In 1989, in response to student activism, which called for further education and reflection around issues of race and diversity at Smith College, Otelia Cromwell Day was created. In 2019, the name was changed to Cromwell Day to honor the legacies of both Otelia and Adelaide Cromwell. Today, Cromwell Day is a full-day event. Classes are canceled, keynote addresses are given, music is sung. Workshops and other performances are held in the afternoon and evening. It is a well-planned event, with a lot of intention put into organizing speakers and workshop design.

This project came out of a desire to connect the past to the present. The Cromwells deserve to be more actively recognized for their contributions to Smith College, civil rights, and society. Centering the Cromwells’ and connecting their legacy to current black students’ experiences at Smith feels especially vital today. The narrative you hear is the story of how Otelia and Adelaide came to Smith and their legacy beyond it, through the voices of current Black Smithies speaking about their experiences and reflections that connect them to the Cromwells.

Credits

Narration:

Stevie Ordway

Additional Voices:

Ari Cross

Tai Carson Smith

Kim Estrada

Music:

“Faded Expressions” music for your project by theoctopus559 — https://freesound.org/s/630530/ — License: Attribution 4.0

Transcript

Stevie: What does it mean to be black at Smith College?

Ari: I almost feel like I don’t have the words to answer it.

Tai: It’s a, it’s a surreal experience to be in a Harlem Renaissance class and be the fourth, and be like one of four black people.

Kim: It’s a lot about perseverance. Smith has painted its own narrative about what community looks like here…

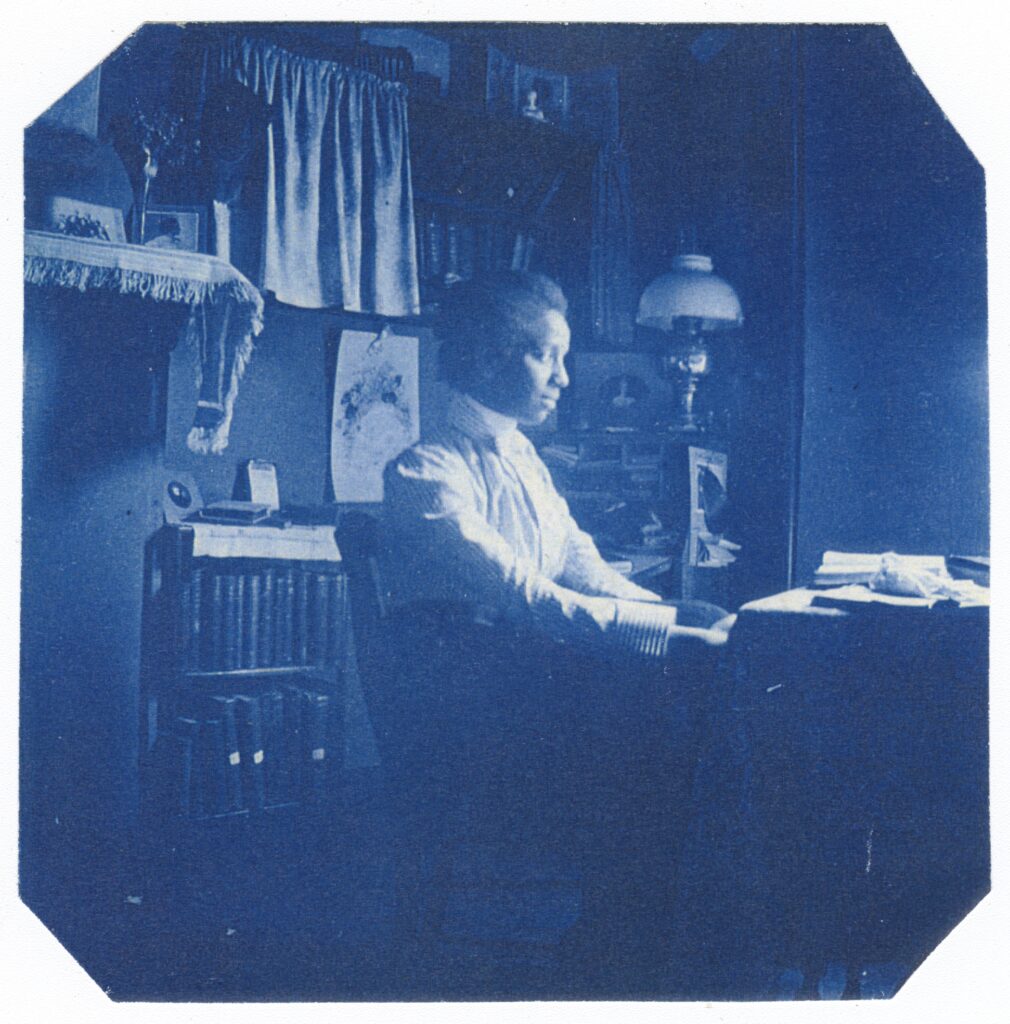

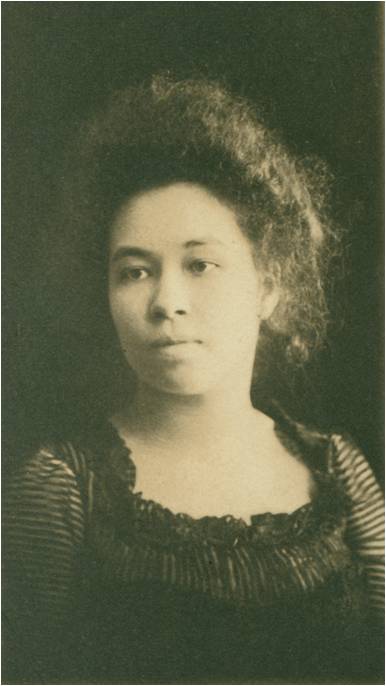

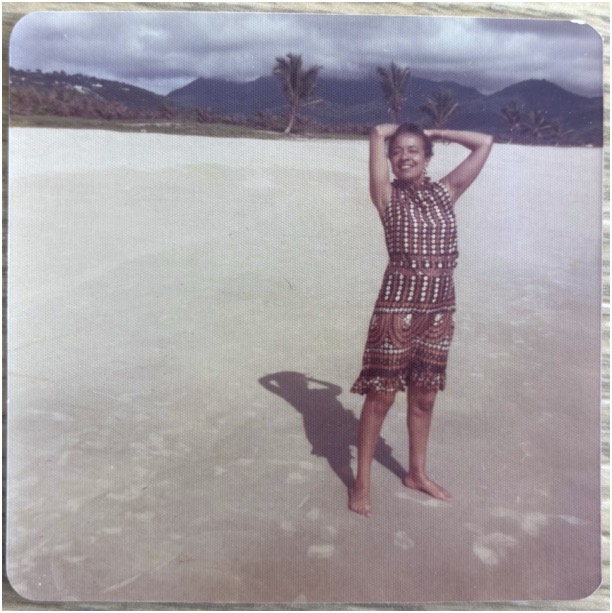

Stevie: In 1897, Otelia Cromwell transferred from Howard University to Smith College. She had been taking classes at the HBCU while teaching in Washington, DC, the same city she was born in 1874. Otelia’s mother died when she was 12, leaving her responsible for her five younger siblings(Otelia Cromwell Bio Yale). So she stayed at home working and going to school until she packed her trunks and loaded them up to make the trip to North Hampton and Smith College.

In 1898 and 1899, during her junior year, Otelia lived at 190 Roundhill Road with a sophomore named Inez Louise Wiggin; for her senior year, Otelia lived at 275 Main Street with no other Smith students at this point. There were two other black students on campus. Ethel and Helen Chesnutt. They began their enrollment at Smith as freshmen in 1897, a year before Otelia transferred as a junior, making the Chesnutt Sisters, in actuality, the first black Smithies(Smith College’s First Black Students).

The Chesnutt Sisters graduated in 1901. Neither of them was allowed dorm housing, and instead, they were forced to move to multiple off-campus locations throughout their time at Smith. This injustice led to advocacy from Otelia herself. Later in 1913, when Carrie Lee, a black student, was denied on-campus housing. Otelia wrote to President Burton, urging him to fulfill the promise he made to Carrie Lee upon admission.

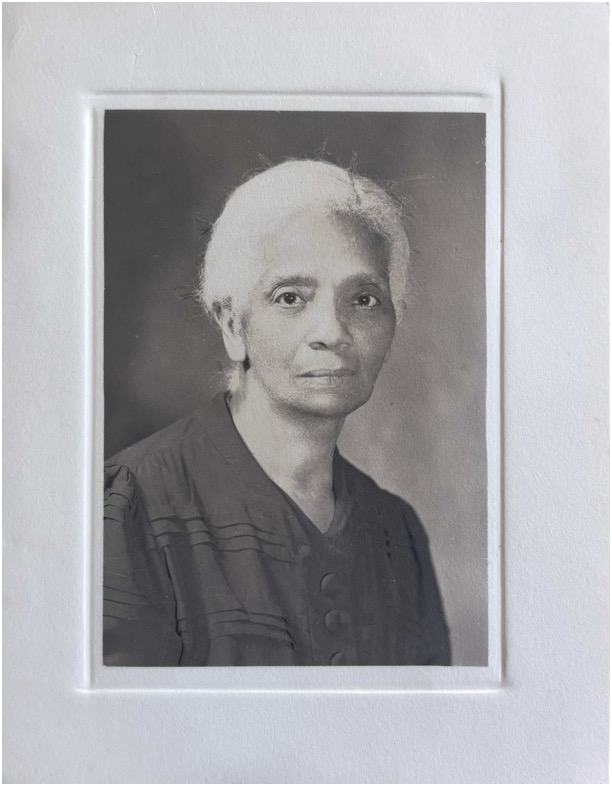

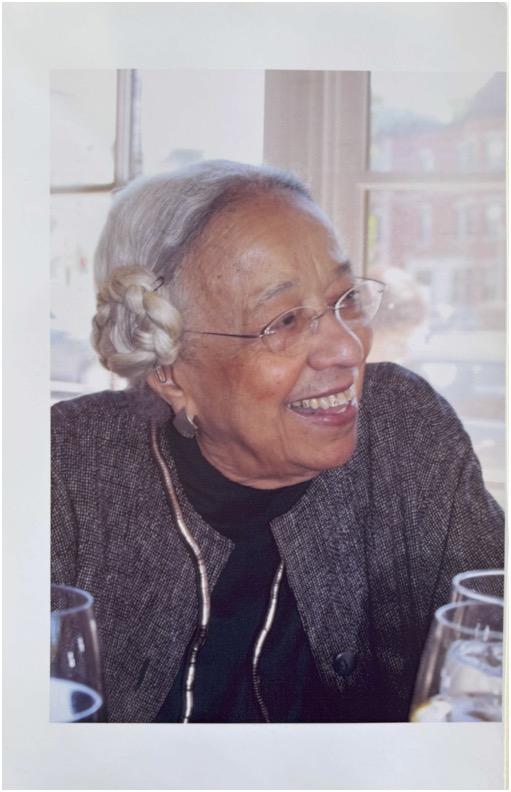

This led to the Smith Board of Trustees voting in October 1913 to deny all proposals to exclude students of color from on-campus housing(Transformative Inclusion at Smith College). Which meant that in 1936, when Otelia’s niece Adelaide arrived at Smith, she got to move into a dorm.

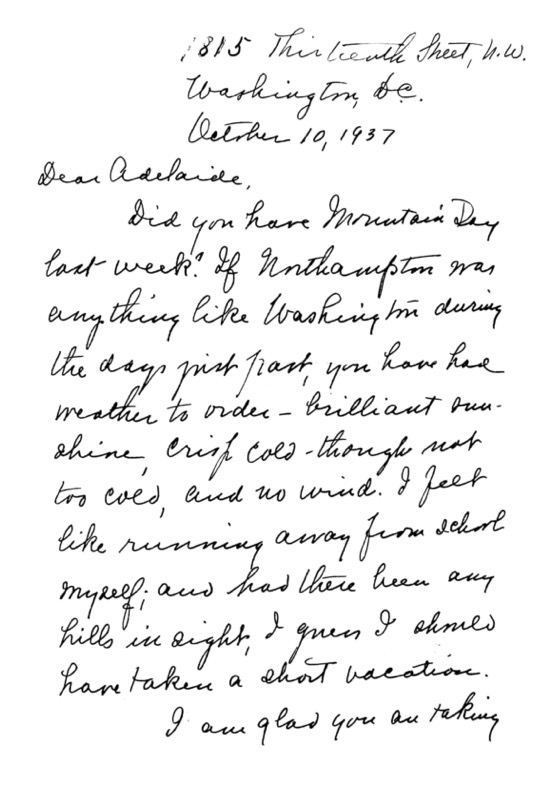

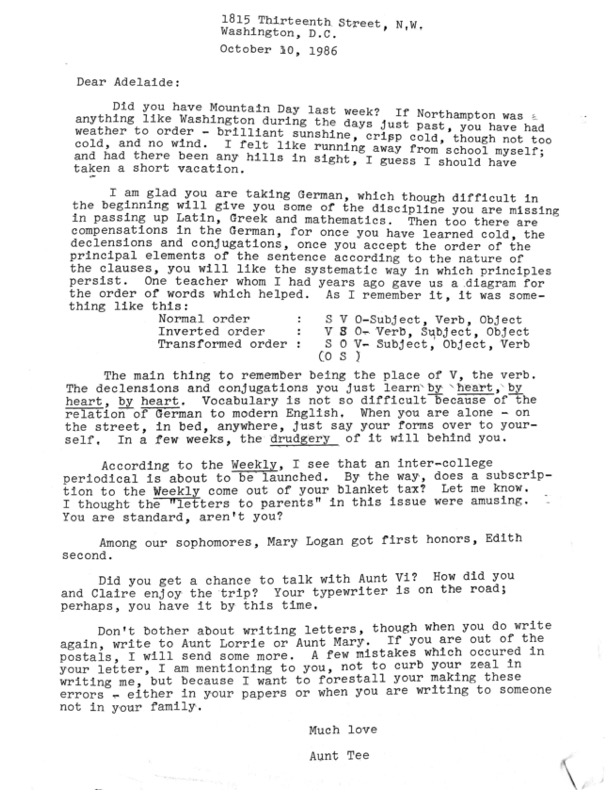

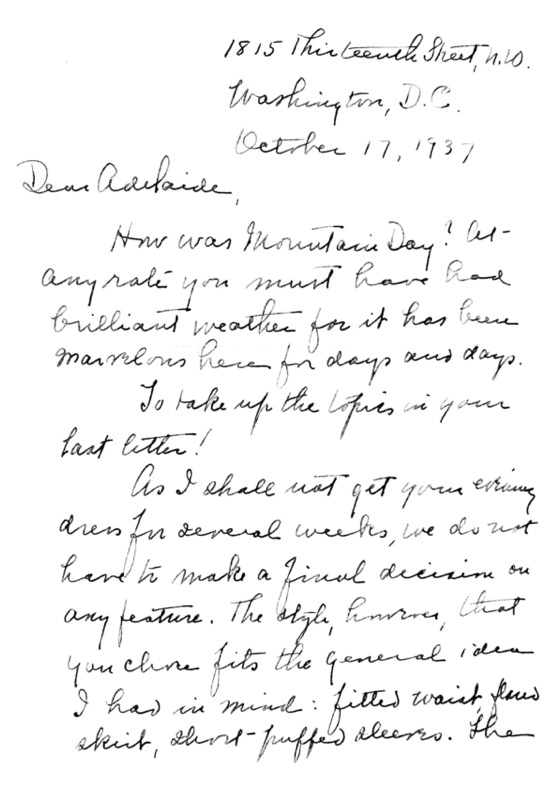

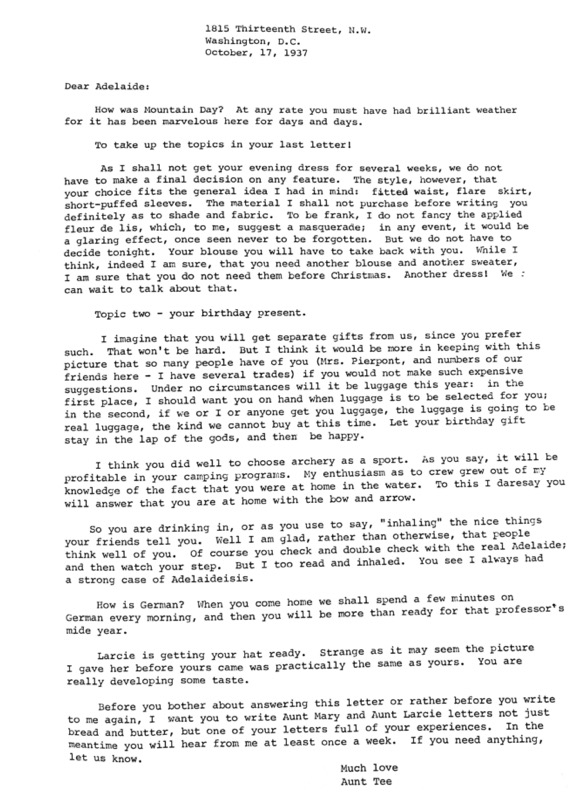

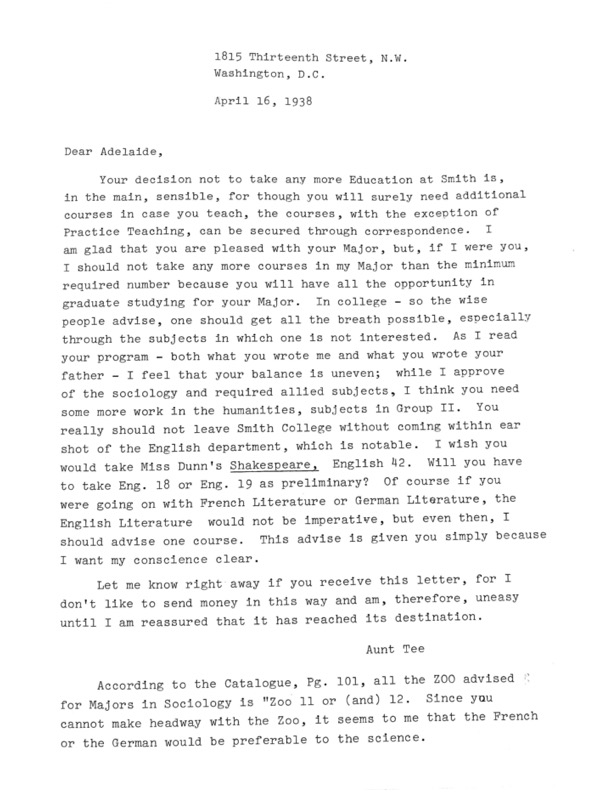

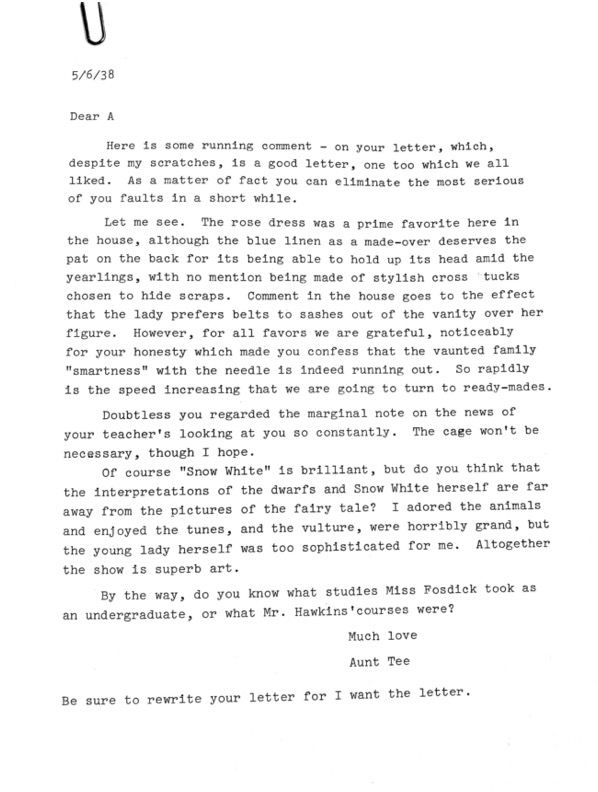

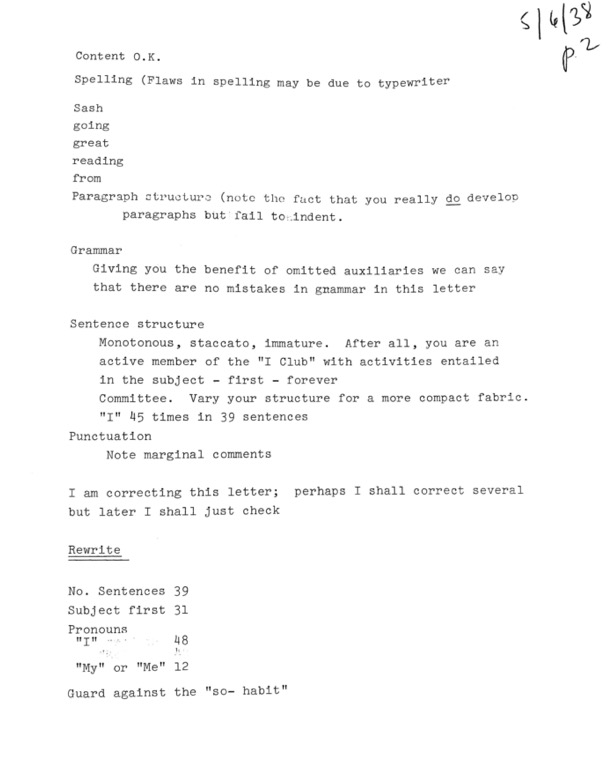

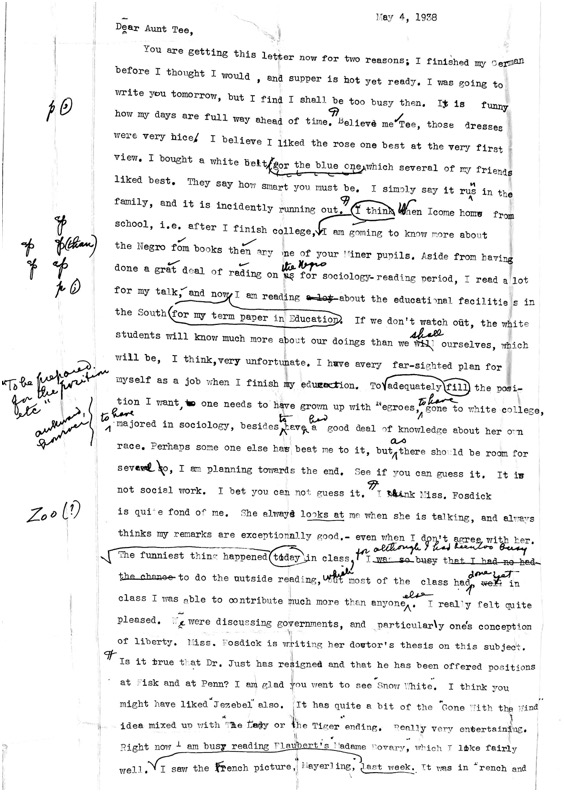

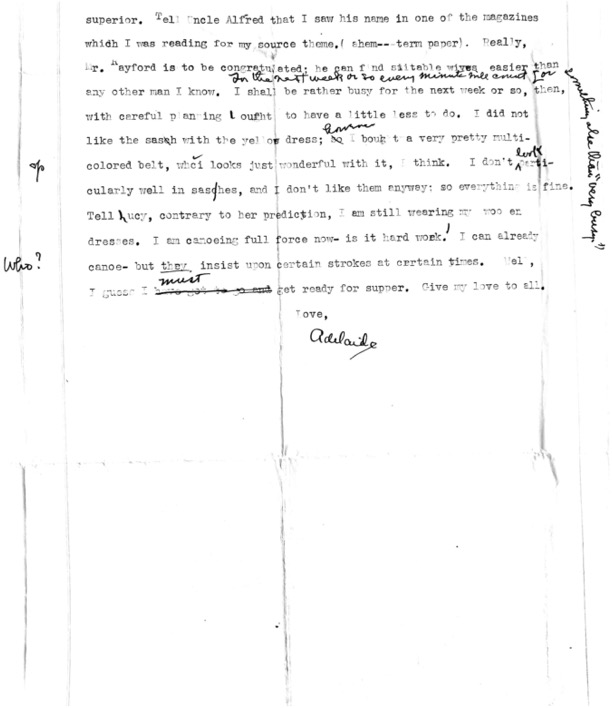

Adelaide moved into Smith College with the help of her mother, Yetta Mavritee Cromwell. Otelia wouldn’t return to Smith campus until after Adelaide’s graduation in 1940. During Adelaide’s time at Smith, there was much correspondence between her and Otelia. Aunt Tee, as she’s lovingly called, provides much guidance and advice. How to navigate a tough German teacher, how to write proper letters, what classes to take, even the details of Adelaide’s wardrobe, which Otelia seems to construct mostly herself with the help of her sisters.

To learn more about their correspondence during Adelaide’s years at Smith College, please visit (https://sites.smith.edu/beyondaday/).

Stevie: How do you relate to the Cromwells?

Kim: I think I just have a lot of respect for them in terms of being the, the first, there was a year where she was by herself. I think sometimes what bothers me about the narrative about Otelia Cromwell in particular is that yes, she was this great person, but what about the strife? What about the fact that there was probably people who did not wanna sit next to her? There was probably teachers who did not want to teach her. Um, she also had to live off campus, so how was she really a part of Smith community?

Tai: How many people, even in the faculty, really acknowledge much more about the Cromwell than the fact that Otelia was the first Black Smith student and that Adelaide was–correct me if I’m wrong–the first black teacher.

Stevie: Mm-hmm.

Tai: Right. And I feel like those two things are the most palatable to acknowledge. I feel like the thing that gets me about Cromwell Day is that it’s really Smith patting itself on the back for doing that thing. It’s very, it’s an example of the sort of performative nature around here that makes being a person of color hard.

Ari: Yeah. I certainly resonate with all of the being a first and like how hard it is to do that and how hard it is to stay in an environment that wasn’t initially created for you.

Tai: The legacy of Cromwell is best left in the hands of black Smithies who do the work to actually make their entire stories heard. To make it so that we know about the struggles they went through, not just how great it was for them to be there, to make it known how a lot of those still are not over for Black Smithies right now. To make it known how we are still fighting for everything that they fought for.

Ari: Creativity and knowledge building of my own. Um, and like accepting the fact that like the knowledge that I build is just as creditable or just as worthy of. Um, respect as like the knowledge that has been built before. Um, as far as like building tradition, it’s not a realization that I’ve always had.

Stevie: Mm-hmm.

Ari: Um, that was definitely like a large hurdle to hop over.

Kim: It was probably tough for her, but what Otelia did was exceptional. And so we must talk about the circumstances that allowed her to be that. You do a disservice to Smithies, truly, um, you do a disservice to how she lives on.

[Music]

Stevie: During her time at Smith, Adelaide worked towards a major in sociology. She may not have dealt with as many barriers as her aunt, but she still faced an uphill battle every day at Smith. Whether it was white mothers expressing their disgust that their precious white daughters would be sharing a bathroom with Adelaide, or professors leering at her as they teach like she was an exotic zoo animal.

Her friends were often her frontline support. Telling fellow students off when they made racist remarks about Adelaide, some instances of racism she didn’t even know occurred during her time there, and were told to her by classmates years later(Adelaide Cromwell Oral History).

Stevie: What is legacy to you? How do you make one?

Kim: Yo, the Cromwells did it big. Let’s talk about it. That is an ancestor, like she paved the way for so many people, generations of people.

Tai: I think legacy is what you leave behind for other people to build off of. In terms of the Cromwells, I feel like obviously they left a lot for us that we probably don’t even realize that we are still trying to build on as Black Smithies in shaping the experience of black people at the college.

Kim: One of my professors was like, Smithies, um, all carry the weight of the world on them. We carry that with us. Um, it would be an honor for me if I had a daughter for her to go to Smith. What is it to intentionally raise our daughters, even a radical shift in what it meant and what it means to be a woman. The acceptance of what it means to be a woman, like different, um, definitions of femininity. So yeah. When we talk about Legacy Smith and the seven Sister colleges are monumental for women and for queer people in particular.

Ari: Also too, with the amount of tradition that Smith has, it’s very much open to like creating your own tradition as well. The ability to community build and create something that’s your own on top of tradition–I think at a place like Smith that’s so old, um, I think that that’s really awesome. I think that what I’ve done on Smith volleyball has certainly been like breaking barriers. I think I may be the first I don’t know if this like stat is real, but I think I may be one of the first or few Black captains on Smith volleyball, what I was touching on earlier, which is that like adding tradition to what’s already what, what tradition we already have. Um, and I definitely think that that’s part of my legacy as a Black student athlete.

Kim: Yeah. I think when you even go into the archives, like Smith is rich in history and will probably continue to be rich in history. And I also view it as like what it means for the generations of women to have needed to survive the things possible for me to be here, which is also very monumental. Shout out the ladies for real like. [Laughter] Yeah.

Stevie: The legacy of the Cromwells spans generations. These women made a career in higher education, attainable for so many by being the first of their kind. We look to them as ancestors, leaders, and guides through a system that was not built for us or with our success in mind.

They were exceptionally young, Black, and gifted, naming their truth matters. We cannot forget the circumstances that made these women truly extraordinary. The Cromwells worked from within to push against the oppressive systems that kept black women out of education and leadership. Today, Black students continue to do the work of creating culture and community at Smith that is safe within a system that still does not fully recognize our struggles for equity and inclusion.

This is how our legacy ties to the Cromwells. We are living with our history on this campus, and we must look beyond a day to see the importance of what the Cromwells have to teach us.

[End]