I

I

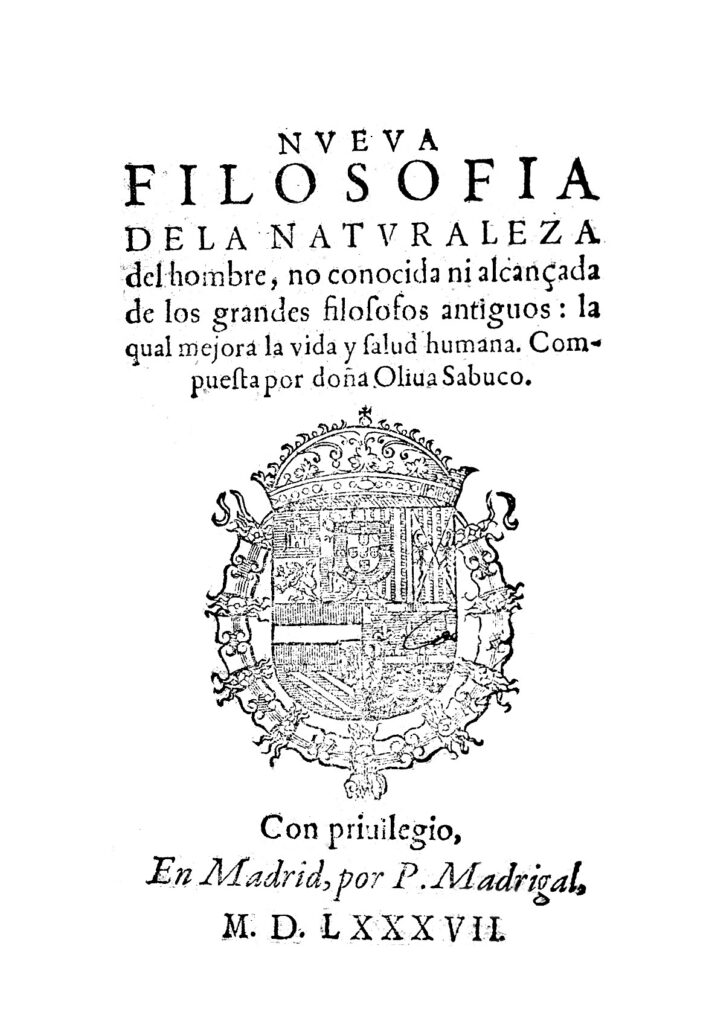

Doña Oliva Sabuco de Nantes y Barrera (1562–c. 1622/29) was the daughter of a chemist who believed in educating his daughter, but who later tried to claim her work as his own.2 She is known for writing New Philosophy on the Nature of Man, Neither Known to nor Attained by the Great Ancient Philosophers, Which Will Improve Human Life and Health (1587). The work questioned the ideas of the great classical philosophers and medical theorists, such as Aristotle and Galen, and posed questions that would later become central to the Enlightenment of the 18th century.3

While challenging centuries of medical understanding must have been daunting, Sabuco defended her assertion that she could improve upon the work of the great thinkers of the past. She said, “What you cannot deny me is medicine’s constant changes and the many times it has been modified,” indicating that she had studied developments in the history of medicine (Sabuco 179). She saw that our understanding of science is not static, and she chose to contribute her ideas to the wider discourse. Additionally, unlike many other women authors of her time, Sabuco’s dedication “offers no apology for the fact that it is published under a woman’s name.”5 She projected confidence in her theories and her scientific abilities at a time when women’s intellect was marginalized, both deliberately and by default.

Sabuco framed her treatises as Socratic dialogues, which would have been familiar to early modern readers. It guides the reader to the point that the author wants to make by addressing counter arguments that they might have to each individual point, building a case that, assuming the dialogue is well reasoned, is difficult to dispute.

Sabuco wrote extensively on the connections between the mind and the body, including how mental health and emotions can affect physical processes.6 Furthermore, she theorized about the transmission of diseases; she, in accordance with the dominant theory of the time, attributed the spread of some diseases to “bad odors or fumes that kill,” but she also presented an early theory of airborne transmission between humans (Sabuco 209). She suggested that “contagious diseases like the plague […] are carried by humans and enter through respiration and produce fatal decrements.”7

New Philosophy was reprinted several times during Sabuco’s lifetime, though up until recently the work was attributed to her father.8 Since the uncovering of her identity in 2006, her work has gained recognition as an important part of the history of women’s contributions to science.9

- Marta Macho Stadler, “La nueva filósofa, Oliva Sabuco (1562-1622),” Mujeres con ciencia, November 15, 2019, https://mujeresconciencia.com/2019/11/15/la-nueva-filosofa-oliva-sabuco-1562-1622/. ↩︎

- Sandra Plastina, “Oliva Sabuco de Nantes and Her Nueva Filosofia: A New Philosophy of Human Nature and the Interaction between Mind and Body, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, vol. 27, no. 4, (2019): pp. 738–52, 740, Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/09608788.2018.1549018.” ↩︎

- Stadler, “La nueva filósofa.” ↩︎

- See page for author, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. ↩︎

- Plastina, “Oliva Sabuco,” 741. ↩︎

- Leigh Ann Whaley, Women and the Practice of Medical Care in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1800 (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011): 69. ↩︎

- Doña Oliva Sabuco Barrera et al., “Proper Medicine Derived from Human Nature:,” in New Philosophy of Human Nature, Neither Known to nor Attained by the Great Ancient Philosophers, Which Will Improve Human Life and Health (University of Illinois Press, 2007), 177–252, p. 209, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1xcqnn.11. ↩︎

- Whaley, Practice of Medical Care, 69-70. ↩︎

- Whaley, Practice of Medical Care, 70. ↩︎