This is an Etruscan fibula, a pin used to fasten clothing. It is made of bronze and dates from the 9th-8th centuries BCE. Since the fibula has no known archaeological context, this object biography is speculative, combining research and creative retelling to explore how people interacted with a particular object.

This is an Etruscan fibula, a pin used to fasten clothing. It is made of bronze and dates from the 9th-8th centuries BCE. Since the fibula has no known archaeological context, this object biography is speculative, combining research and creative retelling to explore how people interacted with a particular object.

Use the links below to navigate the stages of the narrative:

Manufacture

It was nearly impossible to tell time in the mine; the slaves working there were so deep underground that hardly any daylight reached them. An oil lamp sitting in a niche in the stone provided illumination. Sethre swung his pick into the rock, dislodging a chunk of copper ore. All around him, the sound of the other men’s picks hitting stone rang out. Judging by the size of the pile of ore he’d built up and by the soreness of his muscles, Sethre thought the day’s work was at least halfway done. He set down his pick and filled a basket with ore, then carried it out of the mine.

Sethre blinked as he stepped into the sunlight and added his ore to the pile on the ground. Soon the ore would be taken to Pupluna, he knew, and made into all kinds of metal objects. He wondered what fine things would be made from the ore he’d mined, knowing that as a slave he could never have bronze dishes or fibulae of his own. All he could look forward to was going home and eating a simple dinner.

◈◈◈

Arnth stoked the workshop’s furnace, shoveling charcoal into the fuel chamber. The fire had been burning since early in the morning, and he tried to judge whether it was hot enough to cast bronze. He’d been working there long enough to know when the fire was the right temperature, and he thought to himself that he’d made so many fibula he could probably cast one while blindfolded. He used tongs put smelted copper and tin in a crucible, watching as the metals gradually melted together. He called to another artisan to bring him a cast for a fibula. Carefully, Arnth poured the molten metal into the clay cast.

After allowing the metal to cool, Arnth broke off the clay to reveal the fibula. It had turned out well, he thought. He hammered the pin out into a coil and a long sharp point. Now the fibula was nearly done, and it was time for his favorite step, the decoration. Arnth neatly incised wide v-shaped lines on both sides of the bow, and thin horizontal lines across the top, middle, and bottom. He admired the rounded contours of the fibula and the elegant patterns on the surface. He hoped that the head of the workshop would notice how skilled at metalworking he had become, and allow him to start making larger and more interesting objects.

The limited information about the fibula in the Van Buren collection is that it is bronze, Etruscan, and from the 9th-8th centuries BCE. This provides a rough time and place for its production, but not much information about the techniques used. Based on what is known about Etruscan metallurgy, the fibula was probably made in a workshop using lost wax casting.

I chose Populonia (Pupluna or Fufluna in Etruscan) as the location where the fibula was made because the city was well-known for metallurgy, and archaeological excavations have revealed that copper smelting occurred there in the date range when the fibula was produced (Giardino 729). A recent excavation at Populonia revealed a large deposit composed mostly of iron slag, but with a bottom layer predominantly made of copper slag. The stratigraphy suggests that copper smelting in Populonia was prevalent before iron smelting began there. Charcoal fragments from the layer of copper slag date to the 8th century BCE (Cartocci et al. 386).

The slag’s chemical composition suggests that the copper ore was mined in the nearby district Campiglia Marittima (Cartocci et al. 386, Chiarantini et al. 1633). Etruscan mines typically followed mineral veins, and the shafts, which could reach depths of 120 meters, were connected by short horizontal galleries up to two meters high (Giardino 725). Miners used tools made of wood or flint until iron picks were introduced, and marks from such picks can be seen on Etruscan mine walls. Niches in the walls would have held oil lamps (Giardino 725). Miners probably carried ore out of the mines in leather or wicker containers on their backs, although these containers do not survive well in the archaeological record. It’s likely that many miners were slaves, which is why I chose to write about the miner Sethre as a slave who is bitter that he would be unable to acquire bronze items of his own.

After copper ore was mined, it would have had to be smelted and alloyed to make bronze. Smelting furnaces varied somewhat throughout Etruria, but they were typically made of stone and clay. A furnace found on the cliff edge at Populonia is rectangular, made of stone blocks held together with clay (Cartocci et al. 386). Furnaces found in the Val Fulcinaia (Valley of the Forges) near Populonia were round and built of sandstone with clay coating the interior, and covered with earth except for an opening in front (Modona 94). Nozzles called tuyeres positioned toward the bottom of the furnace controlled air flow. Charcoal from oak (Quercus) and tree heath (Erica arborea) have been found at furnace sites, suggesting they were common types of fuel for smelting and casting (Warden et al. 31).

Slag is a by-product of the smelting process, and the removal of molten slag makes smelting more efficient. The slag found at Populonia is flattened and has traces of sliding tracks that show it was in a semi-fluid state when it was released (Giardino 730). The shape of the slag cakes also suggests that slags were tapped into relatively large pits, a common practice in Copper and Bronze Age copper smelting processes (Chiarantini et al. 1633). I left smelting out of the narrative, however, because it would be overly technical and would likely have been performed by a different person than the one who cast and decorated the fibula.

Fibulae, like many other bronze objects, were typically made by lost-wax casting. In this method, a wax model was made and covered with clay, then the clay was fired to harden it into a mold and melt the wax out. Next molten bronze was poured into the mold, so it would take the shape of the original wax model. Clay molds made for lost wax casting have been found at several Etruscan sites associated with metallurgy (Giardino 733). Boat-shaped fibulae like the ones in the Van Buren collection were often cast hollow, by modeling wax over a clay core, then picking out the core through small holes after the fibula was cast (Cooney 91, Turfa 10). Once the bronze cooled, the mold could be removed and the pin and catchplate could be hammered out. Decoration could also be added at this stage by incision or engraving (Turfa 9). The linear designs on the fibulae in the Van Buren collection were incised into the bronze. The quality of the fibula and the fineness of the decoration suggest that it was made by an artisan with a fair amount of experience.

I gave the characters in the narrative names to emphasize their individuality. Sethre and Arnth are both Etruscan men’s names found in inscriptions. Since one is a slave and the other is an artisan, they have different experiences and different attitudes toward the fibula. Throughout my narrative, I try to humanize the people who created and used the fibula by imagining details about their lives that cannot be determined from the archaeological record.

Original Use

Ramtha looked proudly at the mantle she had just finished making and ran her hands over the wool cloth, admiring the fineness of the thread and the plaid pattern. It had taken many days of spinning and weaving, but it was a lovely replacement for her old, worn mantle. She removed the it from the loom and draped it over her the back of her linen chiton. Then she pinned the corners of the mantle to the shoulders of the chiton using her new pair of fibulae. She had traded a sheep for the fibulae, and she was pleased with the deal. The polished bronze of the fibulae stood out against the red cloth of the mantle. With these new items, Ramtha thought, she would be admired by other villagers.

She remembered that it was the day of the races. She put on her wooden shoes and called to her husband, who was outside tending the crops. Together they walked to the athletic field at the edge of Vetluna, where a crowd had already gathered to watch the games. Athletes stretched and horses stamped the ground while being harnessed to the chariots. One of Ramtha’s cousins greeted her and complimented her new mantle and fibulae. Then an official announced that the chariot race was about to begin. Four chariots lined up along the edge of the field, and when the judge blew a horn they set off. Ramtha and the other villagers clapped and cheered, watching as the drivers jostled and tried to outpace one another. After they had done seven laps around the field, the first chariot crossed the finish line, with the rest close behind. The winner was given a vase while the crowd applauded him. Ramtha smiled, enjoying the excitement of the race almost as much as the elegance of her new mantle.

The fibula in the Van Buren collection belongs to a category of objects with a clear purpose in Etruscan culture. They were used to fasten clothing, especially the mantles that most people wore over their chitons or tunics (Bonfante 16). Imagining the person who would have used the fibula is a bit more difficult. Certain styles of fibulae were associated with different genders. Serpentine and drago fibulae are typically found in men’s burials, and boat-shaped or leech-shaped fibulae are more often found in women’s burials, although it’s unclear what symbolic significance this differentiation may have had (Turfa 9, Caccioli 47). The fibula in the Van Buren collection is boat-shaped, so it most likely belonged to a woman. Judging from the quality of the fibula, the woman who owned it was probably of a relatively high status, although there was less class differentiation in the 8th century, when the fibula was probably made, than in the 7th century and later. It is difficult to determine the exact value of a fibula. There is no evidence of Etruscan currency prior to the 5th century BCE, well after the fibula was made, so someone would have had to trade for it. I speculated that a sheep could have been traded for a pair of fibulae.

Regardless of class, most Etruscan women would have spent a large portion of their time spinning and weaving. The common presence of implements like spindle whorls and loom weights in women’s graves suggests that spinning and weaving were associated with women, as they were in ancient Greece and Rome (Gleba 199). In the 8th century BCE, nearly all clothing would have been produced within the household, because textile specialization didn’t emerge until the 7th century (Gleba 201). Since the fibula was used with clothing and making clothing would have been a major part of an Etruscan woman’s work, I chose to incorporate this into the narrative by writing about Ramtha weaving herself a new mantle. A well-made mantle would have been a source of pride because of its beauty as well as the demonstration of its creator’s skill at spinning and weaving.

The typical clothing items for an Etruscan woman were chitons made out of either linen or wool and wool mantles. Wool thread was often dyed and mantles had checkered or plaid patterns woven into them, as shown in grave sculptures and noted by Roman writers (Turfa 9). In the 7th and 8th centuries BCE, the popular style of mantle for women was a narrow rectangle that hung down the back from both shoulders (Bonfante 16). Along with these primary items of clothing, Etruscans wore wooden or leather shoes and sometimes hats and jewelry. Etruscan shoes were particularly admired by the Greeks, and Aristophanes noted that many Athenian women wanted Etruscan sandals with gold laces (Bonfante 17).

Since mantles were outdoor wear, the woman would likely have been wearing her mantle and fibula to some event outside the home. Etruscan women had more rights and freedoms than their Greek and Roman counterparts, so it would not be unusual for them to be seen in public. Tomb paintings show them attending banquets and sporting events alongside men (Heurgon 143). For example, the Tomb of the Leopards and the Tomb of the Triclinium at Tarquinia depict men and women at symposia. Women were also given their own names not linked to their father’s or husband’s, and in many inscriptions an individual’s mother and father are both named, showing that both were socially important. Additionally, inscriptions on items like mirrors suggest that at least some women were literate (Warren 245). I thought the balance of domestic tasks like weaving and public activities in an Etruscan woman’s life would make an interesting narrative.

I decided to write about the woman attending an athletic competition, since that was a popular type of event in Etruria, often associated with religious festivals or funerals. Tomb paintings at Tarquinii depict foot races, chariot races, and boxing. Other games included discus and javelin throwing and high jump (Heurgon 168). These competitions most likely took place in open fields rather than in arenas. Racing chariots were made of wood, and they were drawn by either two or three horses (Thuillier 838). Winners were awarded vases. In this narrative of the fibula’s use, the fibula itself plays a relatively minor part, but I wanted to show how it fit into an Etruscan woman’s ordinary activities.

Reuse

Ramtha woke up feeling both excited and nervous. It was the day of her daughter Vela’s wedding, and there were many preparations to be made. Vela sat in a chair while Ramtha dressed her hair in a neat braid, fastened on her earrings, and put perfumed oils on her. Ramtha’s fingers trembled as she pinned her daughter’s mantle with the fibula that used to be her own, thinking about how much both of their lives would change. She knew she should be happy; it was a good marriage to a man named Larce who owned a large farm. But he lived outside Vetluna, too far away to visit often. Ramtha worried that Vela would feel lonely. At least the fibula would be a reminder of the family she came from.

Together they walked to the temple, where other relatives were gathering. Vela and Larce stood together with the priest under a ceremonial blanket. The priest conducted the ritual, reciting prayers to Uni and Turan for a happy marriage and the birth of healthy children. Then it was time for the divination. A slave led a sheep to the altar and sacrificed it, and the haruspex examined its liver, tilting his head and staring intently. Ramtha watched his face anxiously until he announced that the couple had a promising future. Vela glanced at her mother with an expression of relief.

Finally it was time for the couple to go to their new home. They sat in a cart pulled by a horse and the rest of the group walked alongside them. In Ramtha’s last glimpse of her daughter, she was stepping through the doorway of Larce’s hut. Ramtha hoped Vela would continue to wear the fibula and that it would make her think of her parents.

I decided the Van Buren fibula would be reused during a young woman’s marriage, as a gift from her mother to mark her entrance into a new stage of her life. She would likely have worn the fibula on her mantle during the wedding and on the way to her new home.

Most evidence about Etruscan weddings comes from grave goods, which offer a rather limited perspective. A relief from Chiusi depicts a wedding ceremony in which a bride, groom, and priest stand under a canopy or blanket (Bonfante “Etruscan Couples” 160). A textile covering husband and wife is also used as a symbol of marriage in other works, such as sarcophagi where a man’s mantle is draped over his wife. A plaque from a residence at Poggio Civitate depicts a woman riding in a carriage, which may represent a bridal party approaching the bride’s new home (Bonfante “Etruscan Couples” 160). This would be similar to ancient Greek and Roman weddings, which included a procession to the married couple’s new home.

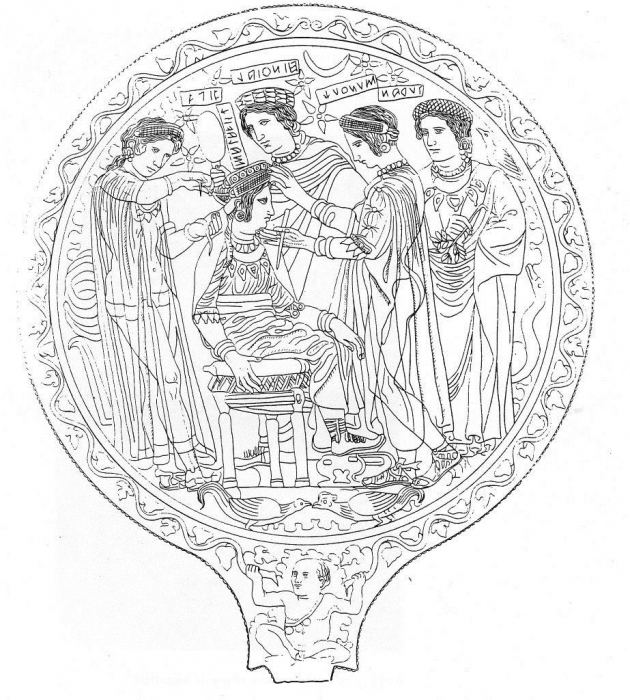

Another source of information about Etruscan weddings is engraved mirrors. However, Etruscan mirrors date from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE, considerably later than the period in which the Van Buren fibula was made and used. However, mirrors can still give a general idea of what earlier weddings may have involved. Mirrors often feature mythological scenes emphasizing themes of love and marriage. For example, on one mirror Turan, the goddess of love, brings together figures labeled as Paris and Helen. The link between mirrors and weddings is strengthened by the fact that mirrors were sometimes given as wedding gifts. A mirror depicting Peleus and Thetis bears the inscription mi malena larθia puruhenas, which has been translated “I am the wedding gift of Larth Purubena [to his bride]” (Bonfante “Etruscan Mirrors”).

A common type of image on mirrors is women adorning themselves, and it has been suggested that these scenes specifically depict women preparing for weddings (Bonfante “Etruscan Mirrors”). On one mirror, the goddesses Menrva and Turan adorn Uni, the goddess of marriage, who is preparing for her own wedding. Bathing was also part of the preparation for marriage, and some mirrors depict men and women with strigils and oil flasks. Although the details of wedding preparation might have differed somewhat in the 8th century BCE when the fibula was used, weddings most likely involved adornment of the bride. In my narrative, Ramtha helps her daughter prepare for the wedding by applying perfumed oils and putting on jewelry.

Prophecy was also an element of wedding rituals, and some objects represent the way it was practiced. For example, several mirrors feature a similar scene in which a bride and groom consult an oracle seated on the right, who writes down the prophecy given by the head of Orpheus. Another mirror shows a man and woman labeled Fasia and Mexio embracing, while a figure labeled Ceisia Loucilia interprets a prophecy, as stated in the inscription (Bonfante “Etruscan Mirrors”). Acts of divination associated with marriage are also suggested by a house model from Chiusi dated to 500 BCE, which has a relief sculpture on one side depicting a haruspex walking ahead of a bride and groom (Busby 72). The haruspex may either have made his divination before the wedding ceremony or just before the bride and groom entered their new home.

Although it seems likely that divination was part of wedding rituals, the specific way it was performed remains unclear. Common methods of divination included observing thunder and lightning, watching flocks of birds, and analyzing an animal’s entrails. A Greek translation of an Etruscan thunder (brontoscopic) calendar gives the meaning of thunder on each day of the year. For example, it states that if there is thunder on July 13th, “there will appear the most poisonous reptiles” (Turfa 183). The Roman writer Servius noted that lighting was observed to make predictions related to weddings.

Divination from the entrails of sacrificed animals was also common. A bronze model of a sheep’s liver found near Piacenza is divided into forty-two sections with the name of one or more gods written in each (Bonfante “Etruscan Inscriptions” 11). A mark on a real liver would be linked to the god or gods named on the corresponding section of the model, allowing a priest to predict the future. On one mirror, a figure labeled Pava Tarchies wears the hat of a priest and has his left leg raised in the ritual pose for prophecy as he examines a liver held in his left hand (de Grummond 540). I decided that since there was unlikely to be lightning the day of or shortly before the wedding, it would be more likely that the haruspex performed divination from entrails.

The wedding in my narrative is my best inference about what an 8th century BCE Etruscan wedding would have involved, from the personal adornment beforehand to the divination and the procession to the couple’s new home. Since it’s impossible to know exactly what the ceremony included, I guessed that there would be prayers to Uni and Turan, the goddesses of marriage and love, respectively. The main idea underlying the narrative is the emotional bond between mother and daughter that is expressed through the gift of the fibula, and how that bond remains even when the daughter gets married and moves away.

Deposition

Larce prepared to go to the necropolis, but he could hardly bear the thought of seeing anyone. His wife Vela had died in childbirth and now he had to bury her. The baby boy, her second child, had lived. But how would he grow up without his mother? Who would cook and weave the family’s clothes? Without Vela, Larce didn’t know what to do.

He rode his horse to the necropolis, accompanied by the other mourners, and they gathered at his family’s group of tombs. Vela’s cremated remains were in an urn with a bowl covering the top. Larce knelt and wrapped her plaid mantle around the urn, and fastened it with her fibula. It was fitting that the items she had worn nearly every day would stay with her in death. He lowered the urn into the tomb, along with a few of Vela’s spindle whorls and an amphora.

After the grave goods had been arranged, the mourners recited prayers and offered Vela’s remains a symbolic meal while a musician played a double aulos. Then they sealed the tomb and ate the banquet that had been prepared for them. Larce made an effort to talk to the other guests, but he couldn’t focus on the conversation. He thought of Vela and had to hold back tears, telling himself that at least a proper burial would help her move to the afterlife.

The fibula in the Van Buren collection has no recorded archaeological context, so my narrative about its deposition is speculative. Placement in a burial is the most likely form of deposition for the fibula, because most Etruscan artifacts have been found in tombs and fibulae are commonly found in burials from all periods of Etruscan culture. Deposition in a tomb would also explain why the fibula is in fairly good condition. In the reuse section I said the fibula belonged to a young woman after it was given to her for her wedding, so I decided that it would be buried with her after she died in childbirth. That would not have been uncommon in the Etruscan world, and I thought it would demonstrate the dangers women faced in everyday life, as well as the way objects were used in funerary rituals and grieving practices.

In the 9th century BCE, around the time when the fibula was made, cremation was much more common than inhumation (Bartoloni 84). Cremated remains were buried in impasto (coarse-grained ceramic) urns. The urns were typically biconical, and could have one or two handles as well as incised decoration. A very small proportion of urns were made in the shape of a hut, mostly in coastal and southern interior Etruria. (Bartoloni 86). However, there is no indication that hut urns marked status, since both kinds of urn were usually accompanied by the same types and amounts of grave goods (Bartoloni 86).

Urns were usually covered with black impasto bowls, or sometimes ceramic helmets for men’s burials. They were dressed in garments, fibulae, and pendants or had clothes and jewelry painted on. Therefore urns were most likely symbolic representations of the deceased’s body, providing a focal point for funerary rituals (Caccioli 53). The garments in which the urns were clothed do not survive, but the fibulae do. The Van Buren fibula was likely used to fasten clothes on an urn and then was preserved in the tomb.

In 9th century BCE burials, grave goods were fairly limited; they included spindle whorls for females, razors for males, and fibulae for both sexes. Weapons and additional vessels were rare (Bartoloni 85). The equality of grave goods suggests that funerary ideology stressed equal burials even if people were socially differentiated. Grave goods distinguished individuals of different sexes before they distinguished social classes. In the 8th century BCE, economic differentiation became more apparent in tombs. Some people were buried with more and finer grave goods. Men were often buried with a razor, shield, and helmet, and sometimes weapons like a sword or spear. Women were buried with impasto spindle whorls, loom weights, jewelry, and sometimes also spindles and distaffs made of bronze (Bartoloni 89). Both sexes continued to be buried with fibulae and impasto ceramic objects. I decided it would be plausible for the woman in my narrative to be buried with a fibula, spindle whorls, and an impasto amphora. The spindle whorls might have been chosen to reflect her skill at spinning and weaving, since those were important tasks that could be a source of prestige for women.

Etruscans buried the dead in necropoleis, which were typically located on opposite sides of a town, most often in the north and south but sometimes in the east and west. Within a necropolis, tombs were arranged into groups, probably by family. Grave goods tend to be similar in each group, suggesting that the individuals were of equal status or at least were given equal burials (Bartoloni 89).

Funerals often involved music, athletic competitions, and a banquet. Most of the evidence about these elements of the ritual come from tomb paintings created a few centuries after the Van Buren fibula was made and used. However, earlier funerals probably involved similar practices. Funerals likely included symbolic meals for the deceased as well as banquets for the mourners (Caccioli 54). 7th century BCE tombs at Caere contain numerous vessels, some with organic material still in them, suggesting that banquets may have taken place in the tombs (Pieraccini 39). In contrast, tomb paintings at Tarquinia depicting banquets imply that they took place just outside the tombs, under a tent or canopy. Regardless of where exactly banquets were held, they likely served to demonstrate the status of the deceased’s family and strengthen social ties.

Music also played a role in funerary rituals. Homage sung for the dead is frequently depicted in tombs (Torelli 152). Instruments such as the double aulos and lyre were also played, and they sometimes accompanied dancing. A tomb painting from the Tomba del Morto at Tarquinia depicts five figures around a funeral bier, while one figure plays a double aulos (Meyer-Baer 230). I incorporated a banquet and a musician into my narrative of the funeral, since those are plausible elements of an 8th century BCE Etruscan funeral.

After its use and reuse, the Van Buren fibula was most likely placed in a tomb, preserving it in fairly good condition for millennia. Objects made for the living often ended up with the dead, serving a new symbolic purpose. My narrative includes the range of activities involved in a funeral, as well as the way the deceased woman’s husband felt, to demonstrate the ways Etruscans reacted to death.

Acquisition

Giulio was walking through his vineyard, checking how large the grapes had gotten, when he noticed pot sherds in the soil. This wasn’t so unusual; he’d grown up seeing remnants of ancient people, knowing that their tombs were below modern farms and roads. He knelt down and scooped some soil away with his hand, and then saw a glint of metal. After digging a bit further, he could tell that it was some kind of pin. Giulio had never seen a metal artifact that intact. He picked it up and slipped it into his pocket, wondering how much money he might be able to get for it.

A few days later, when he’d gone into town, he offered the pin to a man who he’d heard dealt in antiquities. The man looked eagerly at it, turning it over in his hands. He gave Giulio four lire for the artifact, and although Giulio didn’t know if that price was good, he was glad to have the extra money.

◈◈◈

Richard Norton was on his way home from lunch one Saturday in 1903 when he decided to stop by the Jandolo brothers’ antiquities shop. He’d been there many times, and he always enjoyed looking through the jumble of vases, statues, and coins. On one shelf he saw an Etruscan fibula with incised decoration, and he decided on a whim to buy it. As Norton paid for the fibula, he wondered just how old it was and where it had come from. Regardless of its provenance, it would make a nice addition to his personal collection.

A few years later, Norton’s collection had grown quite large. He sorted through the antiquities and decided to give some to the American School of Classical Studies in Rome. But a few that the School had no need for, he gave to the lecturer Albert William Van Buren. The young man was happy to have the fibula, and Norton didn’t miss it.

There’s very little documentation regarding the fibulae in the Van Buren collection. It’s unknown when they were acquired, who acquired them, or whether the three fibulae were acquired together. Given this lack of information, I did my best to construct a plausible history for the way this fibula was found and brought to Smith College.

In my narrative, the fibula was found by an Italian farmer on his land. I thought it was more likely that he casually discovered it than that it was taken as part of an organized looting effort, especially since the fibula is from a 9th or 8th century BCE, and therefore probably not very elaborate, burial. The farmer could have then sold the fibula to a dealer for a modest price. Digging for archaeological objects and owning them without official permission has been illegal in Italy since 1909, and in 1939 Italy claimed all cultural property more than 50 years old (Rose-Greenland). However, the discovery of the fibula likely predates those laws, and if not, it is not rare or valuable enough that the government would try to prevent its sale.

Since the fibula is not mentioned in Van Buren’s catalog, I looked for comparable acquisitions by Smith and the rest of the five colleges to try to determine when it might have been purchased or donated. Amherst has several 8th century BCE Roman fibulae acquired in 1946; three were from the Latin department, and four were purchased by the museum. Mount Holyoke has a 7th century BCE Italic fibula purchased in 1943. The 1940s appear to have been a popular time to collect fibulae, perhaps because the colleges were trying to expand their classical collections, and fibulae were relatively inexpensive during and shortly after World War II. The Smith College Museum of Art has a fragment of an Etruscan strigil given by Charles Loeser in 1920 but very few other Etruscan metal objects, and no fibulae at all. It seems unlikely that the fibula in the Van Buren collection was acquired in the 1940s like the fibulae at the other colleges, considering that there’s no documentation of it. That suggests either the fibula was added to Van Buren’s collection before it came to Smith, or that it was contributed by a Smith College Classics professor in the early 20th century.

I decided that Richard Norton, the director of the American School of Classical Studies in Rome, could have purchased the fibula and given it to Van Buren, who was a lecturer and librarian at the school. It seemed plausible because Norton was living in Rome, relatively close to where the fibula was buried and found, and he had a connection to Van Buren. Norton purchased several artworks and antiquities from dealers including the Jandolo brothers and G. Tavazzi (Geffcken 25). In my narrative, he purchased the fibula from Antonio and Alessandro Jandolo’s dealership sometime around 1903, and gave it to Van Buren a few years later, shortly before Van Buren took his collection to Yale in 1906. An Italian law passed in July 1902 prohibited the exportation of antiquities for a period of two years after they were found, so the sequence of events I propose would be in accordance with the law (Loria 633).

Norton died of meningitis in 1918 (Geffcken 22). Van Buren’s collection remained at Yale until 1925, when F. Warren Wright from the Smith College Latin department purchased it for $100 (Bradbury). Since 1925 the Van Buren collection, including the fibula, has been at Smith, but without complete records for some of the artifacts. Although the acquisition of the fibula is much more recent than the other stages of its history, there is still a great deal of uncertainty about who acquired it and when. My narrative is just one possibility among many.

Bibliography

Manufacture

Cartocci et al. “Study of a Metallurgical Site in Tuscany (Italy) by radiocarbon dating.” Accelerator Mass Spectrometry — Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, special issue of Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, vol. 259, no. 1, 2007, pp. 384-387.

Chiarantini et al. “Copper production at Baratti (Populonia, southern Tuscany) in the early Etruscan period (9th-8th centuries BC).” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 36, no. 7, 2009, pp. 1626-1636.

Cooney, John D. “Variations on a Theme.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Vol. 58, No. 3, 1971, pp. 91-95.

Giardino, Claudio. “Villanovan and Etruscan Mining and Metallurgy.” The Etruscan World, edited by Jean MacIntosh Turfa, Routledge, 2014, pp. 721-737.

Modona, Aldo Neppi. “Etruscan Metallurgy.” Scientific American, vol. 193, no. 5, 1955, pp. 90-98.

Turfa, Jean MacIntosh. “Early Etruscans: A Glimpse of Iron Age and Orientalizing Italy through Artifacts.” Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005, pp. 3-12.

Warden, P.G. et al. “Copper and Iron Production at Poggio Civitate (Murlo).” Expedition Magazine vol. 25, no. 1, 1982, pp. 26-35.

Original Use

Bonfante, Larissa. “The Language of Dress: Etruscan Influences.” Archaeology, vol. 31, no. 1, 1978, pp. 14-26.

Caccioli, David A. Monumenta Graeca et Romana Ser.: The Villanovan, Etruscan, and Hellenistic Collections in the Detroit Institute of Arts. Brill, 2009.

Gleba, Margarita. “Coda: Textile Production in its Social Context.” Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy, Oxbow Books, 2008.

Heurgon, Jacques. Daily Life of the Etruscans. Translated by James Kirkup, The Macmillan Company, 1964.

Thuillier, Jean-Paul. “Etruscan Spectacles: Theater and Sport.” The Etruscan World, edited by Jean Macintosh Turfa, Routledge, 2014, pp. 831-840.

Turfa, Jean MacIntosh. “Daily Life in Etruria: The Accouterments of War and Peace, Work and Home.” Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Warren, Larissa Bonfante. “Etruscan Women: A Question of Interpretation.” Archaeology, vol. 26, no. 4, 1973, pp. 242-249.

Reuse

Bonfante, Larissa. “Etruscan Couples and Their Aristocratic Society.” Women’s Studies, vol. 8, no. 1/2, Jan. 1981, p. 157.

Bonfante, Larissa. “Etruscan Mirrors and the Grave.” Publications de l’École française de Rome, 2015.

Bonfante, Larissa. “Etruscan Inscriptions and Etruscan Religion.” Religion of the Etruscans, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon, University of Texas Press, 2006, pp. 9-26.

Busby, Kimberly Sue. The Temple Terracottas of Etruscan Orvieto: A Vision of the Underworld in the Art and Cult of Ancient Volsinii. 2007

de Grummond, Nancy T. “Haruspicy and Augury: Sources and Procedures.” The Etruscan World, edited by Jean Macintosh Turfa, Routledge, 2014, pp. 539-556.

Turfa, Jean MacIntosh. “The Etruscan Brontoscopic Calendar.” Religion of the Etruscans, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon, University of Texas Press, 2006, pp. 173-190.

Deposition

Bartoloni, Gilda. “The Villanovan Culture: At the Beginning of Etruscan History.” The Etruscan World, edited by Jean Macintosh Turfa, Routledge, 2014, pp. 79-98.

Caccioli, David A. “The Funerary Function of Villanovan and Etruscan Ceramics in the Detroit Institute of Arts.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol. 85, no. 1/4, 2011, pp. 52–61.

Meyer-Baer, Kathi. “Music as a Symbol of Death in Antiquity.” Music of the Spheres and the Dance of Death: Studies in Musical Iconology, Princeton University Press, 1970, pp. 224–241.

Pieraccini, Lisa. “Families, Feasting, and Funerals: Funerary Ritual at Ancient Caere.” Etruscan Studies, vol. 7 , 2000, pp. 35-49.

Torelli, Mario. “Funera Tusca: Reality and Representation in Archaic Tarquinian Painting.” Studies in the History of Art, vol. 56, 1999, pp. 146–161.

Acquisition

Bradbury, Scott. “History.” Van Buren Antiquities Collection, 15 March 2011, www.smith.edu/ classics/vanburen/history.php. Accessed 23 April 2017.

Geffcken, Katherine. “The History of the Collection.” The Collection of Antiquities of the American Academy in Rome, edited by Larissa Bonfante and Helen Nagy, University of Michigan Press, 2015, pp. 21-78.

Loria, Achille. “Recent Italian Legislation on Works of Art and Antiquity.” The Economic Journal, vol. 13, no. 52, 1903, pp. 632-635.

Rose-Greenland, Fiona. “Looters, Collectors, and a Passion for Antiquities at the Margins of Italian Society.” 2014. ccs.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Working%20Papers/WP2%20ROSE%20GREENLAND.pdf

Image Credits

Fibula: Van Buren Collection, Smith College; photo by Renee Klann, https://sites.smith.edu/image-repository/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/ninja-forms/%202017-04-17-331-fibula3.jpg

Map: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Etruscan_civilization_map.png

Fibula side view: Van Buren Collection, Smith College; photo by Renee Klann

Statuette: Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/249222

Tomb of the Leopards: photo by AIMare, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tarquinia_Tomb_of_the_Leopards.jpg

Mirror: British Museum, http://books.openedition.org/efr/2741

Model of liver: IBC Multimedia, http://www.ibcmultimedia.it/contenuti/il-fegato-etrusco-di-piacenza/

Funerary urn: National Etruscan Museum, Florence; photo by Sailko, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vaso_biconico_da_chiusi,_poggio_renzo,_IX-VIII_sec._ac..JPG

Spindle whorls: Agora Auctions, https://agoraauctions.com/listing/viewdetail/25179

Bronze Italic fibula: Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=all&t=objects&type=all&f=&s=fibula&record=13

Via Margutta: Roma Sparita, photo by Giacomo Bront, https://www.romasparita.eu/foto-roma-sparita/37906/via-margutta-british-academy-of-arts