Sassafras albidum

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) is a plant with a tumultuous history. Native to much of the Eastern United States, many parts of this tree have been prized by many cultures for centuries. Indigenous tribes use the leaves of this plant to thicken soups and stews and the Louisiana Creole dish known as fievé gumbo uses powdered sassafras.1 After European explorers first reached what is now Massachusetts in the 17th century, sassafras became one of the earliest exports from North America to Europe.2 English colonizer Martin Pring wrote that sassafras was “a plant of sovereign virtue for the French Poxe, and…good against the Plague and other maladies.”3 Pring most likely recognized the medicinal value of sassafras after reading Joyfull Newes Out of the Newe Founde World by the Spanish doctor Monardes, published in English in 1577. Monardes purportedly recorded his observations of native medicine in the Spanish colonies. The “French Poxe” Pring refers to is an antiquated term for syphilis. Though modern research reveals that syphilis likely originated in Southwest Asia, it was widely held at the time that the disease had been brought over from the Americas.4 Thus, European physicians of the era concluded that the cure must also be found across the Atlantic.

European colonizers began massive harvests of sassafras, felling countless trees to harvest their medicinal roots (Bruchac).5 While these colonial harvests killed every tree they touched, native communities had methods of extracting the root without killing the tree. According to Monardes, the Indigenous Americans took only a piece of the roots and “thei cut it into verie thinne, and little peeces, and cast them into water” which they drank when needed.6

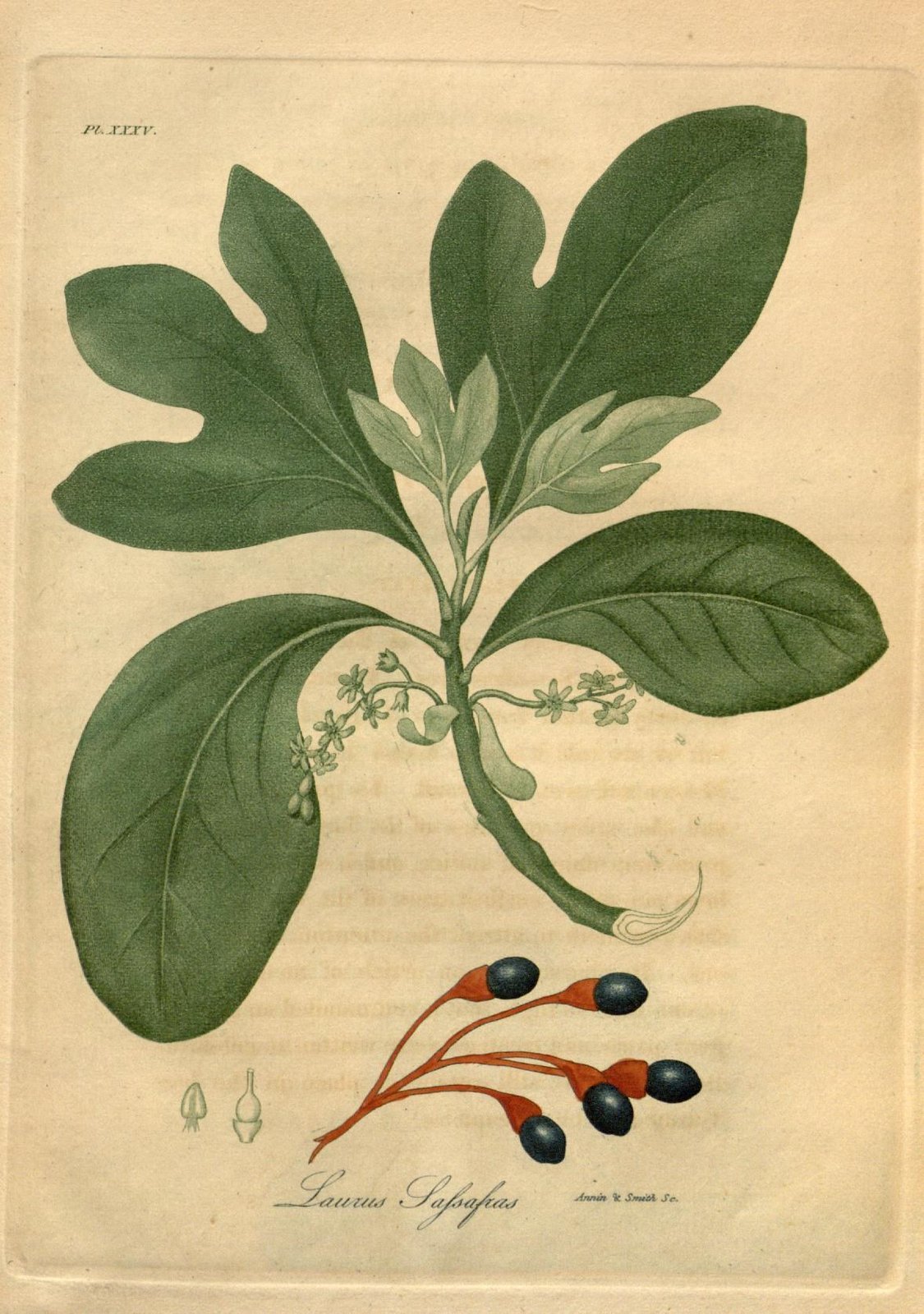

Since the sassafras craze of the 17th century, sassafras has been widely used in medicine and commercial products. 19th-century physician Stephen West Williams of Deerfield, Massachusetts, described L. Sassafras in his herbarium, which was profoundly influenced by his association with Abenaki doctor Louis Watso.7 Williams wrote of sassafras, “The root…is highly aromatic and stimulant. The pith is very demulcent, and…is useful in dysentery, catarrh, and ophthalmia.”8 Sassafras root was also used in the original Hires Root Beer recipe.9 Since then, safrole, an oil found in plants such as sassafras, nutmeg, and sasparilla, has been labeled carcinogenic due to a study that exposed rats to high levels of safrole.10 Studies of such cancer-causing effects in humans are still inconclusive.

Sassafras trees are easy to spot in the wild. They are dioecious, meaning that there are male and female sassafras trees.11 Female trees bloom between March and April, producing small yellow flowers. They then produce dark blue berries attached to red pedicels. Sassafras leaves have three main shapes: ovular, three-lobed, and classic mitten. They are particularly easy to spot in the fall when the leaves turn a dusky red.

- Shade, Pam. “Sassafras: Native Gem of North America.” Cornell Botanic Gardens, Cornell University, 10 October 2022, https://cornellbotanicgardens.org/sassafras-native-gem-of-north-america/. Accessed 5 May 2024. ↩︎

- Manning, Charles, and Merrill Moore. “Sassafras and Syphilis.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 9, no. 3, 1936, pp. 473–75. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/360282. Accessed 5 May 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, Benea V, Georgescu SR. “Brief history of syphilis.” J Med Life, vol. 7, no. 1, 15 March 2014, pp. 4-10. Epub 2014 Mar 25. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret. “In Search of the Indian Doctress.” Native Plant Knowledge with Dr. Margaret Bruchac, 15 April 2024, Smith College, Northampton, MA. Lecture. ↩︎

- Monardes, Nicolás. Joyfull newes out of the new found world: wherein are declared the rare and singular vertues of divers and sundrie herbs, trees, oyles, plants & stones, with their applications as well to the use of phisicke, as chirurgery … Also the portrature of the sayde herbes, very aptly described. W. Norton, 1580. ↩︎

- Bruchac, Margaret. “Abenaki Connections to 1704: The Sadoques Family and Deerfield, 2004.” Bruchac, Margaret. “Abenaki Connections to 1704: The Sadoques Family and Deerfield, 2004.” In Captive Histories: Captivity Narratives,

French Relations and Native Stories of the 1704 Deerfield Raid. Evan Haefeli and Kevin Sweeney, eds. pp. 262-278. Amherst, MA:

University of Massachusetts Press. ↩︎ - Williams, Stephen W. Report on the Indigenous Medical Botany of Massachusetts, 1849. ↩︎

- (Shade 2022) ↩︎

- McVean, Ada. “The Root in Root Beer is Sassafras.” Office for Science and Society, McGill University, 22 February 2018, https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/root-root-beer-sassafras. Accessed 5 May 2024. ↩︎

- (Shade 2022) ↩︎