Though little is known about her personal life, Marie Meurdrac wrote La Chymie Charitable et Facile, en Faveur des Dames (The Charitable and Easy Chemistry, in Favor of Women). The book was published in 1666, and is often seen as the first chemistry textbook.

Women had limited access to scientific education and practice, so Marie Meurdrac taught herself and further developed all the chemical knowledge presented in La Chymie. The funding for her work and laboratory came from a noblewoman and Meurdrac herself taught private lessons to other women interested in chemistry.

Women’s education was of particular ideological interest to Meurdrac. She wrote in the preface of her book:

I dwelt irresolute in this combat almost two years. I objected to myself that teaching was not the profession of a woman; that she ought to remain in silence, to listen and to learn, without bearing witness that she knows: that it is above her to give a work to the public, and that such a reputation is not by any means advantageous …. I prided myself that I am not the first woman to have placed something under the press, that mind has no sex, and if the minds of women were cultivated like those of men, and if we employed as much time and money in their instruction they could become their equal.1

Her ideas about the intellectual equality of women to men were ahead of their time, and she obviously felt that it was important for her as a woman to do her part in proving it.

In her work, she wrote that the goal of chemistry was to extract from mixed bodies,

“the three Principals, which are Salt, Sulfur, and Mercury; which is done by two general operations, namely Solution and Congelation.”

Marie Meurdrac, La Chymie, 27

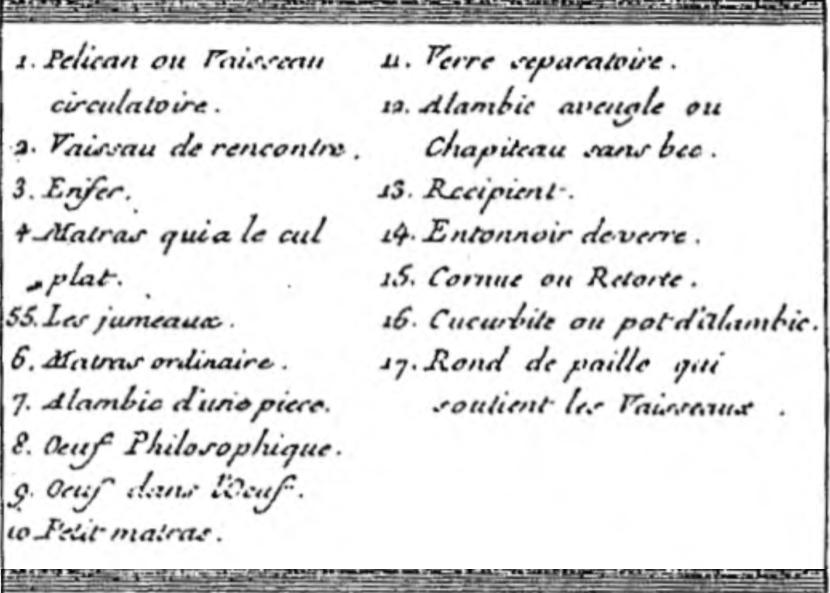

Meurdrac explained a variety of processes to achieve this goal, including distillation, rectification, filtration, desiccation, and fermentation, among many others.

Distillation was of particular interest, and Meurdrac discusses three different kinds of distillation: per ascensum, per medium cornutum, and per descensum. Per ascensum “raises the spirits in the form of smoke, or not finding a point of escape, they condense into water, and fall.”2 Per medium cornutum applies to spirits that “can’t raise themselves easily”3 while per descensum refers to heavy spirits that don’t rise at all.4

Marie Meurdrac also describes the medical benefits of a variety of plants. Of rosemary, she writes that it is, “a universal Antidote to all sorts of illnesses.”5 Marie Meurdrac also asserts the benefits of tansy: “It facilitates the childbirth of women, taking around 10 to 12 drops in two two spoonfuls of cinnamon.”6 She pays particular attention to the preparation of these herbs and the different forms these herbs can take, as an essence, tincture, or extract.

Meurdrac references religion several times throughout her work. She emphasizes the connection between religion and botanical simples, saying that they were first created to beautify the Earth, and then became medical necessities after the fall. She attributes the reported extreme longevity of biblical personnages to their consumption, and covers several instances within the Bible where holy men use simples to cure the sick.7 She goes so far as to claim that “Solomon could not have in justice been called wise had he not had a perfect understanding of the Simples.”8 Her belief in the capacity of the simples to extend the human lifespan goes beyond the biblical period; she says that “the deserts of Palestine have seen an infinite number of holy hermits pass the term that the Prophet gives to the life of man and live a hundred and six score years, without taking any food but the Simples.”9 The religious bent of some of her work separates her from the more Deist sensibilities of the Enlightenment.

Marie Meurdrac was a pioneer in the field of chemistry a champion of women’s education. Although she has been largely forgotten by history, she was obviously a brilliant and impassioned woman who managed to devote herself to science, despite the contemporary societal expectations.

- “Preface” in Marie Meurdrac, La Chymie Charitable & Facile. En Faveur des Dames (Paris, author’s edition, 1666). Cited in Lucia Tosi, “Marie Meurdrac: Paracelsian Chemist and Feminist,” Ambix 48, no. 2 (July 2001): 71-72. ↩︎

- Marie Meurdrac, La Chymie Charitable et Facile en Faveur des Dames, (originally printed 1966), ed. Jean Jacques (Paris, 1999), 31. My translation. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 31. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 32. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 65. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 69. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 55-56. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 56. ↩︎

- Meurdrac, La Chymie, 56. ↩︎