A fictional boy shooting alien space bugs has nothing to do with life here on Earth, right? Wrong.

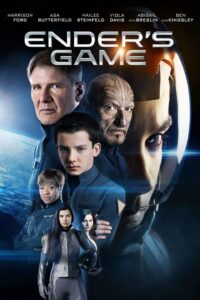

Ender’s Game is a science fiction novel that centers around six-year-old Andrew “Ender” Wiggin and spans seven years of his life. He is recruited to undergo an intense training program known as Battle School in order to become a soldier in his dystopian civilization’s space army. The army focuses on slaughtering an alien race referred to as bugs or “buggers”, who are viewed as an existential threat to humanity and their primary enemies. The book was written by Orson Scott Card in 1985, during the height of the Cold War. As an American during a time when the U.S. was embroiled in proxy conflicts all over the globe and fighting Communism on largely ideological grounds, Card grew up steeped in propaganda espousing the ontological evilness of any nation that dared to oppose free-market capitalism. However, Ender’s Game is a story about finding compassion for one’s perceived enemies, as Ender discovers that the bugs have a highly complex civilization with their own culture and social dynamics, and that they have desires outside of destroying humanity. In fact, both sides of the war feel that they are fighting for self-preservation and share a desire for peaceful coexistence, which allows Ender to empathize with the buggers and grapple with the morality of his actions as a soldier. Through this narrative, Card either consciously or unconsciously offers a critique of the America-First worldview, so devoid of nuance, that society has pressured him to adopt. If a reader were to comply with what Susan Sontag prescribes in her essay “Against Interpretation,” they would ignore this layer of meaning in Ender’s Game and focus on the story itself—Ender would be nothing more than a boy killing bugs in space, and the bugs would represent nothing more than bugs. Although the narrative is stylistically and structurally enjoyable on its own, the experience of reading Ender’s Game is heightened by its interpretation as an allegory for xenophobic war, challenging Sontag’s argument that interpretation is unequivocally detrimental to art.

Ender’s Game can be seen as mimesis, or an artistic representation of the real world, a concept whose value Sontag questions throughout “Against Interpretation.” The tale provides an allegory for a variety of historical and current conflicts as well as the Cold War. Ender is a young, brilliant child soldier forced into combat on behalf of an aggressive nation, which could represent the United States or any other major Western colonizer country. The bugs could symbolize the U.S.’s perceived enemies all over the world, but they could also be read as a placeholder for any Indigenous population striving to maintain their way of life in the face of settler colonialism. Therefore, the story and the moral lessons of Ender’s Game could be seamlessly applied to conflicts such as the ongoing war in Palestine, European settlers’ decimation of Indigenous North American populations, or any number of American military campaigns in Afghanistan or Iraq. These situations are all characterized by a lack of communication and understanding between Indigenous populations and colonizers. As Ender aptly assesses in the novel, “So the whole war is because we can’t talk to each other” (Card 160). Whether it is Ender’s fictional battle against the bugs, the conflict between capitalist and Communist forces worldwide during the Cold War, or practically any other global struggle for hegemony, most wars stem from xenophobia—prejudice against those perceived as different. Ender’s civilization certainly falls victim to this, blinded as to the morality of their actions by their hatred for their insect enemies. The key takeaway from Ender’s Game is that the most crucial tool in circumventing war is compassion. In the introduction, Card writes,

“I think that most of us, anyway, read these stories that we know are not “true” because we’re hungry for another kind of truth: the mythic truth about human nature in general, the particular truth about those life-communities that define our own identity, and the most specific truth of all: our own self-story. Fiction, because it is not about someone who lived in the real world, always has the possibility of being about oneself.”

This quote hints at his desire for readers to apply the message of Ender’s Game to reality and explains the human desire to project our own meaning onto fiction. Card thus validates the reader’s desire to connect with art on a personal level and read media as allegories for situations that are significant to them and relevant to their position in time and space. By connecting their own experiences to those of fictional characters, readers gain a sense of comfort, improve their ability to empathize, and are better able to internalize characters’ morality systems. In the case of a sympathetic character like Ender, this practice allows readers to recognize the importance of compassion as Ender eventually does.

Interpreting Ender’s Game as an allegory heightens our enjoyment of the story rather than hindering it as Sontag would suggest. Throughout the book, Ender is humanized over and over again. Born as the third child in a family with a two-child limit, he is a classic example of an outsider or underdog, a character with which readers are frequently inclined to sympathize. His homesickness and social challenges are almost universally relatable, even if the experience of training in an orbiting Battle School to fight alien bugs is not. And at the end of the story, even those bugs are humanized, revealing themselves to be highly intelligent through their attempts to communicate with Ender. They leave behind a baby Hive Queen, in the hope that he will have mercy on them and allow them to rebuild their civilization, and the intense vulnerability and humility illustrated by this act allows the reader to empathize with the bugs as well. By comparing oneself to these characters and projecting one’s life story onto them, the reader is able to derive meaning and personal connection. This level of engagement with the story is born of interpretation and heightens the pleasure of reading it. While Sontag would have the reader avoid such projection and focus on the stylistic excellence of the art itself, this may leave the reader with a shallower understanding of the narrative and characters as they are making a conscious effort not to relate to them on a personal level. In this scenario, the reader would also miss the richness of the universal message that Card lays out in Ender’s Game: that compassion is instrumental in subverting structural oppression and violence. That vital message would remain trapped between the lines, jailed in the fictional universe of the novel, never escaping into the world. Without consideration of the work’s historical context, the reader gains no new sense of perspective on the futility of the Cold War, reaping the benefits of only the narrative and not the metanarrative. It is completely possible to simultaneously appreciate Card’s exquisite dialogue, extensive characterization, and skillful worldbuilding and infer deeper meanings within the text, drawing clear connections to reality. If anything, this secondary exploration of the symbolism in Ender’s Game provides more utility to the reader than simply enjoying the story. This truth merits a reworking of Sontag’s statement, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” (pg. 10, section 10). In fact, a hermeneutics and an erotics of art can peacefully coexist—we need not sacrifice one for the other.

It is crucial that the reader acknowledge the mimesis in Ender’s Game, not just for their sake but for the world around them, as it allows them to think critically about reality and learn important moral lessons. Sontag dismisses the potential of art to reshape society thus, “Once upon a time (say, for Dante), it must have been a revolutionary and creative move to design works of art so that they might be experienced on several levels. Now it is not. It reinforces the principle of redundancy that is the principal affliction of modern life (9).” This is merely an unsubstantiated assertion, however, and does not diminish the fact that allegories such as Ender’s Game can still drive the moral improvement of society through the profound effects they have on their readers. First, readers realize the galling inhumanity of Ender’s world, born under an administration that remorselessly sends children to war to slaughter aliens indiscriminately. Then, they identify characters like Mazer Rackham who deceive Ender and his classmates into committing atrocities on a massive scale without informing them of the impact of their actions, and develop animosity toward those characters. Finally, they realize that these corrupt actors have real-world counterparts, and come away with both a new understanding of the problems plaguing their society and a framework for critiquing them and generating solutions. This example demonstrates that contemporary allegorical works are still profoundly valuable despite Sontag’s argument that the idea of including an allegory in art has been done so many times it is no longer worthwhile. Ender’s Game also exemplifies why mimesis is far from redundant or useless as Sontag universally characterizes it. This story can be a useful parable for teaching young people about the importance of compassion; because they are often introduced in childhood, fictional stories are an incredibly effective way to instill moral values and build historical knowledge. Through the application of stories like Ender’s Game to new scenarios, society can raise a generation of readers who are well-informed and self-aware, reducing the likelihood of future conflict both in their individual lives and in the world at large. Ender’s Game can be seen as an attempt to learn from humanity’s collective mistakes and avoid repeating such catastrophes as the Cold War, and it is thus morally reprehensible to ignore its allegorical nature.

Sontag would likely contest that Ender’s Game is enough on its own; that the reader does not need the added layers of meaning available through interpretation and that searching for these meanings is a futile endeavor that ultimately estranges us from the most important part of the art: its form. However, as previously established, the reader can still appreciate the compelling narrative and well-crafted prose Card provides, while also reaping the benefits of learning how to engage more critically with their world and question morally bankrupt power structures. Following the hidden narrative in this piece of art is additive to our experience, and why would the reader want to settle for less utility when they could have more? Sontag also conjectures that “It is always the case that interpretation of this type indicates a dissatisfaction (conscious or unconscious) with the work, a wish to replace it by something else. Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art” (6). She argues that interpreting art is inherently disrespectful to the artist for this reason. On the contrary, it is highly likely that Card intentionally wove the allegory into Ender’s Game, and ignoring it would actually be more disrespectful to his creative vision. A vast majority of science fiction works like Ender’s Game slip through the cracks of Sontag’s argument because, by nature, the genre lends itself to interpretation. It exists at the crossroads between satire and fantasy, often manifesting in portrayals of dystopian worlds that feel undeniably close to home. Sontag also makes the flawed assumption that all interpretation stems from dissatisfaction, when in reality it often comes from a love for a particular piece of art and a desire to engage with it on a deeper level. Especially in the case of science fiction works, which are often intended to serve as mimesis, interpretation doesn’t violate the art; it heightens the reader’s pleasure and understanding of the piece and makes it all the more meaningful to them.

Fictional stories like Ender’s Game represent opportunities to learn more about the world and critically examine it, opportunities that readers forgo if they stop trying to find hidden meaning in art. Viewing these works as parables allows them to endure and retain relevance far beyond their time. Ender’s Game was penned in the eighties, but it had a place in my 2010s childhood and instilled in me a hatred of war and a compassion for those I perceive as different. I doubt I would have gleaned nearly as much from the tale had I failed to grasp its real-life implications and allegorical nature. It is unrealistic to expect readers of fiction, and science fiction in particular, to completely mentally separate the world of the novel from reality. Attempting to do so would take the reader out of the moment and detract from the pleasure of the reading experience. Even if it were fully implemented, this practice would rob readers of the benefits of personal connection to characters, as well as any moral lessons they could have learned from Ender’s ultimate act of compassion. Any power that works could have in preventing xenophobia and war would be stripped away, and art would no longer be able to improve society beyond providing fleeting sensory pleasure. At the end of the day, if everyone abandons the search for subtextual meanings, humanity will be worse off, because the beauty of a book like Ender’s Game lies not only in its stylistic elegance but in its ability to shape a generation of young people to dream of a better world.

Works Cited

Card, Orson Scott, et al. Ender’s Game. Revised edition. New York, Tor, 1991.

Sontag, Susan. “Against Interpretation.” Against Interpretation, and Other Essays. Picador, 1966, pp 1-10.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.