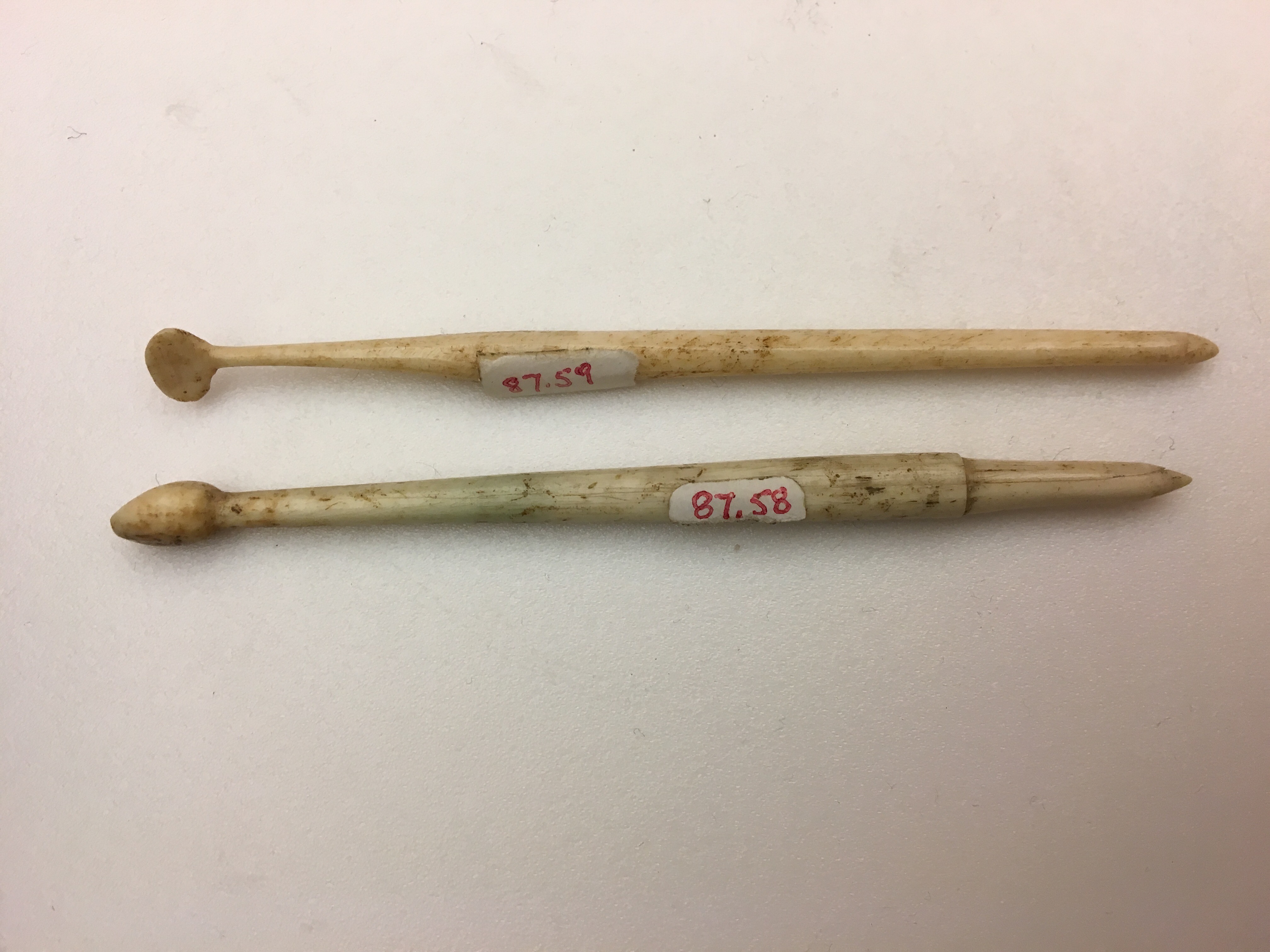

Roman Styli (SC 87.58-87.59)

MADISON VINCENT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Timeline

ARTIFACT MANUFACTURE

The craftsman embodies the central character in the manufacture report of the two roman styli, as their transformed purpose commences with their fabrication from raw material into a technology. Workshops in Roman settlements have been found in close spatial relationships to one another, which is the data based choice for including the butcher into the beginning of the narrative (Crummy, 255). This gives the reader a conceptualization of where the craftsman procured his raw material. In an effort to further the reader’s understanding this raw material, details were given to demonstrate a type of skeletal materials used in the region. Due to the limited meat in the average Roman’s diet, pig or veal would have been the two most common sources of skeletal material (Matz, 23). Furthermore, the price of ivory became more expensive during the 1st century CE as ivory sources declined due to the high demand for the material (Crummy 259). Using the information provided on the styli artifacts in the metadata, a broad date from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE has allowed some flexibility in the dating of the artifacts. To include this interesting socio-economic phenomena, this narrative has chosen to follow a date range from within that time period of the 1st century CE.

The benefits of bone styli over ivory styli also manifested in the popularity of bone pens as they were a stronger and more durable material. Where there is a cause for hesitation in the argument that the ivory stylus was crafted by a skilled craftsmen is a slight unevenness in the decorative line. Greater skill would have enabled the craftsman to mark a straighter line around the circumference of the writing pen; in addition to this quandary are the fractures along the points of both styli. Does the fracture on the ivory stylus or the chip on the bone stylus indicate a flawed creation process? Or could it be indicative of heavy usage? Further insight into the damages on the styli will be explored in the following essay, as it focuses on the long term stresses affecting the styli during their use.

“The relationship between the butcher and the craftsman had been established on their mutual need; the craftsman relieved the butcher of the bones which remained as animal waste. From one man’s waste, the craftsman applied his skill to transform the skeletal materials into tools which would be used in the daily functions of the Roman people. With each pig’s bone cleaned of residual fluids, it was possible to begin the process of item specialization. To create a set of writing pens (styli), one ivory and the other bone, the craftsman begins by picking out splinters from the bones that had been created during the process of marrow retrieval.

Starting from one end that would be carved into a point, for the purpose of making inscriptions onto a wax tablet, the process would carve the shaft into a wider gripping point for an author to comfortably maneuver the stylus. Finally the pen would be finished by shaping a flat head which would act to erase blemishes from the wax board. Within several minutes the craftsman has produced the small tool; leaving the pig’s bone material, the craftsman could move on to handle the ivory. As the demand for ivory overtook the supply coming from Africa the prices rose, and the craftsman had began to see less common use of the material. Taking more care while handling the more fragile material, the craftsman carved a small line of decoration around the inscribing point of the stylus with his carving knife. In addition to the broader circumference of the ivory pen, the altered appearance demonstrated a higher status indicating the more expensive product.”

ARTIFACT USE

An omniscient narrator was crucial to create the chain of possession that the pens would follow. Beginning with the exchange between the craftsman and the slave in the forum of Pompeii, the styli were exchanged for the value of two asses as they would not have been terribly expensive objects. I placed them at the price of two loafs of bread (“Guide to Ancient Roman Coinage.”), as I saw the ivory as an expense comparable to one and a half loafs. This also reflects the higher cost of the ivory, as it was a finite resource that was not able to be produced in accordance to demand. The analysis of styli value was limited by the minimal quantity of source material to be found on the worth of such objects.

Continuing with the possession of the two styli by the owner, dual purposes for the styli was described. The purpose of the letter that I conjectured would be to commission the fresco known as “Sappho”, Gaius uses the ivory stylus to cut letters in Old Roman Cursive (ORC) into the tablet. The wax tablet was used as a form of quick communication that could be reused and marked with a seal for official correspondence. The inclusion of ORC in the narrative as it is first evident in the first century AD, and commonly adapted for use with wax tablets (Clark 187). Additionally, the use of the bone styli by Marcus shows another purpose for the pens. It was common practice in Roman education for young students to trace stencils of the alphabet in order to conform to the ideals of memorization as the primary source of learning (Matz 3). Thus the dual nature of the pens are demonstrated. An important inclusion in the section is the use of the flat end as an eraser. Combined with heat a flat end could be used to resculpt a flat form in the wax if an error was made to the script (Brown 4).

The chips and cracks are not addressed in this narrative as it can be continued in the discarding of the artifacts. Owing to the possibility of reuse, a styli would not have likely been disregard unless broken. In my narrative, the styli have been crafted recently and it is unlikely that they would have developed flaws so quickly if they had been made properly. This accounts for the limitation in my narrative for the styli. I chose to demonstrate their original use in a single use, instead of over a long spatial period. It was my belief that I could best demonstrate the function of the styli using a solitary example of their social and economic implications as tools of communication.

In conclusion, I used an existing fresco to create a temporal and spatial relationship within which I could create an example for the use of the writing styli. The fresco “Sappho” is located in the city of Pompeii and was not uncovered until early excavations of the buried city. Misleadingly titled, the fresco depicts not the poet but a lady of high social class; demonstrated holding a pen and tablet, this woman becomes my muse as she creates a centerpiece with the pen (Meyer 569). It was possible to then show the pens as an economic trade themselves, but also as an indirect influence on a larger economic event in the commissioning of the fresco. Their purpose as stimulants of a social and economic agreement is most fascinating to me, as it grants them a larger purpose than their immediate structure emits. Thus a narrative for the styli was written.

“As the slave approached the craftsman’s stall within the forum, the craftsman laid one last inspection against the two styli he had been commissioned to make. Confident in his final product the craftsman prepared the pens for another critical study by the slave, who was responsible for safeguarding the owner from purchasing flawed objects. A cursory glance proved enough to satisfy the slave before he retrieved the 2 asses agreed upon for the price of the craftsman’s trade.

Exiting the forum, the slave jogged his way through the thick crowds accruing in the building heat of the day. His owner, Gaius, would be waiting impatiently for his return as the newly purchased styli were required to write a commission for a fresco. Upon his entrance through the vestibule, the slave was subjected to summons from the owner’s cubicula. Making his way through the atrium, the slave began gathering the wax tablet that would be used as the canvass for the styli to carve. His arrival in the bed chamber was met with an impatient gesture by the owner.

With the styli in Gaius’s possession, the owner began a letter detailing the fresco he had been planning in honor of his wife. Often he compared his sentiments towards his wife’s beauty to those detailed in the lyric poetry of the Greek poet Sappho, for whom he also dedicated his fresco to. Out of admiration for the craftsmanship of the ivory pen, he began impressing the tip along the clay tablet. As the impressions gave way to the lettering of old Roman cursive, Gaius stopped only to heat the flat end of the stylus and wipe away any mistakes he made in his hurry. As he wrote, his young son Marcus had sought out the bone styli to begin tracing an alphabet carved into a wooden board to practice his letter memorization.

Among his frantic scrawl, Gaius had failed to notice the arrival of the tabellarii whom Gaius had paid to deliver his letter. As he sealed the tablet, the letter carrier stood at the ready to receive direction for his route. After his fee had been settled the tabellarii found his way outside. As he hastily made his way through the streets of Pompeii, he carried with him the correspondence which would eventually be called “Sappho”.”

ARTIFACT REUSE

Central to this portion of the styli narrative is the alternative contexts in which it would have been used. Previously the narrative focused on the function of styli as means for communication, however I want to expand the functional properties of a stylus to include education and social status. Briefly mentioned in the previous segment of the artifact timeline, the son of the portrait commissioner had received one of the two styli for his own uses. In my narrative, the son is preparing to begin his education and must become accustom to the stylus and his new responsibilities. The contrast between his appropriation of the writing materials as toys and the memorization work required from Marcus serves to highlight his nearing development into a new age-set. I used this stylistic decision to create a fluid transition between the Use and Reuse portions of the timeline. As the stylus is shared between the student and pedagogue, I will demonstrate how the reuse of an artifact can provide a more holistic interpretation of the culture.

Education began in Rome as a product of the interactions between Etruscan and Italic peoples. Fathers were responsible for teaching their children, with supplemental visits by traveling professors. Traditional images of Greco influenced education began in the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC, which involved larger classes that began when children reached the age of seven (Matz 2-11). Students were expected to bring their own equipment and were typically accompanied by one to two slaves. The equipment necessary for a student would be the wax tablets and styli, as the Roman education system valued literacy as much as it did rhetoric. For the wealthier students pedagogues, educated slaves could act as tutors which further set them apart from their peers. (Bloomer, 9-21)

Through his experience tracing the alphabet, Marcus is preparing himself to grow into his next age-set. Once he can attend school new responsibilities will be expected from him, such as learning to write and contributing to his society (Conclusion 193-200). A proper education will become the foundation on which Marcus can establish himself as a social unit; literacy was an important aspect of social performance in ancient Rome. Literacy as defined in antiquity can resemble the recognition of high-frequency words and range to a full comprehension of written language (“Literacy in the Roman World.”). The stylus can then be seen as a social status that is afforded to those who can bear the economic impact involved in sending their children to school.

Low-income families are required to withdraw their children from school, as the economic pressures involved in the absence of their labor is too great. However, it was not uncommon in Rome for children slaves to attend school. Descriptions of Roman people’s treating their slaves as “favorite pets” encourages the idea that some slaves were sent to school. Further evidence is seen in the linguistic analysis performed by Alan D. Booth, where he suggests that the education of slaves was prevalent in first century Rome. Freedmen were also included in school, however they were likely to join the slaves for their schooling.

Consequently, we find Mardonius as capable of acting as a pedagogue for Marcus. His education gives him a lifestyle and status apart from other slaves, as he is now responsible for the mental upbringing of his young master. It is conjectured that a pedagogue also received a special status within the family, due to their intimacy with the children. Some witness accounts have deemed the pedagogue as equivalent in their respect to their father (Yannicopoulos 173-79). To conclude my interpretation, I wish to emphasize the styli as a metaphor for education and the subsequent status it provides to the hand that wields it. Through a contractual agreement, developing literacy, and acting as a tutor each of the characters use a stylus to advance or secure a better position for themselves in Roman society.

“Marcus sat in the back of his father’s cubicula. Empowered by a sense of pride, the six year old jabbed the bone stylus against a wooden stencil used to help him memorize letters. At six and a half, Marcus was nearly ready to begin his lessons with the literator and his angst to grow up powered each awkward tracing of a letter. The stylus and trace board had been a present from his father who had already begun to start his informal education. As his focus began to wane, Marcus’s strokes became more and more clumsy causing the point of the stylus to chip against the board’s wooden edge. Dismayed with his newly broken equipment, Marcus’s developing attention began shifting towards more exciting activities. Inspired by the soldiers he saw each day patrolling the city, the boy began scraping wax off of his father’s wax tablets to use as a wax model.

Crude and disproportional, the soldier stood falling to one side as his left leg had been formed shorter than his right. Marcus began strutting the soldier around the wooden surface, which had been transformed into city walls that could be patrolled by it’s newest defender. Thinking quickly, Marcus used the stylus in the place of the soldier’s weapon. With his fortress complete, the young boy began reaching for further resources to bolster his army.

When Mardonius stumbled across his new charge, the boy sat with his hands full of wax that was intended to be spread across newly stripped wood panels. Although he had yet to create trust amongst his family, the pedagogue wasted no time in sparing himself from the certain wrath that awaited him if further tablets were damaged.

“Young Marcus, your letters seem to be coming alive. What form of memorization have you been practicing in my absence?”, with a start Marcus began to smush the wax on the tablet.

“I was tired and you have to teach me better. My pen broke. It was hard and I want to have fun.” This simple retort was all that the young master offered. Although it was the responsibility of the pedagogue to aid in the education of the young boy, he found that the boy had yet to stop treating him with the same manners he treated the other slaves when he wanted to avoid trouble. Fortunately, Mardonius knew that his responsibility to tutor the young master included having him perform alphabet tracings; an activity which was quickly losing the young boy’s attention.

“Return to your board. You should have five more letters memorized by the end of the day. M, A, R, C, U, and S. You ought to at least know your name by now. Come look, here’s how it is spelled.” Mardonius began impressing the boy’s name on the lumpy remains of the soldier. “See, if you practice hard enough you will have much nicer handwriting than my chicken scratch.”

Marcus was captivated by the sight of his own name being written, which was unsurprising to his pedagogue, as Marcus found the most entertainment from himself. The young boy returned to his straight backed position against the wall, clearly straining to mimic the actions he had just witnessed.”

ARTIFACT DEPOSITION

In order to best explain the deposition and current conditions of the ivory and bone styli, evidence from 4 archaeological studies will be used to support that narrative I have illustrated to contextualize a location for the burial and damages associated with the artifacts. Beginning with an analysis of the relationship between domestic space and artifact distribution, Penelope Allison suggests that a room is less likely to be defined based on structural features than the artifacts that are found seemingly out of context in the room (Allison, 20). Allison’s analysis, which uses daily artifacts as the defining feature when discerning the function of a room, has been elaborated upon in numerous studies of the “atrium style” Roman household as it focuses the archaeological study on the inhabitants rather than the structural build (Allison, p. 20). This argument has turned Pompeii into a case study for determining how individual kin groups change the functionality of permanent structures to adapt to their individualized, socioeconomically driven needs. Objects that move throughout the structure can show up in the archaeological record as indicators of socioeconomic variation left in de facto refuse when put in context of abandoning a household (Baird, 62). This theory states that an object in daily use would remain in its final location of use after the time of the settlement’s abandonment (Baird, 62). Using Baird’s (2006) concept of de facto refuse to explain a possible deposit location for the styli, I selected the atrium based on a curatorial report published by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (Cannatella, 7). Based on a material study of Roman “atrium style” households, the curatorial report supported the same principles of artifact determined functionality proposed in Allison’s work on Pompeian domestic spaces (Allison, 20).

Accounting for the condition of the ivory stylus in this domestic setting proved more challenging than proposing an explain for the small flake missing from the point of the bone stylus. Research into different fracturing patterns present in bone tools uncovered what type of fracture pattern present on the ivory stylus. The crack runs parallel to the longitudinal axis of the bone and in the same direction of the grain, which is consistent with a longitudinal fracture. This stress pattern is consistent with a sharp force that turns mircocracking into a full fracture (Fuld, 2011, p. 9). The single, uncontrolled sharp force trauma caused by the Father’s terrified reaction is consistent with the stress pattern required to break the bone.

Additionally, my choice to associate the styli with the bone needles was a preferential decision meant to create context for their future assemblage at Smith College. As they all share similar, broad provenances in time and space an allusion provided possible context for future narrative additions to the assemblage’s collection. Further support for this allusion was provided in the preceding archaeological evidence for the movement of artifacts through the domestic space by way of material evidence for weaving in common areas(Allison, 20). A gender based component of Allison’s theory portrays the uncertainty of assigning gender to an artifact with this theory (21). Pictorial and textual evidence can suggest and inform scholars of potential population that could be using any given artifact, however the representations given in the depictions have to be controlled for their subjective biases and intentions (Allison, 21).

Finally, I chose to further engage my objects in a spatial and temporal moment during the eruption of MountVesuvius in 79 AD to provide the styli with a concrete historical date. This method of connecting the objects to a known event is similar to my artistic choice to reference a well-known painting of Sappho or a wealthy woman in Pompeii. Providing a concrete, yet dramatized, image of their deposition creates a context that attracts a greater audience with a universal theme of human suffering. Although the deposition provided for the styli is based in fiction, the styli still follow an intended structural deposition. This is the most probable cause for their deposition as both styli display damage to their points. Whether the styli waited for acquisition in a midden heap or suspended in ash at Pompeii the styli were consciously discarded, which provides the narrative with a stronger resolution. All together the narrative uses archaeological evidence as a basis for illuminating their intersection with human experience.

“Together the Aemilius family lounged in their atrium, basking in the luxury of their well-tended gardens. Musing over a half finished wax tablet he was writing for a friend, Gaius swept his eyes across the courtyard to evaluate what progress Mardonius made with his son. As he was yet to feel pleased by any advancement with his son’s work, Gaius remained wary of the investment he had made on the pedagogue. Although Mardonius attempted to keep Marcus busy practicing his letter memorization, the boy seemed more interested in using his bone stylus as a toy sword. His uneasiness lingered as he witnessed the informality with which Marcus and his tutor addressed one another.

Remembering his tablet, Gaius suppressed his doubts and refocused his own literary endeavors. As the patriarch began to draw the ivory stylus towards the waxen palate, a thunderous roar thrashed through the city. In the chaos of the trembling exaltations of putrid smoke, the ivory stylus was cast against the tablet causing a fracture to rip through the once carefully crafted writing implement. Time slowed in contrast to the quickening storm that was seen rippling down from the mountain. Vesuvius. Any tool that had once been held by the family was strewn across the atrium as the family frantically raced to spare their most expensive possessions.

Following the family’s evacuation, hot clouds of ash swept down upon the empty atrium. The ivory and bone stili lay in thrown about the ground alongside an assemblage of needles which had been used by Marcus’s mother for textile work; they had been left in the family’s hasty retreat. Within minutes, the last of Gaius’s massage was blanketed by volcanic ash: it read “a.d. ix Kal. Sept. DCCCXXXII A.U.C.”.”

ARTIFACT ACQUISITION

Several factors resulted in creating an intentionally vague narrative for the acquisition of the Roman styli present in the Smith College collection. Responding to the lack of documentation surrounding the provenance of the styli, looting is suggested for their manner of introduction into modern archaeological records. The general term looting in archaeological discussion minimizes the failure of professionals to respond to the commercialization of artifacts by private collections. Rather the blame has fallen largely on to the indigenous diggers that have used the demand of commercialization to support themselves on their own cultural heritage (Hallowell, 72-74). The vagueness of the styli narrative allows me to respond to the critiques on subsistence diggers as well as the limitations in publishing responsible narration based on the absence of literature on Roman styli.

Subsistence digging largely gets diminished under the umbrella term of looting, this misclassification of the social factors driving indigenous populations to benefit from the commercialization of their ancestral heritage. Socioeconomic disadvantages and systematic oppression by the state increasingly serves as the catalyst driving local people to supply the demand for valuable artifacts (Hallowell, 74-79). Foreign archaeologists, often times supported by the same oppressive state, have been responsible for the vilification of indigenous populations that use subsistence digging as a means of survival. Hallowell’s argument supports indigenous populations protesting the state sponsorship of foreign archaeologists in Sicily (76). Responsibility that falls upon the socioeconomically disadvantaged is cause for greater concern in the archaeological record as it continues dated methodologies that separate the indigenous from their cultural heritage once again.

Systemic issues of provenance in the archaeological record can also be traced back to the dissociation of the object to it’s rightful cultural ancestry. In the narrative of the stili, I was able to use the ambiguous nature of the documentation surrounding their provenance to demonstrate how scholars in the twentieth century irresponsibly handled artifacts without a provenance. Without the benefit of empirical evidence for the provenance or transference of the stili I made the decision to elaborate upon the ambiguity in the narrative. I chose to keep the titles of people and places unnamed as it enables this narrative to be removed from the context of the timeline project as a narrative for any object. This techniques is supposed to demonstrate how the stili, or any unprovenanced artifact, have been denied their right in the archaeological record to belong to a cultural heritage. The scholars who bought or excavated these artifacts have not left behind sufficient evidence within the Smith College or greater academic world to retrace their acquisition process, further distancing them from their own history.

Without empirical evidence for the process in which the styli were acquired for the school, I had to follow a general pattern of seventh degree separation to trace the history of the styli. The Van Buren Antiquities Collection was purchased for Smith College from a collection created by Albert Wilson Van Buren at the American Academy in Rome. Professor Warren Wright purchased the collection from Van Buren in 1925 to establish the beginning of an educational collection at the College (Bonfante, Nagy, 46; Bradbury). As this is the most common transference of material into the archaeological record I established a commercial relationship as the method in which the styli were acquired. However, without an inventory to determine the consumer or the vendor I maintained the ambiguity as to not rely too heavily upon conjecture to create a narrative.

“Silence, broken only by the soft movements of a man focused on the ground beneath him, lingered in the atrium. Silence had permeated throughout the ancient structure, which had been kept isolated until the 18th century had introduced it to a new world. Desecrated and left exposed, an emptiness echoed across the site as each stick of the spade hit the earth and each artifact was lost inside his dark, well worn satchel. Across the atrium, the styli were inspected briefly before being transferred to the dark interior of the satchel which seemed to swallow the styli as entirely as the volcanic ash they had just left.

Re-emerging from the satchel, noise proliferated around the styli. Migration had carried the writing pens to a contemporary, yet familiar sight. Lined on a small tray, the pens sat amongst one portion of a Roman palazzo waiting to catch the peering eyes of a passerby. Amongst the noise and the more glamorous artifacts, the simple styli lingered with their innate promise of untold stories. Hands well versed in the written word, but unfamiliar from the development of new writing technologies were drawn to the styli. Curiosity over their humble origin and their once intimate function drove the scholar to purchase the objects, removing them from the shock of the lively courtyard.

Removed from the shock of their sale, the styli found themselves in a small room, compiled in an assemblage of pot sherds and votive offerings. Once they had been catalogued into the collection the styli remained untouched. Buried behind artifacts more puzzling to the scholar, the styli were only uncovered once they were removed from the quiet shelves where they remained. Packaged securely in a crate, amongst several other domestic utensils, they were once again submerged in darkness. Darkness that only emerged after their long journey across the ocean to Massachusetts in the United States. There, they remained packed in storage. Light reached them once, when there lid was removed and they found themselves at the inspection of new, equally well versed hands, hands that were strengthened for writing with modern technology. The awkwardness with which they were held was telling of this spatial distancing. At last, they found themselves moved into a nearby college and unpacked amongst the same domestic utensils they had shared a crate with for the past fifteen years. However now the styli sat amongst other artifacts of daily life, visible to all.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allison, Penelope M. “The Household in Historical Archaeology.” Australasian Historical Archaeology, vol. 16, 1998, pp. 16–29., www.jstor.org/stable/29544411.

Baird, J. A. Housing and Households at Dura-Europos: A Study in Identity on Rome’s Eastern Frontier. Thesis. University of Leicester, 2006. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Web.

Bloomer, W. Martin. “In Search of the Roman School.” In The School of Rome: Latin Studies and the Origins of Liberal Education, 9-21. University of California Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pn81s.5.

Bloomer, W. Martin. “Conclusion.” In The School of Rome: Latin Studies and the Origins of Liberal Education, 193-200. University of California Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pn81s.13.

Booth, Alan D. “The Schooling of Slaves in First-Century Rome.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 109 (1979): 11-19. doi:10.2307/284045.

Bonfante, Larissa, Helen Nagy, and Jacquelyn Collins-Clinton. The collection of antiquities of the American Academy in Rome. Ann Arbor, MI: Published for the American Academy in Rome by U of Michigan Press, 2015. Print.

Bradbury, Scott. “History.” Smith College. N.p., 15 Mar. 2011. Web.

Brown, Michelle P. “The Role of the Wax Tablet in Medieval Literacy: A Reconsideration in Light of a Recent Find From York.” The British Library Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 1994, pp. 1–16., www.jstor.org/stable/42554375.

Cannatella, Anna-Maria. Within the Atrium: A Context for Roman Daily Life. N.p.: Anna-Maria Cannatella, n.d. Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Web.

Clark, John R. “Early Latin Handwriting and Plautus’ ‘Pseudolus.’” The Classical Journal, vol. 97, no. 2, 2001, pp. 183–189., www.jstor.org/stable/3298394.

Crummy, Nina. “Working Skeletal Materials in South-Eastern Roman Britain.” Agriculture and Industry in South-Eastern Roman Britain, edited by David Bird, 1st ed., Oxbow Books, Oxford; Philadelphia, 2017, pp. 255–281, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1kw2bfx.18.

Fuld, K. A. The Technological Role of Bone and Antler Artifacts on the Lower Columbia: A Comparison of Two Contact Period Sites. Dissertations and Theses. Paper 580. 2008.

“Guide to Ancient Roman Coinage.” Guide to Ancient Roman Coinage – Littleton Coin Company. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2017.

Harris, William, Professor. Sappho: The Greek Poems. N.p.: Middlebury College, n.d. Pdf. http://community.middlebury.edu/~harris/Sappho.pdf

Hollowell, Julie. “Moral arguments on subsistence digging.” The Ethics of Archaeology. N.p.: Cambridge U Press, 2006. 69-93. Print.

Horsfall, Nicholas. “Rome without Spectacles.” Greece & Rome 42, no. 1 (1995): 49-56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/643072.

Krzyszkowska, Olga. “Classical Handbook 3: Ivory and Related Materials.” Bulletin Supplement (University of London. Institute of Classical Studies), no. 59, 1990, pp. ii-109., www.jstor.org/stable/43768461.

“Literacy in the Roman World.” Accessed March 26, 2017. http://documents.routledgeinteractive.s3.amazonaws.com/9781138776685/Ch8/Literacy%20in%20the%20Roman%20World.pdf.

Matz, David. “Education” Daily life of the ancient Romans. (2009): 1-11 Hackett Pub. Co. Print.

Matz, David. “Food and Dining.” Daily Life of the Ancient Romans. N.p.: Hackett Pub., 2009. 23-33. Print.

Meyer, Elizabeth A. “Writing Paraphernalia, Tablets, and Muses in Campanian Wall Painting.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 113, no. 4, 2009, pp. 569–597., www.jstor.org/stable/20627619.

Pearce, John. “Archaeology, Writing Tablets and Literacy in Roman Britain.” Gallia, vol. 61, 2004, 43–51., www.jstor.org/stable/43607827.

Stern, Wilma, Danae Hadjilazaro. Thimme, and Martha Breen. “Nature of the Materials and the

Craftsmanship of Late Roman Ivory, Bone, and Wood.” Ivory, Bone, and Related Wood Finds. Leiden: Brill, 2008. 13-32. Print.

Yannicopoulos, A. V. “The Pedagogue in Antiquity.” British Journal of Educational Studies 33, no. 2 (1985): 173-79. doi:10.2307/3121511.

MEDIA CREDIT

Smith College, Van Buren Antiquities Collection

Fancy a butchers?, Walbrook Discovery Programme

Category: Sappho fresco (from Pompeii), Wikimedia Commons

Ancient scrolls: where are the wooden handles?, Found in Antiquity

A Set of Four Watercolors of Ancient Ruins, Circle of Ducros, 1800-1810, Burden