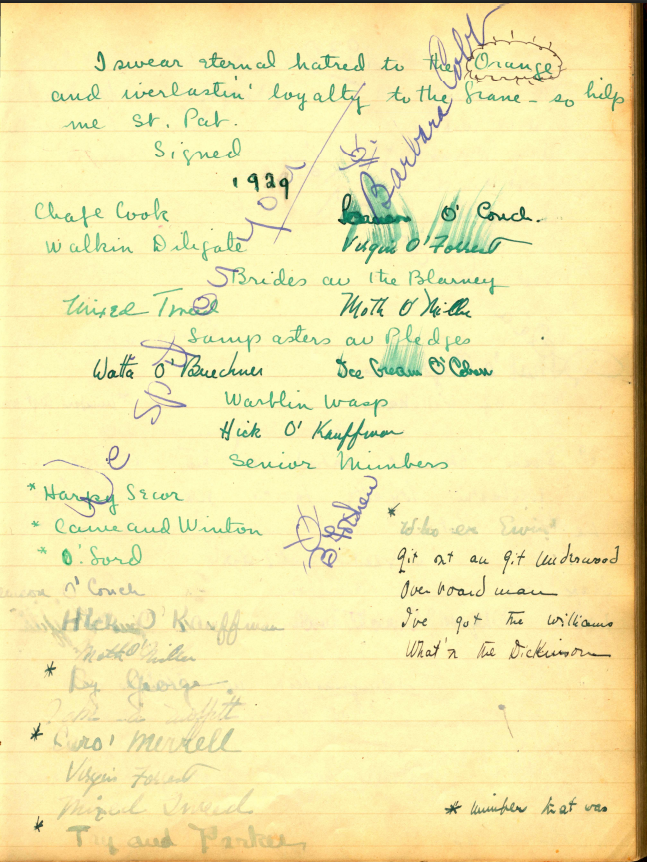

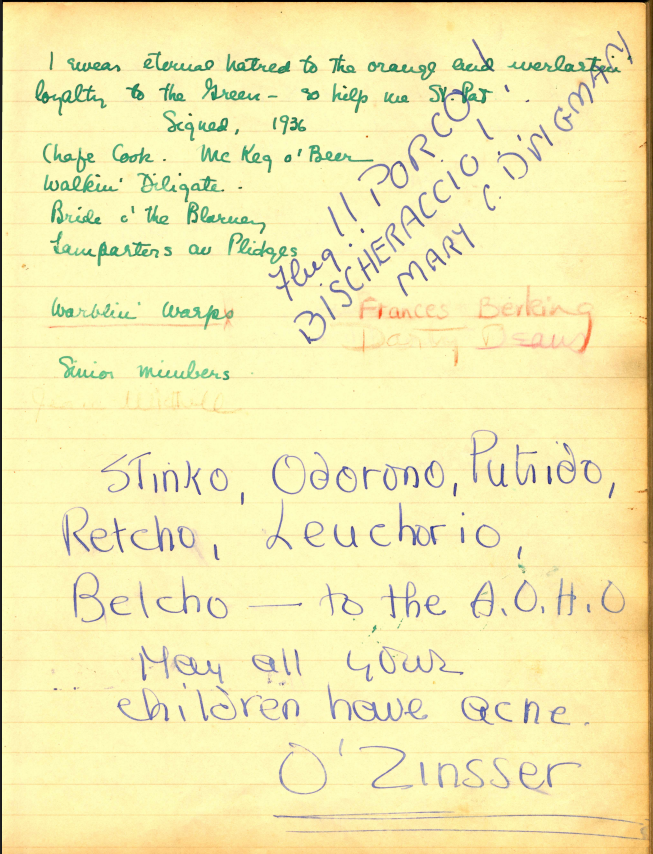

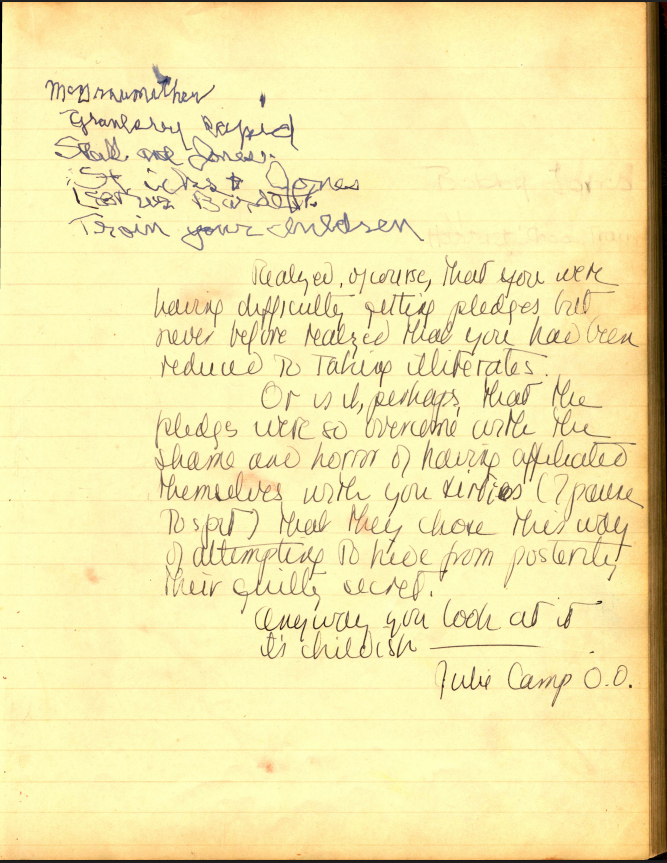

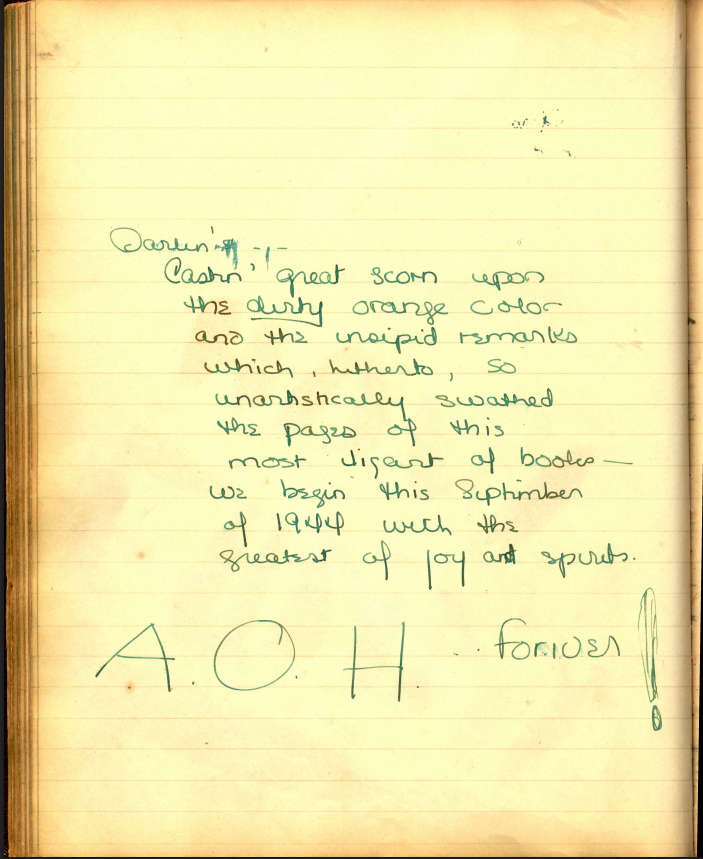

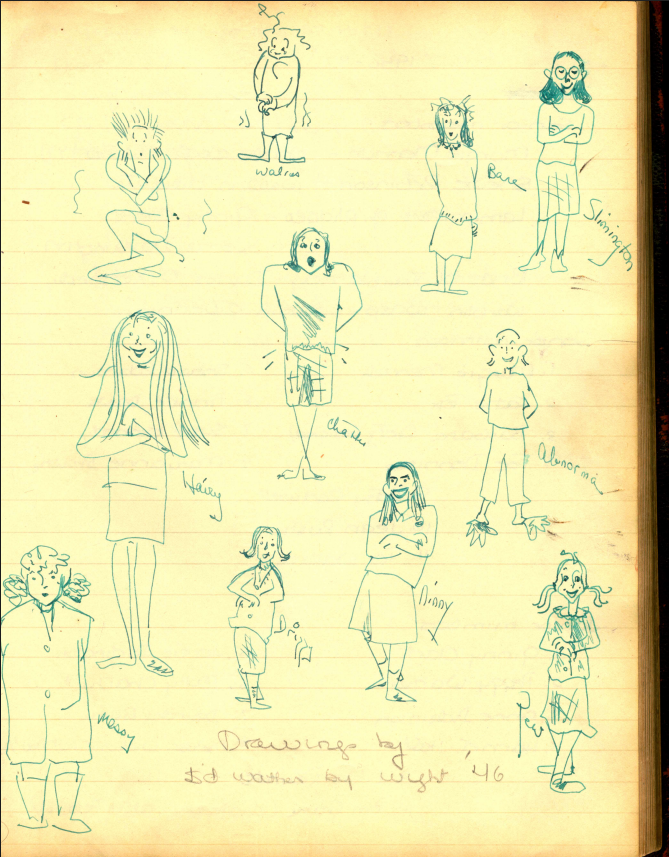

What did they do on campus? Mostly, they hated each other for seemingly no reason! And wrote mean things about each other in a scrapbook – think the Mean Girls Burn Book, circa 1938.5

Some of the most scathing quotes include these pages. Note the language they use – not always outwardly mean, but cutting in a sickly sweet, too polite, academic way:

Why do you think they were so mean to each other? What does this say about the way girls and women are allowed to be aggressive or fight?

The AOH and Orangemen were disbanded officially in 1948, but both clubs continued unofficially well into the late 60s. Now, they only exist in memory and in the archives, and in the questions they inspire.

What is the appeal of joining an exclusive group? Why do you think these secret societies were so attractive to Smith students? Should we bring secret societies back? If so, how would we have to restructure them to be more democratic?

Meant to Be Broken

Not all rules are meant to be followed – what happens when Smith students speak against the college, pull senior pranks, or throw unregistered parties, if all of these activities are against policy?

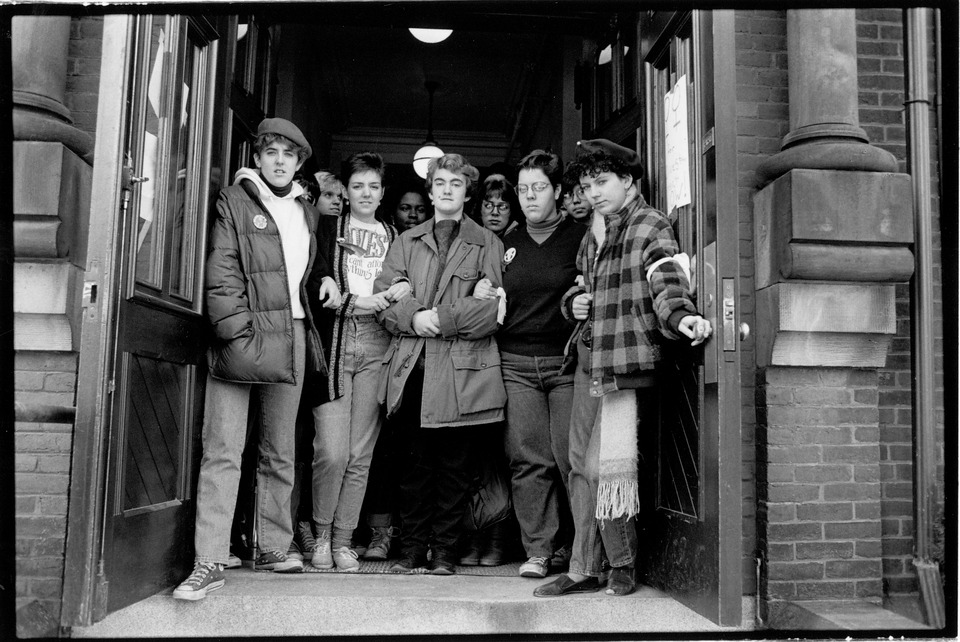

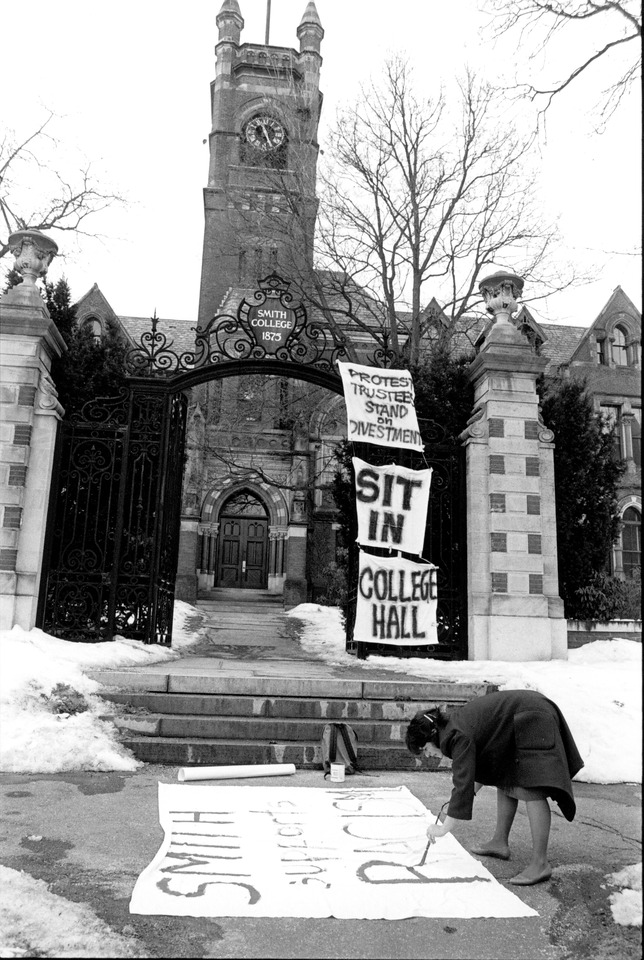

In 1986, around 200 students staged a sit-in at College Hall to protest the college’s investment in the South African apartheid.6 Smith has a long tradition of protests and demonstrations, stretching back to 1933,7 but this was by far the most prominent and public display, getting attention from the Hampshire Gazette and United Press International.8

The protest disrupted college operations and stood in violation of many policies.9 Yet in these photos – two of many documenting the event – the protesters show their faces proudly, identifying themselves as the perpetrators. They stand together in solidarity – a collective rule breaking.

Should protests be against the rules? When is it necessary to break rules?

Recommended Reading

Lee, Mabel Barbee. “Censoring the Conduct of College Women.” The Atlantic, April 1, 1930. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1930/04/censoring-the-conduct-of-college-women/305844/.

This newspaper article from the 1930s brings in an outside perspective on how college women were perceived as well as the growing youth culture and shifts in morality of this time period. It is in direct conversation with the archival materials, but offers a different external perspective that gives context to the society surrounding Smith College and its policies in the early 20th century.

Nikolaidis, A. C., and Winstron C. Thompson. “Breaking School Rules: The Permissibility of Student Noncompliance in an Unjust Educational System.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 91, 2021, pp. 204–26.

Nikolaidis and Thompson’s writings discuss the sociological tendency to break rules and how rules are treated when they are perceived as unjust or unfair. This valuable insight will supplement the archival materials to understand why certain rules are more likely to be broken and whether or not they are ethical despite their status as policy.

Simmons, Rachel. “Introduction.” Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls. Harcourt, 2003.

A contemporary of Queen Bees and Wannabes (Tina Fey’s inspiration for Mean Girls), Simmons’ book explores aggression and bullying in teenage girls, the underhanded ways in which they fight and the need for that aggression – and how it differs from the moral standards fighting between boys is granted. While Simmons’ research focuses on middle and high school students in the early 2000s, the same methods and theories she draws on can apply to the secret societies at Smith, giving us a psychological and sociological perspective to this history.

Bibliography

Archival Materials

Absence Card, 1930s. Social Regulations, Administrative Office Records, Box 578, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01005, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Curfew Reminder, 1920s. Social Regulations, Administrative Office Records, Box 579, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01005, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smoking Regulations, 1920s. Social Regulations, Administrative Office Records, Box 579, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01005, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Shirley Gordon, 1933. Special Cases, Office of Student Affairs Records, Box 58, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01055, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Dorothy Gill, 1930. Special Cases, Office of Student Affairs Records, Box 58, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01055, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Scrapbook, 1938-1966, Ancient Order of Hibernians Records, Box 3011.1, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00023, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

“Are Secret Societies Necessary,” Smith College Weekly, April 10, 1940. Ancient Order of the Hibernians Records, Box 3011.1, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00023, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

College Hall Occupation, 1986. College Hall Occupation, Student Demonstrations, Box CA Shared 128, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00317 Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Protest banners at College Hall, 1986. College Hall Occupation, Student Demonstrations, Box CA Shared 128, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00317 Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

footnotes

- Dellecese, Cheryl. “News of Note,” Smith College Website, published February 24, 2025. https://www.smith.edu/news-events/news/be-brave-set-high-goals-break-barriers ↩︎

- Laura Woolsey Lord Scales Papers, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00088, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, accessed March 14, 2025. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/resources/392 ↩︎

- Office of the Warden, Office of Student Affairs Records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01055, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, accessed March 14, 2025. ↩︎

- Ancient Order of Hibernians Records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00023, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, accessed March 14, 2025, https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/resources/145 ↩︎

- Scrapbook, 1938-1966, Ancient Order of Hibernians Records, Box 3011.1, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00023, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- “Why Smith and Why Now? A Look at the Events of February 1986”, May 2 1986. College Hall Occupation Oral History Project, Student Demonstrations, CA-MS-00317, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- Student Demonstrations, CA-MS-00317, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- “Students occupy Smith College administration building.” Feb. 26, 1986. United Press International Archives. Accessed March 24, 2025. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1986/02/26/Students-occupy-Smith-College-administration-building/5419509778000/ ↩︎

- “It Happened at Smith”, May 2 1986. College Hall Occupation Oral History Project, Student Demonstrations, CA-MS-00317 Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. ↩︎