The Effect of Choice in Repetitive Movement: An Evaluation of Dance Making and Mental Illness

The human species evolved to find patterns in our surroundings for survival, so it’s no mystery why repetition is a foundational narrative element in all forms of art. It can be used to add emphasis, establish the rules of a given landscape, or to manipulate the audience’s expectations. In my own dance making, and especially in my thesis work Mӧbius Storm (2021), I am interested in using repetitive movement to articulate both monotony and familiarity within a time-based performance.

While these ideas may seem at odds with each other, I feel that in life as well as in dance, monotony and familiarity are two sides of the same coin, (or perhaps more aptly, “both” sides of the same mӧbius strip.) In my experience, the difference between monotony and familiarity is choice. Repetition that is demanded can feel tedious, while repetition that is chosen can feel comforting and provide a sense of consistency. In Mӧbius Storm repetition is present throughout the piece but there is a dramatic tonal shift when the dancers choose repetition for themselves rather than allowing the repetition to control their actions.

As an individual living with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, this theme is an intimate exploration of my lived experience. I have a complicated relationship to repetition. I am often compelled to repeat actions or redo work as a symptom of my disorder, and though the actions themselves are benign, (re-washing hands, re-folding laundry, rearranging the objects in my vicinity,) they are done through compulsion rather than by choice. The lack of control is the issue more so than the result of the compulsion itself. While it is not my intention to mirror this experience in my dance-making, it is clear in retrospect that my work is heavily influenced by my experience with imposed repetition and OCD.

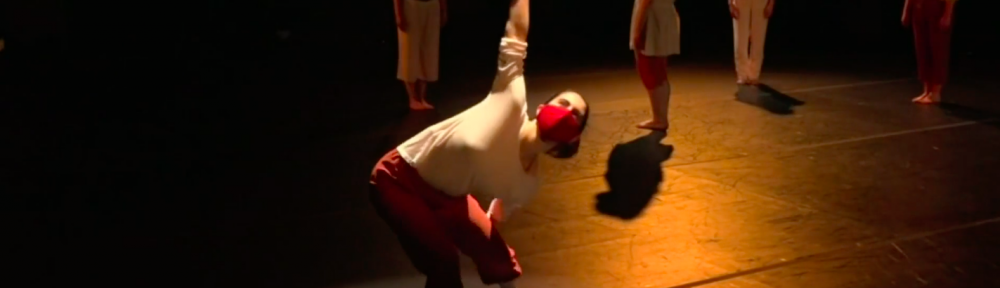

Recall the start of Mӧbius Storm, a clear example of repetition that emphasizes a lack of autonomy in the dancer. A quartet moves in unison through a sequence of evenly paced mechanical actions, reminiscent of something more robotic than human. The repetitive phrasing is intended to give the observer a clear sense that the dancer’s are confined by the environment and not free to move as they please. Even when the unison ends, the dancers begin an improvisational score using the same mechanical movements, reinforcing the limitations created by the set material.

Early in the rehearsal process, my advisor, Angie Hauser, encouraged me to find ways to complicate this section and “disrupt the metronome” of the dance. While this advice helped guide later sections of the work, I was resistant to altering the beginning of the piece. I wanted to acknowledge and share the tedium I had created. I was enjoying the creation of movement that lacked clear passion or interest on the part of the dancer. There’s a strong thematic tether between repetition and futility, and it became clear to me over time that I was using this section to represent my feelings of stagnancy brought on by the global pandemic as well as my ever present relationship to mental illness.

Additionally, I maintain that this effect cannot be created without repetition. While the type of movements being repeated informs the audience of a general tonal landscape, there is a narrative difference between moving in a stilted sequence, and moving in that same stilted sequence repeatedly. True repetition requires an absence of the unique. It emphasizes that the message is not just one of monotony and fatigue, but one of monotony and fatigue without end. This distinction was at the heart of my choreographic choices while making Mӧbius Storm, and continues to fascinate me as an artist.

In contrast, the final section of Mӧbius Storm is just as repetitive as the first but lacks the tediousness generated by the stylistic choices in the opening quartet. Now, all five dancers join in large jumps, spins, and kicks that create a more joyful and playful movement landscape. The base phrase for this section is less than a minute long, but it is repeated and remixed with other, similar set material to fill three minutes of stage time. So rather than strictly looping one section, dancers switch back and forth between the two phrases seemingly at random. This long form repetition, with increased variety, establishes a familiarity that counters the monotony created at the beginning of the dance.

Familiarity, containing the Latin root familia, meaning family, refers to something comforting and identifiable. The repetition provides that familiarity by giving the audience time to process the movements, so that they can recognize when those movements reappear. This part of the dance, as alluded to by the colorful lighting, can be compared to looking inside of a kaleidoscope. If the dance is made up of simple shapes and colors, then the image is continually shifting into new patterns without obscuring the individual components. This is not untrue of the repetition used in earlier parts of the piece, but is consciously used in a subtler way here, which removes any feelings of urgency or concern.

Most importantly, the main reason the repetition at the end of the piece has a different effect than the repetition at the beginning of the piece is the presence of choice. The rigorous “pilates hold” that defines the middle of the dance, just before the final section described above, culminates in each dancer choosing to relax into the ground once they’ve reached their limit. The dancers choose when their suffering ends, actively setting it aside in favor of comfort. This establishes a precedent for both the performers, and the audience, that the dancers retain the ability to choose for themselves what is best for their bodies. As the ending movement section begins, that awareness of choice isn’t lost, and the movement therefore seems more genuine and assenting.

These bookends to my thesis piece characterize the way repetition can be used for both negative and positive emotional effect depending on the presence of consent. The relationship between dancers and the material does not have to be friction-free or go unconfronted.

Perhaps it is entirely hypocritical of me, as the director and choreographer, to frame Mӧbius Storm as a representation of choice when the nature of the project requires the dancers to fulfill my artistic vision. But the interrogation of this concept stretches beyond this dance into the rest of my movement practice. It has been playing out in my personal life for years as I struggle to find peace living with OCD. I also think it broadly applies to society at large. What one person finds grueling and demeaning can be a source of joy for someone else, and again, it is the choice that separates these experiences.

Repetition can be an incredible tool for emphasis and clarity, and I encourage all creators to consider the potential narrative and thematic implications it can have in their work. How can it be used as more than an aesthetic choice? Why is a movement being repeated, and how might an observer interpret it? I continue to ask myself these questions as I reflect on my dance-making experience this semester, and hope to bring the discoveries I’ve made with me into my artistic future.

Möbius Ship

Möbius Ship

Tim Hawkinson (American, 1960-)

Currently on View in W404