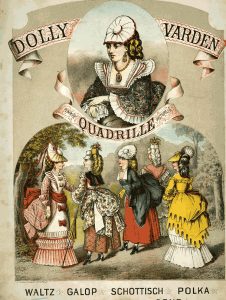

The Philadelphia Dolly Vardens

The Philadelphia Dolly Vardens were two different, concurrent African-American women’s baseball teams formed in 1883.1 Earlier women’s teams had existed since the 1860s, but the Dolly Vardens were the first to be paid and achieve popularity, playing in calico dresses and red jockey caps.2 Unfortunately, these teams were seen primarily as a novelty circus act, though they did provide avenues for women to make a living playing baseball. Women were discouraged but technically able to play professionally, both on women’s and men’s teams, until the 1930s, but African-American women saw few opportunities again outside of the men’s Negro Leagues until the 1960s, due to the segregated nature of organizations like the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

The Philadelphia Dolly Vardens were two different, concurrent African-American women’s baseball teams formed in 1883.1 Earlier women’s teams had existed since the 1860s, but the Dolly Vardens were the first to be paid and achieve popularity, playing in calico dresses and red jockey caps.2 Unfortunately, these teams were seen primarily as a novelty circus act, though they did provide avenues for women to make a living playing baseball. Women were discouraged but technically able to play professionally, both on women’s and men’s teams, until the 1930s, but African-American women saw few opportunities again outside of the men’s Negro Leagues until the 1960s, due to the segregated nature of organizations like the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

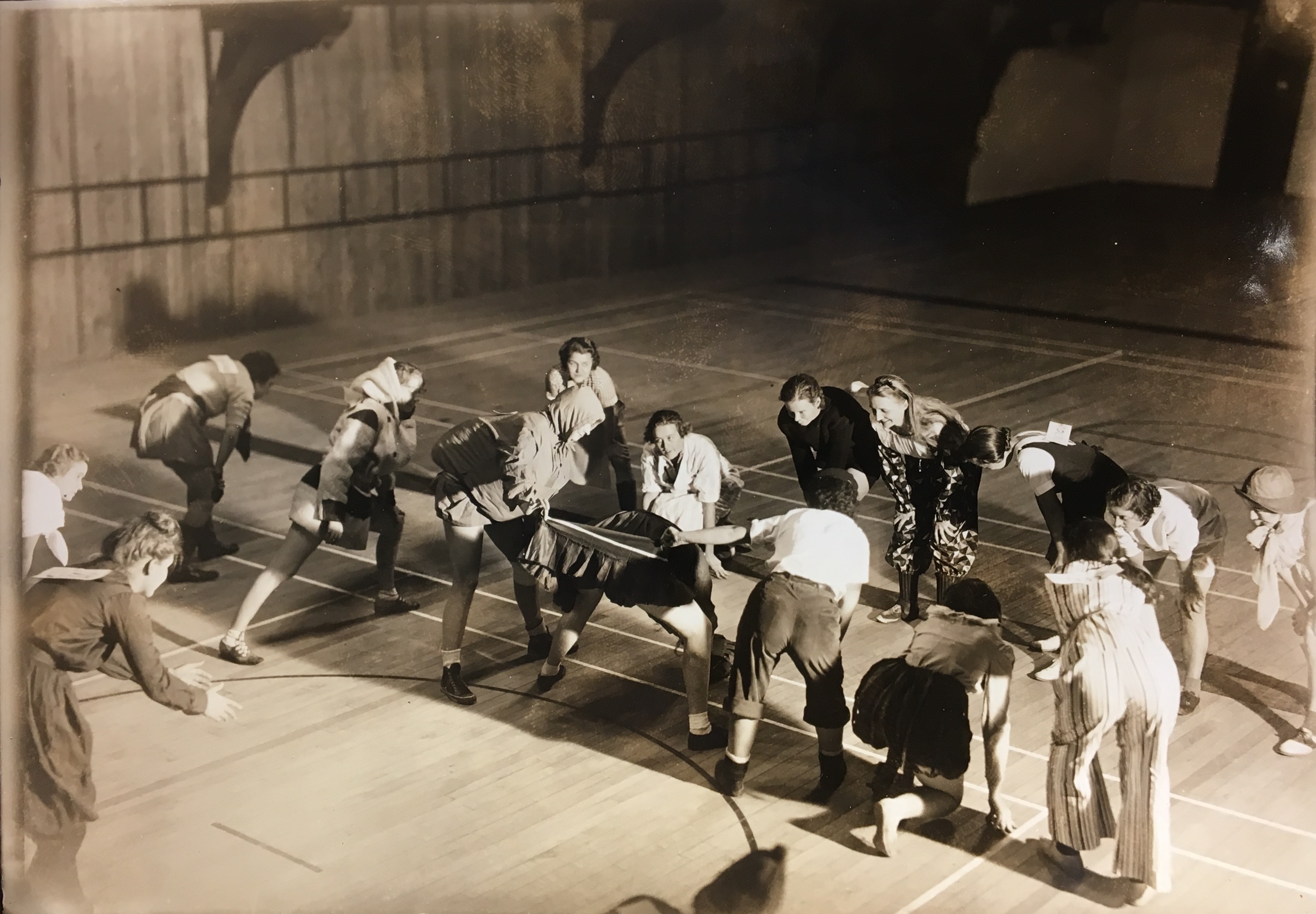

Senda Berenson

Born in 1868 in Vilna, Lithuania, Berenson was trained at the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics and hired by Smith College in 1892, where she modified the newly invented game of basketball for women, and organized the first women’s basketball game in 1893.3 Blending gymnastics with some of the earliest team sports for women, Berenson believed she could improve the physical health and thus workplace opportunities of her students, and sought to teach as wide a range of activities to as many young women as possible. She became one of the first two women inducted into the National Basketball Hall of Fame in 1985, and was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2006.

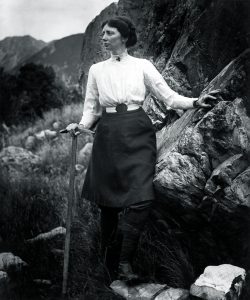

Emmeline Freda du Faur

Du Faur was a pioneering mountaineer in New Zealand, becoming the first woman to summit Mt Cook in 1910, with the fastest time by any climber to that date.4 Though she eschewed skirts when climbing and chose to wear pants instead, she enjoyed appearing as feminine as possible after her major climbs to “disconcert critics and upset existing stereotypes of physically active women.” She retired from climbing to move to England to live with her partner, Muriel Cadogan, where she published her book, The Conquest of Mt. Cook, in 1914.

Lucy Diggs Slowe

Lucy Diggs Slowe was born in 1885, and became the first African-American woman to win a major spots title (in any sport) when she won the American Tennis Association’s first women’s competition at the national tournament in 1917. However, her athletic career was a footnote to her prolific life in academia and college administration. Graduating second in her high school class, Slowe attended Howard University and became one of the original founders of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, the first sorority founded by African-American women. She went on to earn her M.A. from Columbia University, founded the first junior high school in Washington, D.C. in 1919, and became the first Dean of Women at Howard University in 1922, a position she held until her death.5

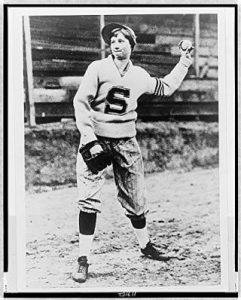

Virne “Jackie” Mitchell

Jackie Mitchell was a left-handed pitcher for the Chattanooga Lookouts minor league baseball team in 1931, and became best known at 17 years old for striking out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in succession. Her feat came 32 years into the unofficial ban of women from professional baseball, and resulted in the termination of her contract by the league commissioner at the time, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Other women who followed in her footsteps saw similar measures taken by Major League Baseball to discourage them from playing, until women were officially banned in 1952. Mitchell’s career continued for six more years with barnstormer teams until she reportedly grew tired of being seen as a circus act and quit baseball at age 23.

Joe Carstairs

Born Marion Barbara Carstairs in London in 1900, Joe was the wealthy heir to the Standard Oil fortune. She began by racing cars but preferred boats, becoming well-known in the European racing scene for not only her racing skill, but her lavish spending habits, “boyish” appearance, and long string of affairs with well-known actresses and heiresses of the time. In the racing world, she went on to win the won the Duke of York’s Trophy, the Royal Motor Yacht Club’s international race, and the Lucina Cup,6 and set world records for speedboat racing before leaving Europe entirely to relocate to Whale Cay, and island she purchased in the Bahamas.7

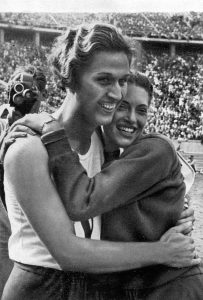

Helen Stephens

Helen Stephens won two gold medals as a teenager for her performance in the 1936 Olympics, at which she set world, Olympic, and American records for running, broad jump, and discus.8 She returned to her hometown of Fulton, Missouri after the games, where she completed a college education and went on to play professional basketball with the All-American Red Heads. Stephens became the first woman to create, own, and manage a semi-pro basketball team in 1938, when she created the Helen Stephens Olympic Co-Eds, which competed until 1952. The team took a brief hiatus for World War II, during which Stephens worked at an aircraft plant in St. Louis before enlisting in the Women’s Reserves of the US Marines. Her career in defense continued after the war as well, when she became a research librarian for the Defense Mapping Agency Aerospace Center in St. Louis. She remained a lifelong participant and activist in sport, and at age sixty-eight, she competed in the Senior Olympics, and finished the 100 meter dash just four seconds slower than her teenage record time.9

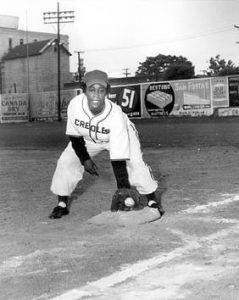

Marcenia Lyle “Toni” Stone

Described by the NLBPA as, “the best ballplayer you’ve never heard of,”10 Toni Stone was the first woman to ever play a full season in professional baseball and the first woman ever in the Negro Leagues. She began her career with the San Francisco Sea Lions of the West Coast Negro Baseball League, but left for other teams when she did not receive her promised pay. Her career spanned four teams and included taking over second base on the Indianapolis Clowns from Hank Aaron and a hit off of baseball legend Satchel Paige. Her final season was played in 1954 with the Kansas City Monarchs, which she described as “hell” due to the undisguised hatred she experienced from teammates. She retired to Oakland due to a lack of playing time, and was inducted into the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1993.

Described by the NLBPA as, “the best ballplayer you’ve never heard of,”10 Toni Stone was the first woman to ever play a full season in professional baseball and the first woman ever in the Negro Leagues. She began her career with the San Francisco Sea Lions of the West Coast Negro Baseball League, but left for other teams when she did not receive her promised pay. Her career spanned four teams and included taking over second base on the Indianapolis Clowns from Hank Aaron and a hit off of baseball legend Satchel Paige. Her final season was played in 1954 with the Kansas City Monarchs, which she described as “hell” due to the undisguised hatred she experienced from teammates. She retired to Oakland due to a lack of playing time, and was inducted into the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1993.

Althea Gibson

Althea Gibson played golf and tennis, and became the first Black athlete to cross the color line in international tennis. In 1950, at 23 years old, she was permitted to participate in US National Championships, becoming the first Black athlete of any gender to do so, and earned the same distinction at Wimbledon; she later won both tournaments in both 1957 and 1958.11 Including six doubles titles, she won an impressive 11 Grand Slam titles over the course of her career. Despite her fame and success, she was still routinely denied rooms at hotels, but attempted to avoid casting herself as a representative of the Black tennis community and continued to play and coach tennis for her love of the game. However, athletes who followed in her footsteps, including Billie Jean King, credit her efforts for blazing a trail for Black athletes and visibility of tennis as a sport.

Althea Gibson played golf and tennis, and became the first Black athlete to cross the color line in international tennis. In 1950, at 23 years old, she was permitted to participate in US National Championships, becoming the first Black athlete of any gender to do so, and earned the same distinction at Wimbledon; she later won both tournaments in both 1957 and 1958.11 Including six doubles titles, she won an impressive 11 Grand Slam titles over the course of her career. Despite her fame and success, she was still routinely denied rooms at hotels, but attempted to avoid casting herself as a representative of the Black tennis community and continued to play and coach tennis for her love of the game. However, athletes who followed in her footsteps, including Billie Jean King, credit her efforts for blazing a trail for Black athletes and visibility of tennis as a sport.

- Weeks, Linton. “Baseball in skirts, 19th century style.” NPR, July 12, 2015.

- Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1883.

- Senda Berenson papers, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00037, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

- Langton, Graham. ‘Du Faur, Emmeline Freda’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, December 2005. https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3d17/du-faur-emmeline-freda.

- Notable Columbians Scholarly Projects. “Lucy Diggs Slowe.” Columbia University, 2019. https://blackhistory.news.columbia.edu/people/lucy-diggs-slowe.

- Hogan, Heather. “22 Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trans Woman Athletes Who Changed the Game.” October 31, 2017. https://www.autostraddle.com/22-lesbian-bisexual-and-trans-women-athletes-who-changed-the-game-399393/.

- Cheshire, Tom. “Boss of the Bahamas: Joe Carstairs.” The Rake, June 2016. https://therake.com/stories/icons/joe-carstairs/.

- National Women’s Hall of Fame. “Helen Stephens.” Accessed March 24, 2019. https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/helen-stephens/.

- Oliver, Marie Watkins. “Helen Stephens.” The State Historical Society of Missouri. https://shsmo.org/historicmissourians/name/s/stephens/.

- Negro League Baseball Players Association. “Toni Stone.” 2012. http://www.nlbpa.com/the-athletes/stone-toni.

- Schwartz, Larry. “Althea Gibson broke barriers.” ESPN. https://www.espn.com/sportscentury/features/00014035.html.