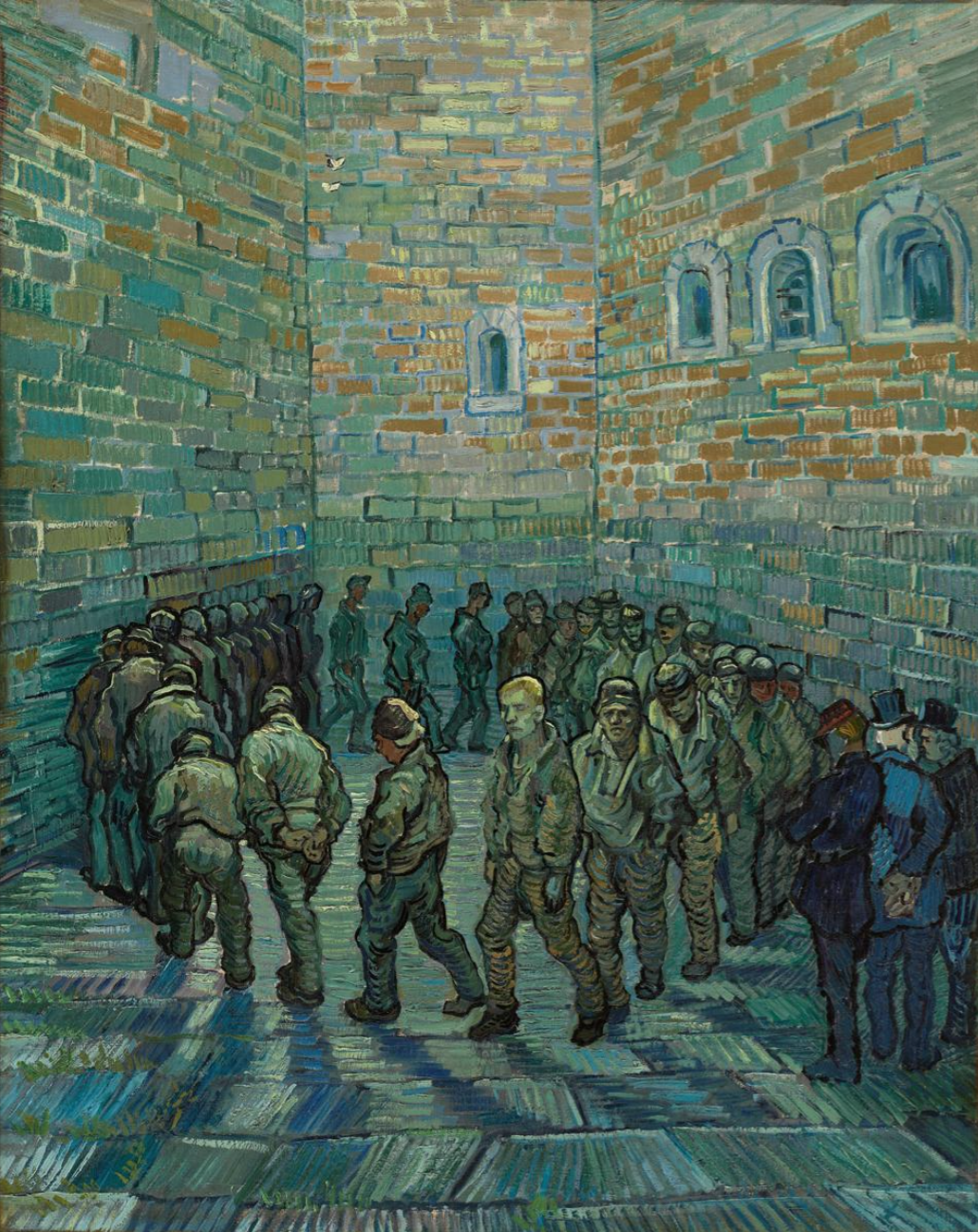

The work of Vincent van Gogh has recently gone through a reawakening in the way of the immersive van Gogh exhibit that used new technology to turn paintings into virtual reality. The paintings are projected onto the floors, walls, and even the ceiling of a warehouse, swirling softly as you walk through. What most people don’t know is that this isn’t the first time technology has been used to experience van Gogh’s work in a new way. In 1971, Stanley Kubrick created a movie based on Anthony Burgess’s book A Clockwork Orange. One of the scenes is a direct recreation of the Vincent van Gogh painting Prisoners Exercising, which van Gogh copied from Gustave Dorè’s engraving Newgate Prison Exercise Yard. Each artist, despite having very clear subject material, took liberties and added pieces of themselves. In his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin asserts that because the camera is a more precise artistic tool film lends itself to a different, more scientific, form of analysis than other art forms. This is true, but the analysis of film can then be applied to different forms of art and give us more insight into that art, as seen in the recreation of Prisoners Exercising in A Clockwork Orange.

Although we can see and analyze emotions through the movement shown in the painting, the technology of the film allows for the interruption of the main character’s movement and analysis of each individual moment. This analysis of a person in motion provides new knowledge that we can then apply to the still person in the painting. In the painting, there is one figure who stands out; he is the only prisoner not wearing a hat and his hair is bright red. It is possible that this character could represent van Gogh himself due to the similarities in appearance. Regardless of who he is supposed to represent, the main character stands out in another way: movement. His feet and face are angled out of the circle the prisoners are walking along. The same is true for Alex, the main character of A Clockwork Orange, but because you can see his movement in action, his emotions are more apparent. He walks with a relaxed swagger and often looks up towards the sky. Most of the other prisoners look defeated, but Alex doesn’t appear concerned with the monotony of his exercise as he casually converses with the man next to him. He simply looks up and away, as though looking for a way out. As Benjamin writes, “[e]ven if one has a general knowledge of the way people walk, one knows nothing of a person’s posture during the fractional second of a stride. The act of reaching for a lighter or a spoon is familiar routine, yet we hardly know what really goes on between hand and metal, not to mention how this fluctuates with our moods”(Benjamin, 16). When looking at the painting, one would likely be able to observe the movement of the main figure but because we can’t see it in motion, it is difficult to interpret what it means. Because the two characters move in very similar ways and Alex’s movement shows his desire to leave the prison, we can see that the main figure of the painting also dreams of escape. Knowing what the main character in the movie is feeling, we can look back at the painting and compare the two characters’ movements and emotions by using the film as an additional tool.

Cameras and other technology are much more precise than hand-created works that allow for human error. This accuracy does not necessarily mean that film is a better form of art, but it does allow for a different kind of analysis. Benjamin writes that “[a]s compared with painting, filmed behavior lends itself more readily to analysis because of its incomparably more precise statements of the situation” (Benjamin, 15). The camera very precisely recreates the point of view of the painting using an angle that provides the same distorted view of the prison yard as the painting does. However, because of this precision, some key features of the painting aren’t present. When juxtaposing these two visuals, some of the more unrealistic elements of the painting become abundantly clear. The walls of the painted prison extend up so far that the sky isn’t visible. There are two small white marks that appear almost like butterflies, completely incongruous with the dark prison setting. The windows are incredibly high off of the ground and unreachable by any of the prisoners. These details are very small and wouldn’t be noticeable unless the precision of the camera had pointed out the absence of them. The painting appears normal and realistic upon first glance, but when juxtaposed with the true realistic prison in the film, we can see the more artistic details and interpret what they mean. The butterflies could symbolize hope, while the unreachable windows and high walls could symbolize the impossibility of escape. The film can be analyzed scientifically because of its precision, but in this case the precision allows for another layer of analysis of the painting because it eliminates the unrealistic elements, making them more noticeable in the painting.

Most elements of film are also present in other visual art forms such as painting and photography, but the technological advancements of film also provide entirely new facets to interpret. The most obvious example of this is sound. In A Clockwork Orange, sound is where the film starts to take liberties with the content of the painting and Kubrick’s satirical intentions start to appear. In the background of the visual recreation of the painting and while the Minister of the Interior of England is doing an inspection of the prison, Kubrick plays Pomp and Circumstance. This song was originally used in 1901 during the coronation of King Edward VII, so it can be interpreted as a mocking of the authority of the Minister. As Benjamin states, “[f]or the entire spectrum of optical, and now also acoustical, perception the film has brought about a similar deepening of apperception” (Benjamin, 15). Sound provides us another way to connect film to a wider cultural context. Each connection provides a new path for interpretation, so the addition of sound in film allows for much deeper additional analysis of that film. We can then take the analysis of satire in A Clockwork Orange and look back at Prisoners Exercising to find similarities. What are the gentlemen in the corner of the painting supposed to represent? Could they symbolize the same satirized authority we see in the film? We would never have asked that question without the analysis of sound in A Clockwork Orange. The recreation in A Clockwork Orange gives us deeper insight into Prisoners Exercising because of the additional element of sound.

Each new form of the same content lets us look deeper into that content because of the addition of different elements. The film A Clockwork Orange recreates van Gogh’s Prisoners Exercising with additional elements of movement, precision, and sound. The new levels of analysis that come from these elements can be turned back around and applied to the painting to enhance our understanding. New creators are continuously using technology to reanimate old works. The immersive van Gogh exhibit uses the same additional elements of movement, precision, and sound to bring the paintings of van Gogh alive. Technology is constantly evolving, and each new advancement gives us a way to analyze and appreciate old works of art. We can breathe new life into the past using the technologies of the future.

Works Cited

A Clockwork Orange. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Warner Brothers, 1971.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Illuminations. Translated by Harry Zohn, edited by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, 1969, pp. 1-26.

van Gogh, Vincent. The Prison Courtyard. 1890, The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.