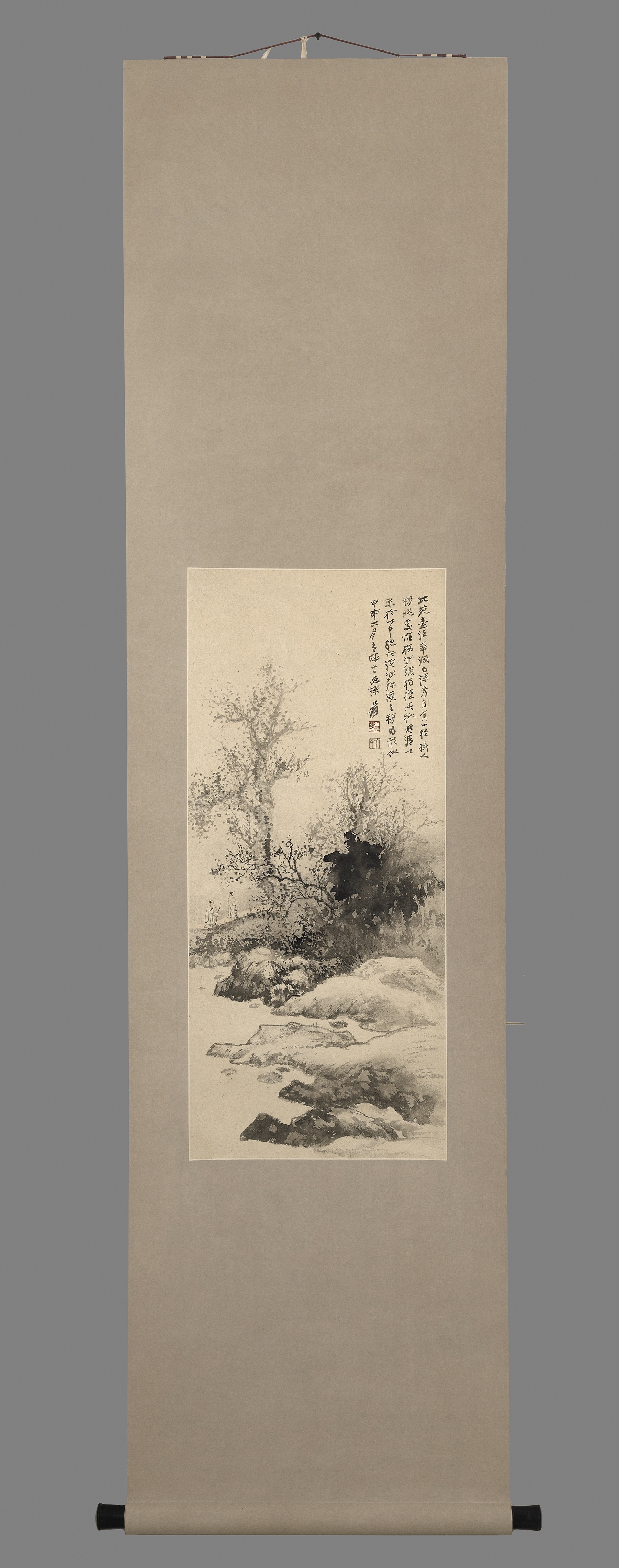

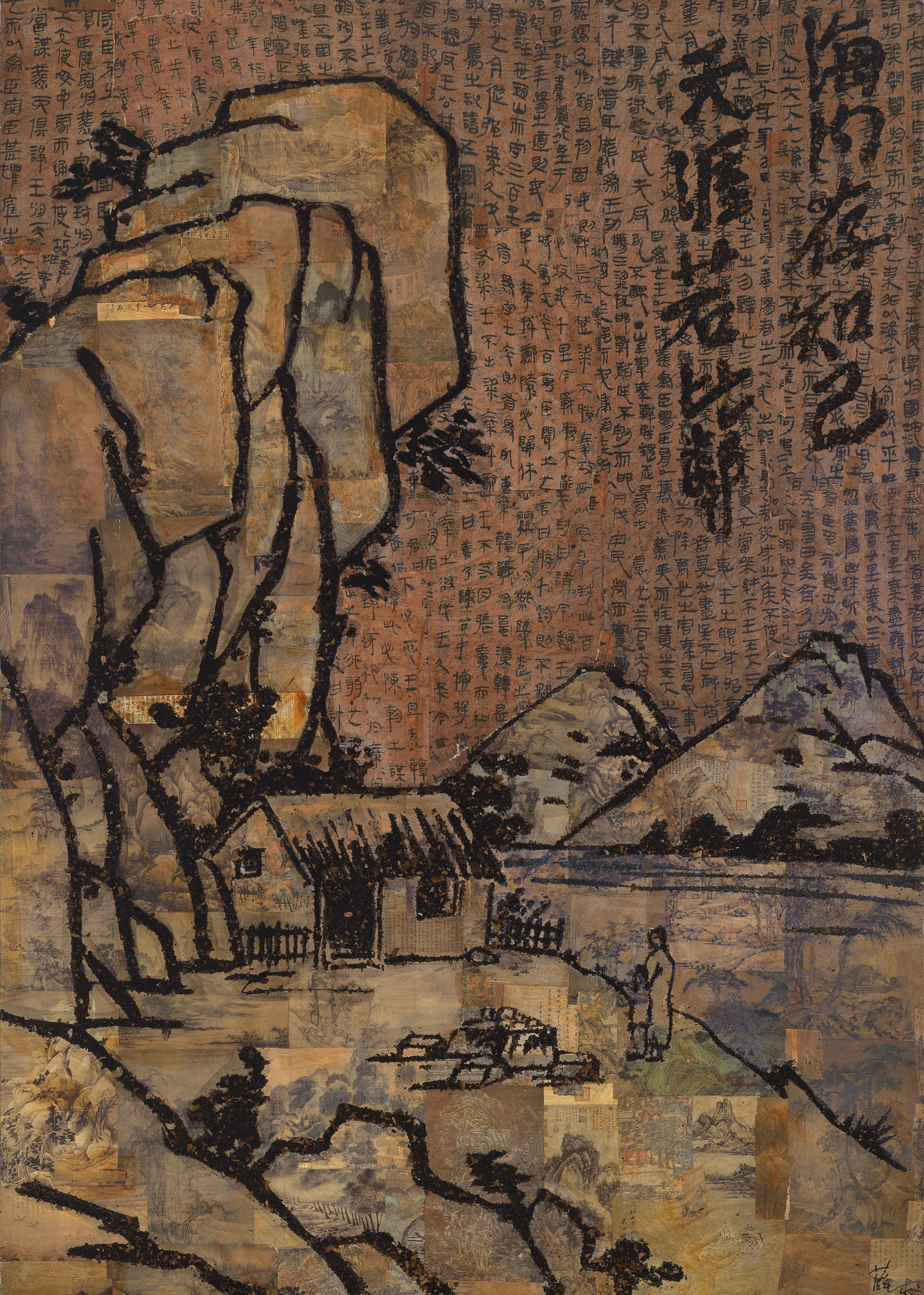

Unlike Western art, which focuses on originality, Chinese artists view the ability to capture and master another artist’s style as a talent. It is also a form of flattery and respect for the original artist. In Landscape, Zhang Daqian emulates the styles of two iconic landscape painters, Dong Yuan (934–962) and Mei Qing (1623–1697). The moist and elegant brushwork in the detailed illustrations of the budded branches and the rough crevices of the stones create a lively, yet serene spring landscape as two scholars enjoy their journey in seclusion.

The Tang-dynasty (618–907) poet, Wang Wei, known for his Fields and Gardens poetry, creates a personal and domestic scene of nature in Jin Bamboo Ridge. Devoted to Buddhism, Wang and Zhang often explored their journey toward enlightenment within their work. In the poem, Wang “enter[s] unseen on the Shang Mountain road,” where “even the woodsmen do not know,” implying a divide between the commoners and those who seek enlightenment and self-cultivation. Landscape, too, creates this contrast. The two scholars are on a journey, yet the destination is unknown—the viewers cannot see beyond the boundary of the work. The serene water, characterized by the white space, does not carry the reflection of surrounding lush vegetation. But like the water of the “deserted bend” at Jin Bamboo Ridge, it is so clear and empty that it “shines,” reflecting how emptiness is a state of mind.

Poem selection and label by Diana Chen ’17