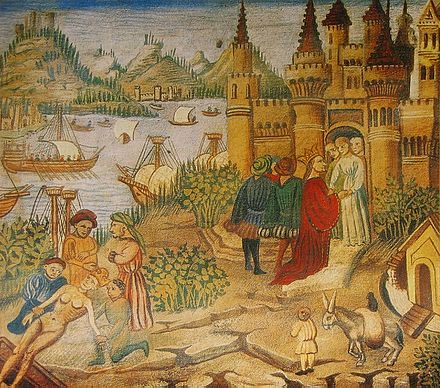

The institutionalization of medical and scientific knowledge in universities effectively shut women out from the formal healthcare profession. This exclusion caused women to practice on the periphery as midwives, nurses, unofficial village healers, and family caretakers.1 The marginalization of women through educational inequalities elevated men to be more respected in the medical field due to their academic experience.2

Many of the women who practiced medicine and science from the 16th to the 18th centuries taught themselves and relied on practical knowledge, an important distinction from the trope of male doctors burying their nose in a textbook. Marie Meurdrac, a female self-taught chemist, wrote, “action teaches us much more than contemplation.”3 On this page, we explore the less well-understood contributions of female medical practitioners and scientists during the early-modern period in France.