The Chesnutt Sisters

(1881-1969)

Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College.

Ethel and Helen Chesnutt entered Smith College as freshmen in 1897. A year before Otelia transferred as a junior.

(1879-1958)

Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College.

Making the Chesnutt’s, the first Black Smithies. They both graduated in 1901, a year after Otelia Cromwell.

Like Otelia, the Chesnutt’s were denied on-campus housing. They lived at 95 West Street as freshmen, 10 Green Street as sophomores, 36 Green Street as juniors, and finally 30 Green Street in their senior year.

How they felt and dealt with the fact they were the only Black students on campus is unknown. There is little to no personal material about the Chesnutt sisters in the Smith College Archives. An entry from English Professor Mary Jordan’s diary sheds some light on the matter noting that the

“Chesnutt girls are having a hard time with the color line…”

Prior to their arrival at Smith College the Chesnutt household had quite the decision to make. Their father, Charles Waddell Chesnutt, had already decided that he wanted his children to have the best education her could afford. He had been limited in his own education and faced many difficulties as a young Black man in the South.

Excerpt from Smith College’s First Black Students: Letters and Other Texts Illuminate Smith Journey of Charles W. Chesnutt’s Daughters Ethel and Helen, 1897-1901

By Pamela E. Foster ’85, M.S.J. Nat’l Special Projects Chair, Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society

“Western Reserve University was first considered. It was a fine college; it was in Cleveland; the girls could live at home; the expense would be slight; most of their classmates were going there–such were the advantages set forth by their parents. But the girls objected. This last year at high school was a disappointment to them. They had not said anything about it because there was really nothing to be said. They were enjoying their lessons very much; they loved their teachers; their scholarship rating was high; yet they were not entirely happy. So, they said, they would rather go to Normal School and begin teaching as soon as possible, than to plod out to Reserve for another four years of drudgery.

The girls told them that when the Senior Class was organized, and its activities under way, they realized with shock and confusion that they were considered different from their classmates; they were being gently but firmly set apart, and had become self-conscious about it. They knew that if they went to Reserve this state of affairs would continue, and so they had made their decision.

Charles learned that one of their friends had explained the situation to them. “After all,” she had said, “you are Negroes. We know that you are nice girls, and everybody thinks the world of you; but Mother says that while it was all right for us to go together when we were younger, now that we are growing up, we must consider Society, and we just can’t go together anymore.”

When this dear friend came a day or two later to study some homework with the girls, Susan told her not to come again because her mother might object. “O, no,” replied the girl. “Mother does not mind my studying with Ethel and Helen; it is only in social relations that she objects.” “Indeed!” replied Susan. “Well, I object very seriously to your coming here to study with my girls -so please don’t come again.”

Charles recalled his visit to Northampton several years before (seven years ago in 1889) and, after discussing the matter with Susan, decided to send the girls to Smith College, where for four beautiful years they could breathe the air of New England, the cradle of democracy. When the decision was made, peace settled down upon the Chesnutt family….Susan was already planning the girls’ dresses for commencement, and their wardrobe for college….By February (of 1897) Chesnutt had written several stories and had made great progress on his novel. His shorthand business was very absorbing; his writing had to be done at night and on Sundays. He was making money and saving much of it, for he intended before long to give up business and devote himself entirely to literature. His plans however, must be postponed, for he realized that sending the girls to Smith would be far more expensive than sending them to Reserve.”

Activity: What does it mean to be excluded or forgotten by history?

If history lives within us how does these treatment of these women and their histories land in your body? What questions and feelings are coming up? Do you see yourself represented in the history books, in the archives?

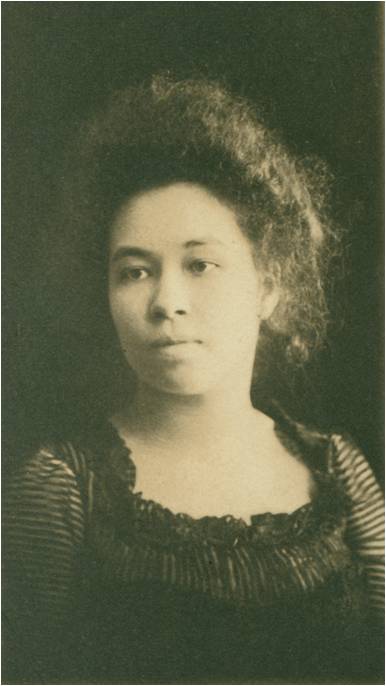

Other Forgotten Narratives

These images are from the Cromwell Family Papers and have no names or dates. The stories of these women are not easily told when there is little to go on. However, it doesn’t mean they should be overlooked, ignored, or forgotten. Finding these images during my research made me stop and appreciate the beauty in history and the power it has in representing our present.

Cromwell Family Papers, Smith College Archives,

CA-MS-01228, box 10