Who was Jean de Léry?

Jean de Léry was a French explorer and writer born in the 1530s in Margelle (Bourgogne), France. He was a Protestant during the Wars of Religion, and he moved to Geneva in 1552. Geneva was a haven for francophone Protestantism because it was the home of Jean Calvin, the leader of the Protestant Reformation. In 1557, he arrived at a French colony for persecuted Protestants in Brazil with a group of Calvinist ministers.1

The founder of the colony, Nicolas Durand, le chevalier de Villegagnon, promised religious freedom to those who arrived. However, over time, Villegagnon reconverted to Catholicism and began persecuting the Protestants. After eight months, the Protestants, including Jean de Léry, left the colony and relocated to a location in close proximity to the Tupinambá people (Tupi) of the region.2

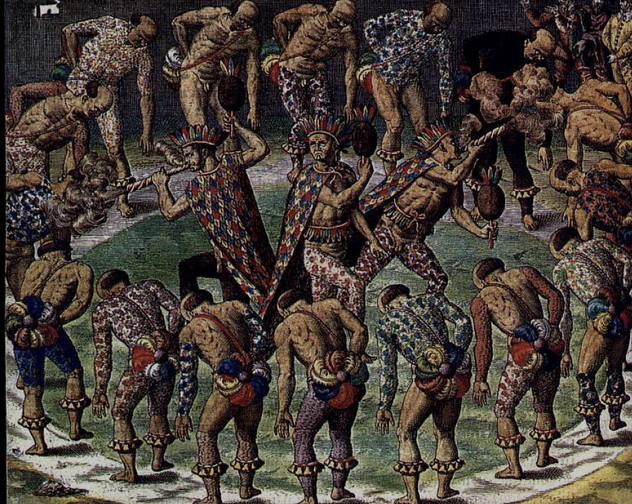

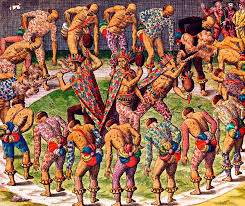

Jean de Léry resided with the Tupinambá for a year. During this time, he took detailed notes about the culture and customs of this Indigenous people. In 1578, he published L’Histoire d’un voyage fait dans la terre du Brésil, which was the first French ethnographic work published.3 His book describes the rituals and ceremonies of the Tupinambá, as well as translations of songs, food, clothing, and the flora and fauna he observed during his travels. Importantly, he reflected on contemporary religious attitudes in Europe and drew connections between the cannibalism of the Tupinambá and the cruel behavior of Europeans during these wars.4

Who Were/Are the Tupinambá

The Tupinambá are South American Indigenous peoples who, from the 16th-17th century inhabited the Eastern coast of Brazil from Ceará to Porto Alegre. They are one group of Native people speaking the Tupian language. During this time, the Tupinambá resided in large patrilineal villages of about 1000 people. They are thought to have had a sizable population across twenty-seven villages from the 16th to 17th centuries.6 They were the largest Indigenous coastal group of the period.7

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Tupinambá relied on agricultural cultivation supplemented with hunting and fishing. They grew maize and manioc (cassava), as well as beans, pineapple, sweet potato, peanuts, and pepper to sustain their community. After the arrival of European colonizers, they began additionally growing bananas, sugar cane, and sorghum that were introduced.8

When the Portuguese began their conquest of Brazil through colonization, the Tupinambá were forced to constantly migrate in order to escape enslavement. In attempts to take back their land, their villages waged wars in response to various French, Dutch, and Portuguese incursions. These battles decimated the Tupi population through violence and disease. As a result, their population was nearly eradicated.9

Today, there are only two small regions in Brazil where the Tupinambá continue to reside.10

In 2004, the Tupi began regaining control of some areas of their territory after around five centuries of massacres and forced removals. Their regained territory is covered by the rich Atlantic forest and is known to the Tupinambá as the home of the “enchanted ones.” According to their traditions, the forest is home to the gods and is “the source of all life.”11 Today, the Tupinambá “remain committed” to fighting the Brazilian state to regain their right to their land.12

For more information on the Tupinambá, you can watch this documentary: Tupinambá: The Return of the Land (2015). The short documentary tells the story of centuries of struggle by the Tupinambá to remain on their land using archival footage and interviews with those who currently live in the Tupinambá de Olivença Indigenous Territory. In honor of the Encantados (Ancestral Sipirits), the Tupinambá have resisted violent incursion from colonizers and the Brazilian government in order to protect their sacred land. Importantly, through their struggle for land, the Tupinambá show the strength of their relationship with their environment, saying “you do not commercialize land, land is for living, it’s for working, planting, and harvesting” not for commercialization.13

- Brock, Theresa. 2024. “Jean de Léry pt 1.” PowerPoint presentation, Smith College, Northampton, MA, February 21, 2024. ↩︎

- “University of Virginia Library Online Exhibits | the Renaissance in Print: Sixteenth-Century Books in the Douglas Gordon Collection.” n.d. University of Virginia Library. University of Virginia. https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/renaissance-in-print/travelnarratives/lery. ↩︎

- Brock, Theresa. 2024. “Jean de Léry pt 1.” PowerPoint presentation, Smith College, Northampton, MA, February 21, 2024. ↩︎

- Léry, Jean de. History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America. Latin American Literature and Culture: 6. University of California Press, 1990. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=cat09206a&AN=scf.oai.edge.fivecolleges.folio.ebsco.com.fs00001006.0150522a.5d7d.592c.b834.317e3a40f18c&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↩︎

- Bibliothèque nationale de France. n.d. “Gallica – France Amérique – Attempts at Colonization in the 16th Century.” Gallica.bnf.fr. Digital Library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://gallica.bnf.fr/dossiers/html/dossiers/FranceAmerique/en/D2/T2-2-1.htm. ↩︎

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012. “Tupinambá | People | Britannica.” Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. September 26, 2012. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tupinamba. ↩︎

- Araújo, Marcos, and Tábita Hünemeier. 2023. “A Multidisciplinary Overview on the Tupi‐Speaking People Expansion.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, November. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24876. ↩︎

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012. “Tupinambá | People | Britannica.” Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. September 26, 2012. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tupinamba. ↩︎

- Beierle, John. 2003. “Culture Summary: Tupinamba.” New Haven, Conn.: HRAF. https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/document?id=so09-000. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Overbeek, Winnie. 2014. “Brazil: The Struggle of the Tupinamba Indigenous People to Protect Their Territory and the Conservation of Forests | World Rainforest Movement.” wrm.org. World Rainforest Movement. October 31, 2014. https://www.wrm.org.uy/bulletin-articles/brazil-the-struggle-of-the-tupinamba-indigenous-people-to-protect-their-territory-and-the-conservation-of. ↩︎

- Intercontinental Cry. 2015. “Tupinambá: The Return of the Land | Intercontinental Cry.” Intercontinentalcry.org. 2015. https://intercontinentalcry.org/tupinamba-the-return-of-the-land/. ↩︎