Comparing French Colonial Relationships to Flora in Brazil and New England: Brazilwood and Sassafras

I. Sassafras

The Abenaki are a group of Native people indigenous to Quebec and New England,1 who, like the Tupinambá, experienced the extractive effects of colonization by the French. Dr. Marge Bruchac, an Abenaki woman specializing in the history of her people, visited Smith College to give a lecture about Abenaki “Indian Doctresses.”2 Indian Doctress is the term used by Dr. Bruchac to describe the Abenaki women who served as doctors during colonization. Her lecture focused specifically on their relationship to the land through herbal medicine.

Dr. Bruchac highlighted the fact that colonizers from Europe would learn of and use the cures from the Indian Doctresses. Importantly, she emphasized that the colonizers would exploit Indigenous remedies.3 Specifically, she spoke of the consequences of French colonization on one specific plant: Sassafras. Until the latter half of the twentieth century, Sassafras was used as a cure for syphilis.4 Indian Doctresses introduced British and French colonizers in the region to the plant’s root as a natural remedy for the disease.5 However, when the invaders learned of the cure, they began stripping forests of the plant and shipping it to Europe to aid during syphilis outbreaks.6 As a result of this exploitation, the plant was on the brink of extinction in its native habitat. Dr. Bruchac explained that the Abenaki “knew ways of harvesting [sassafras] without hurting the plant community,” something the colonizers did not understand.7 Today, the Abenaki continue their work to restore the tree in this region.8 This is one of many examples that illustrate the devastating effects of extractive colonization on Indigenous ecology.

II. Brazilwood

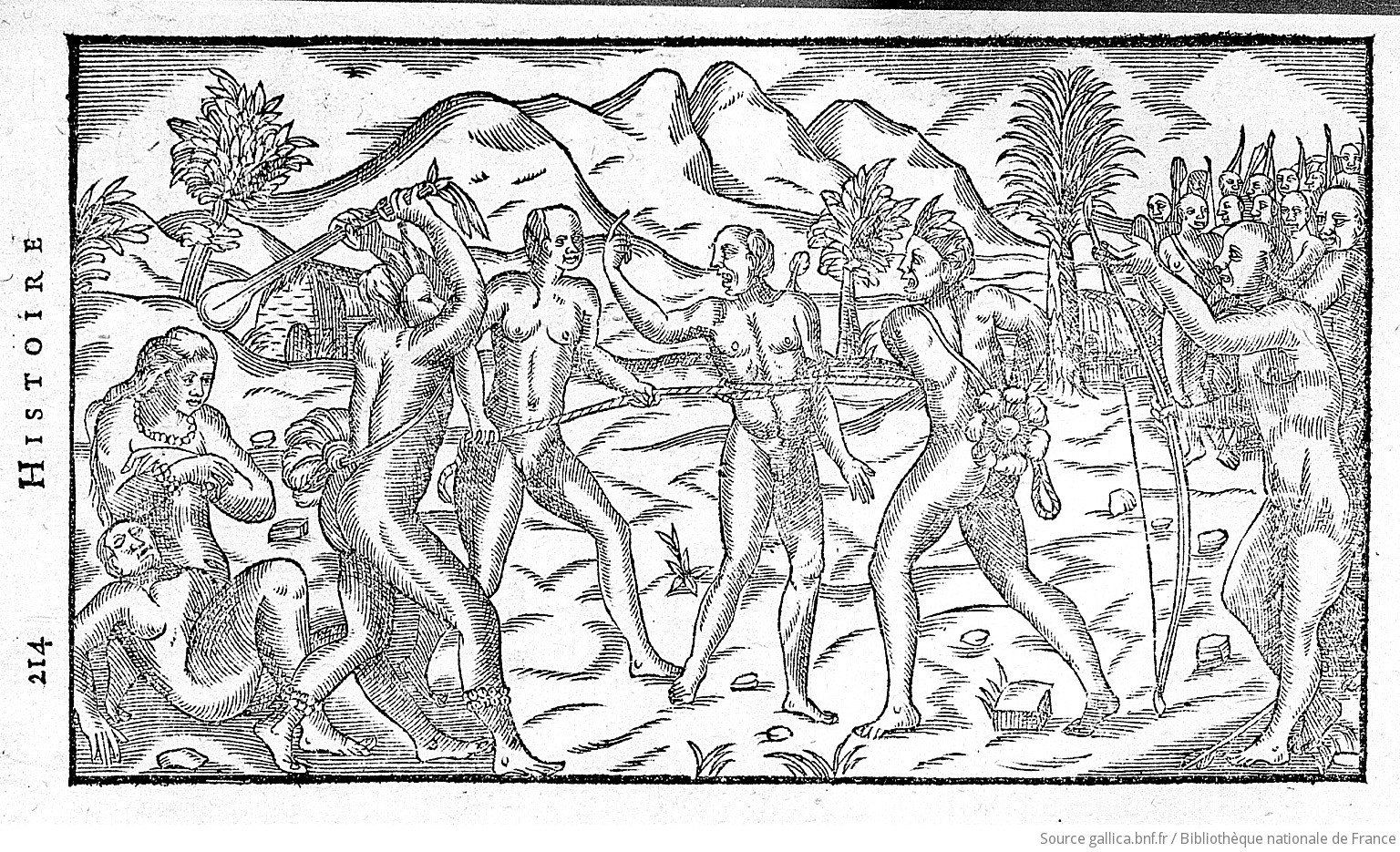

Returning to Jean de Léry’s History of a Voyage […], we can observe an early example of decolonial critique through a conversation between de Léry and a Tupi tribesperson on the topic of European extraction of brazilwood, a coveted resource used to manufacture a rare red dye. After De Léry explains the justifications for brazilwood extraction,9 the Tupi man replies, “[…] I see now that you [French] are great fools; must you labor so hard to cross the sea […] just to amass riches for your children or for those who will survive you? Will not the earth that nourishes you suffice to nourish them?”10

We found Jean de Léry’s response quite progressive for his time. He demonstrates an openness to critique of his culture of origin and is well-aware of the non-cogency of the colonial project; “This nation, which we consider so barbarous, charitably mocks those who cross the sea at the risk of their lives to go seek brazilwood in order to get rich.” 11 De Léry represents a unique exception among his European contemporaries in the realm of colonial writing and discourse; as a twice-persecuted Protestant, having fled France to settle in the Brazilian colony only to flee once again after the conversion of their leader to Catholicism,12 de Léry demonstrates an openness towards Tupi cultural practice and openly critiques European modes of thought. He explains why he chose to include this exchange, saying that, “To our great shame, and to justify our savages in the little care they have for the things of this world, I had to make this digression in their favor.”13

Finally, it is important to note that colonial extraction of Brazilwood relied on Indigenous labor. De Léry observes that, “[…] if the foreigners who voyage [to Brazil] were not helped by the savages, they could not load even a medium-sized ship in a year.”14 Therefore, colonial commerce was dependent not only access to land– which often resulted in the displacement of Indigenous populations– but was also dependent on the cooperation of local peoples. We can conclude that a colonial relationship with flora is not separate from colonial relationship to native peoples; the two inter-are.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Abenaki.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Abenaki. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret. “Walk with the Indian Doctress: Restorative Approaches to Interpreting Native American Medicine.” PowerPoint presentation, Smith College, Northampton, MA, April 15, 2024. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret M. “Abenaki Connections to 1704: The Sadoques Family and Deerfield, 2004.” Captive Histories: Captivity Narratives, French Relations and Native Stories of the 1704 Deerfield Raid (2006): 262-78. ↩︎

- Manning, Charles, and Merrill Moore. “Sassafras and Syphilis.” The New England Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1936): 473–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/360282. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret. “Walk with the Indian Doctress: Restorative Approaches to Interpreting Native American Medicine.” PowerPoint presentation, Smith College, Northampton, MA, April 15, 2024. ↩︎

- Willard, Fred L., Victor G. Aeby, and Tracy Carpenter-Aeby. “Sassafras in the New World and the Syphilis Exchange.” Journal of Instructional Psychology 41, no. 1–4 (March 2014): 3–9. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=asn&AN=102742799&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret. “Walk with the Indian Doctress: Restorative Approaches to Interpreting Native American Medicine.” PowerPoint presentation, Smith College, Northampton, MA, April 15, 2024. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Jean de Léry and Janet Whatley, History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America (Berkeley, Calif: Univ. of California Press, 2006). ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Michèle Tillard, “Jean de Léry, Histoire d’un Voyage En Terre de Brésil (1578-1611): Philo-Lettres,” Philo, accessed May 9, 2024, https://philo-lettres.fr/litterature-francaise/litterature-xvieme-siecle/lery/. ↩︎

- Jean de Léry and Janet Whatley, History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America (Berkeley, Calif: Univ. of California Press, 2006). ↩︎

- ibid.. ↩︎