Isabella Levy, Smith College ’17

Table of Contents

Eutropios (Manufacture)

The Archaic Tanagra craftsman’s district hummed with life from the earliest hours of the morning. Slaves and apprentices heaved brushwood into earthen kilns while potters and painters gathered their materials and began their day’s work. In the coroplasts’ workshop, young Eutropios trailed his mentor and uncle, Theotimos, helping the artisan with his morning routine. As a younger boy, Eutropios had worked alongside his father and brothers on the family farm, tilling the fertile Boeotian soil, just outside the urban limits of Tanagra, but a mishap on horseback left the young man disabled. Luckily, Eutropios’ uncle was able to take Eutropios on as an apprentice in his terracotta business. Sometimes Eutropios would wonder if his father had agreed to have him employed at the workshop in order to hide him away from the public eye, but he tried not to wonder too much.

It wasn’t too hard for Eutropios keep his mind off those gloomy thoughts, however, since he found working with his uncle to be engrossing. He loved the slick lumpiness of clay in his hand and the sense of accomplishment that rushed through him when he began to tease a human form out of what started as a simple block. Because he was still an apprentice, Eutropios was not yet permitted to create more complicated figurines, but he was content in trying to master the simple plank-shaped goddess statuettes with which he was assigned.

After finishing with his morning chores, Eutropios sat down at his work station, set aside his cane, lifted off his chlamys, and went to work. He picked up one of his works in progress, a votive in the shape of a goddess. The figurine was about a hand tall, with a slender, flat body, and stubby arms about six fingertips apart. Its face was pinched into a thin, mouse-like shape, and its head was topped with a voluted polos, a cylindrical headpiece with a spiral decoration jutting from its front. A flared base allowed it to stand on its own. Eutropios had hand-crafted it all on its own, and he was proud of the evenness he was able to achieve even without using a mold.

Eutropios was about to test out a style of figurine painting, relatively new to Theotimos’ workshop, which had previously decorated all of its figurines with a three step black glaze firing. Recently, however, an Athenian metic had come to work in the shop, and he had shown Theotimos and his apprentices a new technique from his home city. A uniform slip of pale yellow or white clay required only one firing and could be further embellished with a variety of colors. Eutropios had already fired his figurine. He mixed together a tawny red pigment from ochre and egg albumen and began to decorate the piece. He painted eyes onto the face, indicated the goddess’ hair with two wavy lines down the side of her neck, and sketched out the basic outline of her dress, which he then adorned with a menander pattern across the chest and a series of vertical stripes down the rest of the body. He then whipped up another egg mixture, this time black with soot, to fill in the polos and place a large, round pupil in the center of each eye. The lines were a little sloppy, but that, he assured himself, just gave the piece a unique charm. Besides, he had no time to dwell on his mistakes. There was plenty more work to be done.

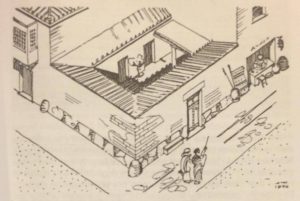

In this write-up, I argue that my artifact, like other similar plank-shaped figurines from Archaic Boeotia, was hand made in a workshop in Tanagra. Tanagra was a center of terracotta figurine production in the Ancient Greek world, throughout various periods in Greek history. Since my figurine is known to be Boeotian, and since Tanagra itself is located in Boeotia, I felt that it was justifiable to posit that the piece was produced there rather than in Delphi, where Van Buren purchased it. Figurines from Tanagra were crafted through a variety of means, including molding and wheel-throwing, but Reynold Higgins writes that the mouse-face and bird-face flat figure type, of which this figurine is an example, were hand-made (Higgins, 75-76). Violaine Jeammet indicates that the Tanagran coroplasts who created these mouse-face and bird-face statuettes operated out of workshops, in close quarters with potters, from whom, he claims, they borrowed the decorations used in rendering clothing (Jeammet, 41). Although a simple project such as my figurine could possibly have been crafted in a domestic setting, provided the craftsperson had access to a kiln, I chose to take the more obvious route and set my narrative in a workshop.

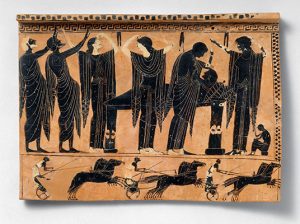

My narrative particularly focuses on the painting of the figure, as the Archaic period was a time of transition in Boeotian figurine painting. The earlier “black glaze firing” technique, which required three steps, was increasingly being replaced by “polychrome firing,” which required only one. The “black glaze” technique is quite similar to the process by which black-figure pottery was fired and painted, and it began with the application of a highly refined, iron-rich clay slip to embellish details (Higgins, 68). The piece was first baked in oxidizing fire, then the atmosphere in the kiln was converted to a reducing state by adding green wood or damp sawdust to the fire and closing off the kiln to the entrance of air. This produced carbon monoxide gas, which would chemically convert the red ferric oxide in the terracotta to black ferrous oxide, turning both the body of the figurine and the slip black. The kiln was then opened to air, and the black ferrous oxide was converted back to red ferric oxide. Since the body of the figurine is more porous than the slip, it would turn red first, and the process could be interrupted while the glaze decoration remained black (69). This process, which was popular from about 625 to 550 BCE, required a complex manipulation of temperature and kiln environment. The polychrome technique, which was developed in Athens around 550 BCE, was far simpler (69). The figurine was covered in a slip of pale yellow or white clay and then fired only once. After firing, more colors were added by brush, which allowed the introduction of more colors and colors not used in pottery (69). Pigments were probably bound in a tempera style, possibly using egg albumen, and color sources included red ochre for brown-red paints and soot for black (70). Both techniques relied on a clay or mud-brick kiln, fueled by brushwood (69). It is the presence of two colors, red and black, as well as the pale body of my figurine from which I drew the conclusion that it had been painted according to the newer polychrome technique.

I exercised more creativity when it came to the identity of the manufacturer. When trying to envision who crafted this object, I wanted to account for its particular attributes as well as my own representational agenda. In a time when molds and wheels were available to coroplasts, who would have created such a simple piece in such a simple fashion? Perhaps the craftsperson was an apprentice, someone as yet uninitiated in the more advanced techniques of the trade. Thus, I decided that my craftsman, Eutropios, would be an apprentice. I was also invested in this narrative (as I will be for every step of the object biography process) in bringing to life individuals and subjects not typically represented in writing about the Classical world. It was this goal that helped me decide to depict Eutropios as disabled. In Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks, Robert Garland paints a bleak picture of disability in Ancient Greece was bleak – and accurately so, I’m sure. However, he made it seem as if there were absolutely no opportunities for disabled people in Ancient Greece to live full and meaningful lives. I wanted to push back against that assumption (which in many ways may be influenced by our own biases regarding the contributions of disabled people) and see if I could tell the story of a young disabled man who engaged with his community and developed passion for a craft.

Anthousa (Use)

Anthousa pushed her way through the crowded marketplace of mid-5th Century Tanagra, making for the nearby temple to Aphrodite. Clasped in her left hand was a small terracotta figurine, with a flat body, a pinched face, and a simple painted design that made it clear the statuette represented a goddess. Anthousa walked alone, something that was unusual for a woman, but as a hetaira, a high class courtesan, she had some leeway to move through the city in unconventional ways. Besides, she could take care of herself. She didn’t need a chaperone.

As she approached the temple of the goddess, Anthousa spotted Pamphile, one of the temple priestesses and an old friend. Pamphile caught sight of her, too, and smiled. The two had met a year or so ago when Anthousa began picking up clients around Aphrodite’s temple. When Pamphile had a free moment, she would sneak away to chat with Anthousa, and it didn’t take long before the two grew close. Today, Pamphile’s glance was particularly tender. She knew why Anthousa had come to the temple. The two had discussed it earlier that week.

“I’m pregnant,” Anthousa had admitted.

Pamphile was concerned. “I thought you used wool to close up your womb!”

“I did,” Anthousa replied, “I don’t know what happened. But I can’t have a baby. I’d lose far too much business during the pregnancy, and supporting a child on my income wouldn’t be easy.”

“Do you know who the father was?”

“I think so. Andronikos.”

“He doesn’t have a wife, why not settle down with him? He could provide for you, even if you couldn’t really get married. You could live together and have a pallake. At least it would keep you and the baby comfortably accommodated.”

Anthousa considered her friend’s suggestion only briefly.

“I don’t know… I’ve worked so hard for what I have now. I saved and saved to buy my freedom from the brothel owner who bought me when I was just a little girl and now I’m one of the most sought after women in the city. Sure, in the short term I’m under obligation to one man or the other, but no more than the average wife! And unlike those women, I can move around the city as I wish. I get to go places and see things most women would never dream of. Just the other day, that wealthy man Stephanos asked me to accompany him to a symposium! He says Olympiodoros the poet and Iason the philosopher are going to be there! The more popular I am, the more money I make, the more choice I can have over which men I take on as clients. I don’t want to give that all up and tie my whole life down with one man. Not just because of some baby.”

So, she decided on abortion. She had gathered the necessary materials – rue, myrtle, sweet bay, and wine to mix it all in – but she knew how dangerous the process could be. That was why she was on her way to ask Aphrodite’s protection. As she entered the temple and made ready to dedicate the votive figurine, Anthousa could already feel the warm aura of the goddess surrounding her. The knowledge that Pamphile would be there for her with a caring smile and a shoulder to lean on made her feel even safer.

In this write-up, I work on the assumption that the figurine was a votive dedication to a goddess, specifically Aphrodite. Plank-figurines from Archaic Boeotia had a variety of usages, including household decoration, religious dedication, and funerary object (Higgins, 65). I chose to work with a votive function, and since the figurine is of a goddess, I assumed that it would likely be dedicated to a female deity. I researched temples, sanctuaries, and cults of goddesses in Boeotia and found a reference in Pausanias’ Description of Greece to a temple of Aphrodite in Tanagra (9.22.1). Since my piece was likely crafted in Tanagra, I chose this temple as the site where it would be dedicated. An Aphrodite-related setting also gave me the opportunity to further my project of exploring underrepresented groups, as Aphrodite was a patroness of sex workers (Pomeroy, 7). Since religious offering was a part of everyone’s daily life, and since there were no prohibitions against sex workers purchasing a votive figurine and dedicating it at a temple, I decided to make my votive petitioner a hetaira.

The social role of the hetaira was very complex, especially when compared to that of the average woman, and I wanted to explore the uniqueness of that position. In some ways, the lives of hetairai were more constrained, as they were under the sexual obligations of their clients, and could be slaves to a brothel-owner (Pomeroy, 88-89). In other ways, though, they had more social freedom than most women; for example, they were among the few women who could attend symposia (Garland, 148). They could not rely on the security of a marriage and only had access to the more informal pallake, but they were also not tied down to any single man (Garland, 83). Wealthier hetairai could buy their way out of slavery (had they been enslaved), achieve financial independence from an individual man, and exercise (relatively) more choice in terms of their clientele (Pomeroy, 92).

Two other fascinating but often under-examined aspects of the lives of ancient women, and particularly women in the sex industry, are contraceptives and abortion. I decided that my hetaira protagonist would be dedicating her votive as a way to secure Aphrodite’s protection in an abortion she was about to administer. Ancient medical texts suggest many techniques for performing an abortion, including the herbal concoction that my protagonist uses, which was recommended in Soranus’ Gynaecology (1.65). Soranus also offers various contraceptive techniques, including the insertion of “a lock of fine wool into the uterus” to prevent sperm from entering (1.61). The Greeks did not practice dissection of corpses and had little understanding of internal female anatomy (Garland, 167). Thus, it is easy to understand why contraceptives were often ineffectual and abortions often dangerous (Garland, 91). Asking the protection of a goddess, particularly a patroness of one’s profession, would have been a likely first step for women attempting to undergo these procedures.

Finally, I introduced the character of Pamphile, the priestess of Aphrodite, in this write- up. Pamphile will become more central in my re-use write-up, but for now, her relationship with the current protagonist provides me with an opportunity to explore how connections between women in a male-dominated society might have provided a source of solace and support. Pamphile’s friendship and well wishes are may not have been equally as encouraging as the perceived protection of the goddess, but I imagine that the comforting presence of another woman might have contributed to the reassuring effect of the spiritual connection with Aphrodite achieved through votive offering.

Re-use (Pamphile)

Pamphile wasn’t sure how, but as soon as she laid hands on the little clay votive figurine, she recognized it. Her friend Anthousa had dedicated it to the goddess almost a year ago. Pamphile’s heart swelled. She hadn’t seen her friend in months. Word around the agora had it that Anthousa had caught the eye of a wealthy Euboean passing through town on his way to Thebes. Perhaps she had left along with him. Pamphile dearly missed the companionship, and she smiled at this unexpected reminder of her friend. It was with great reluctance, then, that she took up a hand drill and began to bore a hole in the neck of the figurine.

This was all part of the preparations for an upcoming festival. Some of the plank figurines dedicated to the temple were to be strung up as decoration. She wasn’t quite sure why; this was just how it had been done for generations and generations, for as long as anyone in Tanagra could remember.

Distracted by thoughts of the festival and memories of Anthousa, Pamphile’s hand slipped. A web of cracks shot across the figurine’s neck. Pamphile lifted a hand to the figure’s head to assess the damage, and it fell clean off into her hand. The damage was too severe for the figurine to be hung, and it could no longer be displayed either. Pamphile grimaced. She had harmed the piece beyond any possible usefulness for the temple. Suddenly, a smile broke out across her face. The temple might have had no desire to retain the figurine, but Pamphile did. Even broken, it would be a reminder of her old friend.

Pamphile looked around. Technically, the statuette was still a votive, dedicated to the goddess. It was Aphrodite’s property and Pamphile could face punishment for taking it, both human and divine. Still, she felt that her connection with Aphrodite was strengthened through a lifetime of maintaining the goddess’ sanctuary and honoring her rites. She vowed to replace the votive with one of even greater value, a gesture that she hoped would avert any divine wrath. As for the human element, she felt confident that she could deal with it. With no one in sight, she slipped the two pieces into a fold of her chiton, cradling it delightedly as she continued her days’ work.

I was very intrigued by a repeated theme we explored in class, that of the emotional and symbolic value of objects. These are often couched in layers of meaning that may not be perceptible without biographical context. So in this portion of the object biography, I aimed to represent the importance that human relationships can impart on an object. I posited that my figurine served as a reminder for the priestess character, Pamphile, of her old friend Anthousa, who dedicated it. I also wanted to integrate an explanation for why the piece is broken along its neck. The situation I constructed, that Pamphile breaks the neck of the figurine while preparing it for reuse as a hanging decoration and surreptitiously takes it as a keepsake, brings these two considerations together.

In his description of a comparable Archaic Boeotian plank figurine from the Louvre collection, Violaine Jeammet mentions that Mycenaean predecessors of the plank figure type were sometimes found pierced through the neck (Jeammet, 4). He argues that this practice could have survived into the Archaic period, an explanation that would help clarify the broken neck of my piece. Unfortunately, I was unable to find further information on this practice, so Jeammet’s comment is the only evidence I have. My conjecture, then, as many other elements of my reuse narrative, is a tentative projection. Similarly, it would be very unusual for an Ancient Greek priestess to keep a broken votive as a personal possession. According to Beate Dignas, votive objects, even those that were old or damaged, “remained the property of the god and could not leave the sanctuary.” Such objects would typically be buried in pits on site, or the materials recycled to create new votives (Dignas). That being said, it is not impossible that a priest or priestess would take personal possession of a votive object, especially one that somehow lost its display value. My story seizes on this possibility, and presents an example of individual agency to deviate from normative behavior.

Pamphile’s motivation for this deviation is a deeply personal one, and it hinges on her investment in the figurine of a symbolic meaning superseding the original one. The reuse here ends up being the transformation of this figurine from religious dedication to sentimental keepsake. This was a common theme in our in-class discussion of our own personal objects, many of which derived either a partial or primary meaning from their status as a symbol of a relationship. As Ellen Swift writes, “psychological attachment and individual narratives or memories” are often major factors in an individual’s decision to retain, or ‘curate,’ an object, even after it has outlived its original use (168). For the vast majority of objects, these personal narratives are almost impossible to recover in an archaeological context. I wanted to speculate at one possible such narrative, and I took this occasion to do so. On a final note, this was also an excellent opportunity to feature a relationship between women, something that is typically not discussed in Classical literature and scholarship.

Metrodora (Deposition)

“Pamphile of Tanagra, Agapetos’ daughter, wife of Phokas. The handmaid and celebrated priestess of laughter-loving Aphrodite is buried here. She was beloved by her husband, Pamphile, fortunately chosen to watch over the seat of the goddess.”

So read the marker that Pamphile’s family erected at her grave. The funeral had been lavish affair for so modest a town as Tanagra. Pamphile’s faithful attention to the worship of Aphrodite had earned her the affection and reverence of the community, so nearly the whole polis had come out to see her off to the underworld in a glamorous procession. The ritual signs of lamentation performed by her family were echoed by members of the public as she was carried out of the city. Finally, her bier, furnished with gold, was set down by the ancestral tombs of her husband’s family, where she was cremated and urn put into the ground.

Metrodora, Pamphile’s sister-in-law, had been tasked with overseeing the purification of the household after the funeral. A widow herself, Metrodora was all too familiar with the process. Immediately after she heard of Pamphile’s death, Metrodora had set a bowl of water, drawn from the well at the center of town, outside the door. She had also strung up a bough of cypress in the doorway. Today, the day after the funeral, she was going to begin a full-scale purification of the house. The whole building was to be sprinkled with sea water, then further cleansed with hyssop. Finally, Metrodora would have to make a final sacrifice at the hearth. She had a good deal of work ahead of her.

As Metrodora entered the house, she dipped her hands in the bowl of water, a guarantee that she would bring none of the pollution of the grave into the home. She would have to remove most of Pamphile’s belongings before she could begin cleaning the women’s quarters. Most of her sister-in-law’s remaining possessions were everyday items, not ostentatious enough to merit their interment with a priestess. Many of them could also be repurposed in the household – after purification, of course – but one item was puzzling to Metrodora. While emptying a basket of Pamphile’s clothing, Metrodora noticed a small figurine in the shape of a woman, the head completely separated from the body. It must have been a reject from the temple, she assumed, but why would it have been in Pamphile’s personal belongings? Maybe she was going to have it repaired? Surely the goddess would want it even less, now that it had been tainted with the miasma of death. Anyway, the coroplasts’ workshops churned out plenty just like it. It wouldn’t be missed at all. Satisfied with her reasoning, Metrodora added the broken statuette to the discard pile. She would toss it on the refuse heap outside the house when her task was done.

I had originally intended my object to be buried along with Pamphile as a grave gift, a common usage for this type of figurine. However, after doing some research into the burials of Greek priestesses, I learned that they were often grand events characterized by opulent displays of wealth and influence. Literary representations tell of priestesses buried in impressive, public ceremonies, with grave goods made from costly materials, such as gold and silver (Breton Connelly, 223-224). Graves of holy women were also often marked by praiseful stelai and other monuments, two of which (as described in Joan Breton Connelly’s Portrait of a Priestess) served as the inspiration for my imagined grave marker for Pamphile (227, 235-237). Archaeological evidence seems to corroborate this picture, as graves that have been associated with priestesses have yielded a great deal of rich burial goods (Breton Connelly, 226). Thus, it is unlikely that a terracotta figurine of average quality, and a broken one at that, would have made its way into the assemblage of funerary materials.

With this in mind, I re-evaluated and decided that the deposition of the object would come about during the ritual cleansing of the household after a death in the family. I created the character of Metrodora, Pamphile’s sister-in-law, as the depositor of the object, as it was customarily the responsibility of female relatives to attend to customs relating to death (Garland, 174). Metrodora needed to be somehow detached from the household of a potential husband, otherwise she would not have been considered part of the same family unit as Pamphile. So, I decided that Metrodora would be a widow, and as such, would have returned to the household of her nearest male kin after her husband’s death. This also added a note of pathos to the narrative by representing Metrodora as someone with a particularly intimate knowledge of how to respond to death of a loved one.

I took some elements of the post-funeral purification process directly from Garland’s discussion, including the bowl of water outside the house and the cypress branch in the doorway (179). However, Garland did not go into further detail as to the rituals associated with purification of the household. A 5th Century law from the town of Iulis on the island of Kos provided more information. This law called for cleansing of the house on the day immediately following the funeral, to be accomplished by sprinkling sea water and hyssop throughout (von Prott and Ziehen, 260). I combined these two approaches and ultimately had Metrodora relocate Pamphile’s possessions during the cleaning process. Upon finding Pamphile’s keepsake, which, outside of its symbolic meaning to its late owner, would have appeared to hold little value or use, Metrodora decides that it is not worth salvaging and disposes of it. I imagine that it would have eventually ended up on one of the trash heaps that piled up in the streets of Greek cities and towns (Garland, 133).

Anastasios (Acquisition)

The year was 1904. Anastasios Collias strolled down the streets of Delphi, enjoying his leisurely walk home after a day’s work. He smiled as he thought of his wife awaiting him at home, hopefully setting the table for a hot meal. Suddenly, he felt a tap on his shoulder. He turned to see who was trying to catch his attention and found himself face to face with a young, mustachioed man.

“Might you know if there are any antiquities dealers nearby?” he asked, in somewhat choppy Greek.

“No, I don’t really know much about –”

Anastasios caught himself. It was true, he didn’t know much about the antiquities market. He found the whole affair rather too risky and he didn’t much enjoy dealing with Americans and Brits. However, he recalled that he had a little terracotta piece sitting around in a closet somewhere, a little figurine in the shape of a woman. The thing was broken and he had no particular attachment to it. Maybe he could sell it to this stranger. It wouldn’t hurt to have some extra drachmas around. He might even be able to use the profit to buy a little something nice.

The stranger was about to disappear when Anastasios spoke up again.

“I have an old statue at home. I could sell it to you. I’d charge you a reasonable price.”

“What a kind offer. I think I shall take you up on it.”

So Anastasios continued on his way home, now with the young stranger in tow. He learned that the man was American, a student of archeology in Rome. He asked Anastasios a few questions about the town, about his own life, but surprisingly few about the item he was about to purchase. If asked, Anastasios would have told of how he came by the little statue. He’d received it as a novelty gift from an old relative who lived in Schimatari, down by the Euboean Gulf coast. The old man had a whole sack full of them and he gave them out to his younger relations as if they were toys. Anastasios had received his at too old an age to find it particularly amusing as a plaything, and he was a little sore that out of all his siblings and cousins, he’d been given the broken piece. He remembered his mother asking where the old man had found the statues. She said she’d heard that grave robbery was widespread in the area, and that the government had even sent troops in to put a stop to it. The old man insisted that he’d come by the pieces honestly, while helping his neighbors dig a well, but neither Anastasios nor his mother were fully convinced. Perhaps that was why the young American was so reluctant to ask questions himself.

When they arrived at Anastasios’ house, the two men greeted Anastasios’ wife before retrieving the broken statue. The American pulled out a pair of spectacles and began to inspect the piece, while Anastasios and his wife traded hopeful glances. After what seemed a small eternity to the anxious couple, the young American removed his glasses.

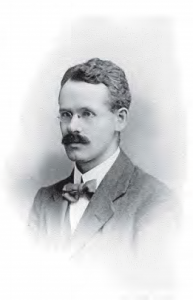

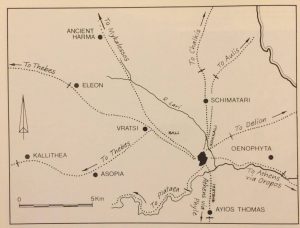

“I’ll take it.”

My primary objective in this write-up was to explain how my object made its way from Tanagra to Delphi. The former is where I hypothesize it was used and deposited, the latter where Albert William Van Buren, the Classics scholar who amassed the antiquities study collection now at Smith, indicates that he purchased it in 1904. I was largely inspired by John Boardman’s anecdote about a Boeotian villager who discovered terracotta figurines in his field and gave them to his children as toys (Boardman, 110-111). I thought it likely that my object might have been handed off across generations in a similar way, perhaps unearthed by someone who lived in the vicinity of Tanagra and then passed on as a gift to a younger family member who lived in Delphi. This younger individual could then sell the object to Van Buren, who was studying in Rome at the time as a fellow of the Archeological Institute of America (Geffcken, 41). These hypothetical figures became Anastasios and his old relative from Schimatari, a town located on one of the ancient roads radiating out of Tanagra. The town is among one of the early places where Tanagra figurines were re-discovered; Reynold Higgins speculates that the name “Schimatari” may even be derived from the Greek schema, which can refer to a figurine (Higgins, 29).

The major issue surrounding the re-discovery and acquisition of my object is that of legality. As of 1899, Greek law reserved “exclusive right of ownership of the state over all antiquities, moveable and immovable, found anywhere in Greece, even on private land” (Voudouri, 550). Thus, if the object was re-discovered any time after 1898, its ownership and re-sale by a private individual would be extremely suspect, and quite possibly difficult to achieve. I decided to stray away from this kind of black-market scenario, although not out of any faith in Van Buren’s moral code. It is clear from the account of Van Buren’s fellow collector David Hogarth, who describes how he and Van Buren reveled in the forbidden joys of looting, that ethical sourcing was not at issue for Van Buren’s milieu (Geffcken, 32). Indeed, even if my object had been re-discovered prior to 1899, it still may not have been under the most ethical of circumstances. From the early 19th Century, grave robbery was rampant in the area surrounding the ancient city of Tanagra (Higgins, 29). The problem was so severe that in 1873, the Greek authorities intervened, revoking excavation permits that had been illegally distributed to villagers and sending troops to the area (30).

Even though my object was not, at least in this hypothetical narrative, deposited in a grave, I wanted to address this part of Tanagra’s history, as well as Van Buren’s questionable collecting ethics. Thus, I had him exhibit an almost willfully ignorant attitude toward the provenance of my object in the narrative. He does not ask Anastasios how the piece was re-discovered, and Anastasios correctly guesses that this is because of the possibility that it had been obtained through grave robbery. This ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ approach was hardly atypical for collectors of Van Buren’s era, or, indeed, collectors today, as Colin Renfrew explains in Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership: The Ethical Crisis in Archaeology. This hypothesis could also help explain why there is such a lack of information about my object in the catalog of the Van Buren collection.

Bibliography

Boardman, John. “Archaeologists, Collectors, and Museums.” Whose Culture?: The Promise of Museums and the Debate over Antiquities. Ed. James Cuno. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009. 107-124. Print.

Boeotian Figurine. ca. 560-550 BCE. Smith College, Caverno Room (Northampton, Massachusetts, United States). ARTstor. Web. 30 Jan. 2017.

Breton Connelly, Joan. Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece. Princeton University Press, 2007.

Dignas, Beate. “A Day in the Life of a Greek Sanctuary.” A Companion to Greek Religion. Daniel Ogden, ed. Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Blackwell Reference Online.

Garland, Robert. Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks. 2nd ed., Hackett Publishing Company, 2008.

Geffcken, Katherine A. “The History of the Collection.” The Collection of Antiquities of the American Academy in Rome. Ed. Larissa Bonfante and Helen Nagy. Ann Arbor, MI: U of Michigan Press, 2015. 29-54. Print.

Higgins, Reynold. Tanagra and the Figurines. Princeton University Press, 1986.

Jeammet, Violaine, ed. Tanagras: Figurines for Life And Eternity: The Musée du Louvre’s Collection of Greek Figurines. Fundación Bancaja, 2010.

von Prott, Johann and Ludwig Ziehen, ed. Leges Graecorum Sacrae e Titulis Collectae: Ediderunt et Explanaverunt. Chicago: Ares Publishers, Inc., 1988.

Pausanias. Description of Greece, Volume IV: Books 8.22-10 (Arcadia, Boeotia, Phocis and Ozolian Locri). Trans., W. H. S. Jones. Loeb Classical Library 297, Harvard University Press, 1935.

Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. 2nd ed., Schocken Books Inc., 1995.

Renfrew, Colin. ITALIC Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership: The Ethical Crisis in Archaeology. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 2000. Print.

Soranus. “Gynaecology 1.24, 26, 24, 26, 39, 40, 60, 61, 62, 64.” Trans., O. Temkin. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation, 3rd ed. Ed. Mary R. Lefkowitz and Maureen B. Fant. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005

Swift, Ellen. “Object Biography, Re-use and Recycling in the Late to Post-Roman Transition Period and Beyond: Rings made from Romano-British Bracelets.” Britannia, Vol. 43 (2012), pp. 167-215.

Van Buren, Albert William. Inventory of Mr. A. W. Van Buren’s Archaeological Collection. Manuscript. 1908. Smith College Department of Classical Languages and Literatures.

Voudouri, Daphne. “Law and the Politics of the Past: Legal Protection of Cultural Heritage in Greece.” International Journal of Cultural Property 17.3 (2010): 547-68. Cambridge University Press. Web. 22 Apr. 2017.

Image Sources

Geffcken, Katherine A. “The History of the Collection.” The Collection of Antiquities of the American Academy in Rome. Ed. Larissa Bonfante and Helen Nagy. Ann Arbor, MI: U of Michigan Press, 2015. 29-54. Print.

Higgins, Reynold. Tanagra and the Figurines. Princeton University Press, 1986.

The J. Paul Getty Museum. “Attic Red-Figure Lekythos.” www.getty.edu. The J. Paul Getty Museum, n.d. Web. <http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/12025/circle-of-phiale-painter-attic-red-figure-lekythos-greek-attic-about-450-bc/>

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Terracotta funerary plaque.” www.metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-2017. Web. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/54.11.5/>

Wikimedia Commons, “Aphrodisias temple of aphrodite,” 2011, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aphrodisias_temple_of_aphrodite.JPG>.

Wikimedia Commons, “Boeotia ancient,” 2013, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boeotia_ancient-en.svg>.