Scrapbooks are a complex archival resource, in that they are difficult to physically maintain and preserve, and that each scrapbook is inherently unique. Scrapbooking is a form of crafting and shaping a meaning out of the transitory material culture that surrounds the person creating it. It is at once a personal work, and expected to be shared with others as a source of temporary entertainment. There is a kind of literacy specific to looking for, clipping out, and arranging the found media in a way that serves as a means to self educate, and to create references for oneself and others.

Scrapbooking has long been associated with femininity and women’s organizations, a trend that goes back to the 19th century when women were encouraged to create “commonplace books”, the predecessor to the scrapbook. Despite the immense popularity of scrapbooking, it was considered to be trivial, and at worst, ‘gossipy’. However, women’s organizations, from literary clubs to reformist groups, used scrapbooks as a means to be even more rhetorically effective, “For women with no formal rhetorical

training, women’s organizations and the scrapbooks they compiled functioned as

alternative sites of education, a space for women to practice, learn, and reflect on

rhetorical practices specifically linked to the specific goals of individual groups” As Professor Mecklenburg-Faenger put it. Scrapbooks can be used for both personal, recording, and entertainment purposes, as well as serving as important educational tools to those who do not have the resources to educate themselves.

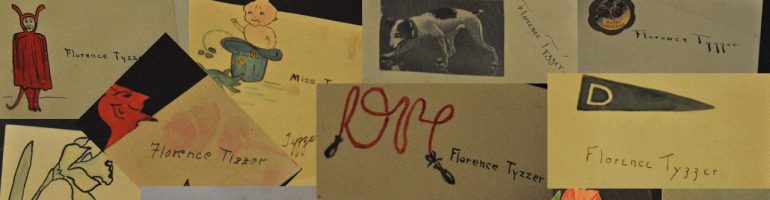

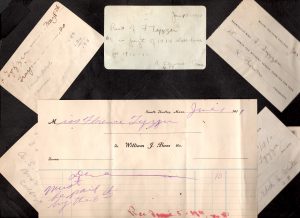

Along with being vital educational tools, scrapbooks have also always been a way for an individual to organize and compose their own experiences. Todd Gernes speaks about the trend of 19th century ‘friendship albums’ that women in college created, and Florence’s work fits in neatly; “Although the young student could not bring home the seminary’s library, mineral cabinet, or herbarium, she could certainly fill her album with poetry, art, and souvenirs of youthful friendship… The album became an outward sign of the compilers intellectual cultivation, aesthetic literacy, and verbal grace-“trophies” of culture”. Though I am unsure if Florence’s scrapbook can be counted as a trophy of worldly culture, it does certainly count as one of the culture of Mount Holyoke. Her scrapbook holds a remarkable collection of ephemera. It appears that Florence kept almost every paper that came her way, from the pamphlets for the many organ recitals that she attended, to the the photographs of her friends, the carefully saved exams, and the sports chants so carefully typed out, and even bills of the schools tuition, are all pasted into the pages. The careful recording of such every day and mundane items imply a sentimentality that is almost reverential, as well as paint a rich portrait of the life that she led at the school.

A page titled “Still Frolicking”, with a scrap of blue fabric, and multiple dance cards filled with the names of friends, all around a pamphlet about that years graduating class.

A series of photos of Florence and friends lounging among the trees at MHC

A collection of bills from the school

Florence Tyzzer did not create her scrapbook to help further a cause, but that does not make it any less valuable. The scrapbook began as a her own personal form of expression, possibly to entertain the people close to her, but it has become so much more in the 119 years since. Florence left a valuable source of information about what it meant to attend a women’s college at the start of the 20th century. The experiences and views that she embedded into her recycled postcard book are unique to her. Though that does create bias in any source, Florence’s physical interpretation of the time she spent at Mount Holyoke can still teach current and future staff and students more about what has changed, and what still needs to be worked on, so that Mount Holyoke, and other institutions, can continue to better themselves.