La foule dans Bel-Ami

Première partie, ch. I

Quand Georges Duroy parvint au boulevard, il s’arrêta encore, indécis sur ce qu’il allait faire. […] Il tourna vers la Madeleine est suivit le flot de foule qui coulait accablé par la chaleur. […] La foule glissait autour de lui, exténuée et lente, et il pensait toujours: «Tas de brutes ; tous ces imbéciles-là ont des sous dans leur gilet.» Il bousculait les gens de l’épaule, et sifflotait des airs joyeux.

pp. 46-48

Seconde partie, ch. X

Du Roy l’écoutait [l’évêque], ivre d’orgueil. Un prélat de l’Église romaine lui parlait ainsi, à lui. Et il sentait derrière son dos, une foule, une foule illustre venue pour lui. Il lui semblait qu’une force le poussait, le soulevait. Il devenait un des maîtres de la terre […] Lorsqu’il parvint sur le seuil [de la Madeleine], il aperçut la foule amassée, une foule noire, bruissante, venue là pour lui, pour lui Georges Du Roy. Le peuple de Paris le contemplait et l’enviait.

p. 369, p. 371

Images

Artistes et sociologues

Vallotton, Taine, Tarde, Le Bon

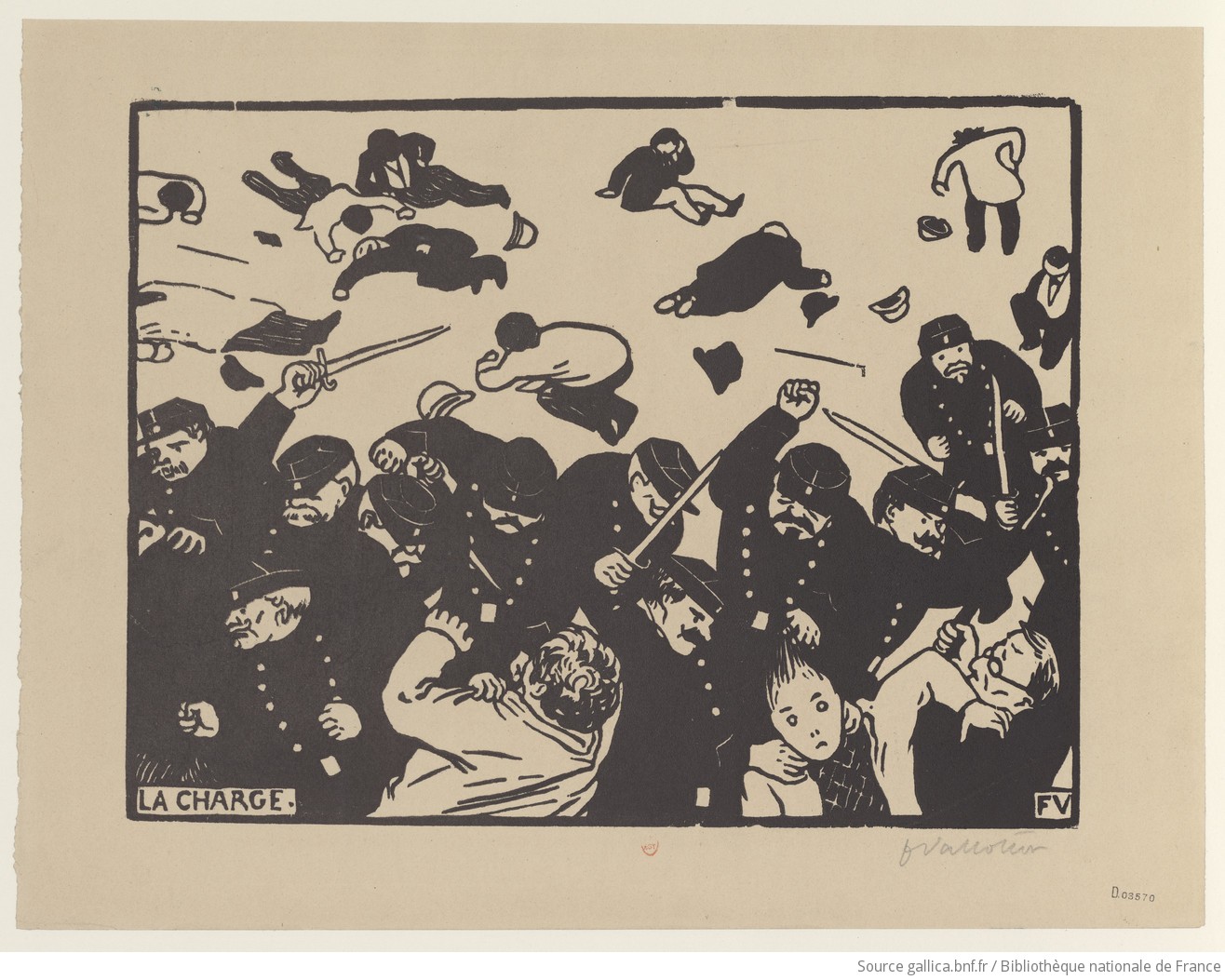

Vallotton’s pictorial approach to the crowd was forged amid an explosion of historical, sociological, and philosophical interest in the subject. From 1876 to 1894 Hippolyte Taine published a six-volume account of French history since the 1789 Revolution. Les Origines de la France contemporaine is laced with hostility toward—and sensational descriptions of—the unruly crowds that propelled this period of radical change. Taine describes the crowd as “un animal primitif,” a thoughtless force of destructive anarchy (vol. 3 [1878], 70).1 Drawing on Taine, sociologists Gabriel Tarde and Gustave Le Bon (among others) made crowd psychology a new branch of scientific inquiry. Tarde, an original philosophical thinker, saw the crowd as an aggregate of imitative individuals, each of whom bears the potential for sympathy and innovation as well as conformity and irrational violence. Le Bon, who popularized Tarde’s ideas, doubled down on the negative view. His notorious best-seller, La Psychologie des foules (1895), describes the crowd as dumb and dangerous yet manipulable by a charismatic leader, especially if that leader wields power in the form of images. Rational individuals transform through collective contagion, mutually intoxicated by “l’impulsivité, l’irritabilité, l’incapacité de raisonner, l’absence de jugement et d’esprit critique, l’exagération des sentiments” (24).

Vallotton’s vision of the crowd could be called Tardian in its contradictions, but with a leftist bent. His ambivalent figures frequently look out as if to hook our attention, soliciting the viewer’s identification with their dilemma. In La Charge we are addressed by the passive policeman and the young dissident, who stares straight ahead with one policeman grabbing his neck and another about to strike his head with a fist. Whose side are you on, Vallotton seems to ask, and what will you do from where you stand? Other prints by the artist from the early to mid 1890s—depicting suicide, capital punishment, political protest, and public brawls—similarly place the viewer in uncomfortable positions of political fence-sitting and ethical doubt.2

Bridget Alsdorf, “Vallotton, Fénéon, and the Legacy of the Commune in Fin-de-siècle France,” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 49, nos. 3 & 4, Spring–Summer 2021, pp. 272-273

L’Affaire Dreyfus et les théories de Gabriel Tarde

Les répercussions de l’Affaire sur l’opinion publique peuvent historiquement s’expliquer par plusieurs phénomènes. Tout d’abord celui de la presse sur laquelle s’appuie l’opinion publique, jour après jour elle rend compte du développement de l’Affaire et diffuse ses propres mythes. Tout en elle joue sur le registre passionnel. Mais elle est aussi l’intermédiaire par lequel l’événement lui-même passe. Ensuite, les principales figures de l’Affaire sont des écrivains, des « intellectuels » : la nouvelle figure de l’intellectuel engagé crée l’événement, elle engendre le combat par la polémique, elle s’oppose aux institutions et au pouvoir au moyen de l’écriture. Une nouvelle société émerge. L’Affaire représente alors une évolution dans l’histoire de la démocratie : elle déplace l’instance de décision de l’ombre des ministères à la place publique ; elle consacre le triomphe des puissances d’opinion (assemblées, presse, instances locales) sur les puissances traditionnelles (notables, armée, justice).

Louise Salmon, « Gabriel Tarde et l’Affaire Dreyfus », Champ pénal/Penal field [En ligne], Vol. II | 2005

- The classic Jacobin critique of Taine’s account of revolutionary crowds is Georges Lefebvre, “Foules révolutionnaires,” Annales historiques de la Révolution fr ançaise, no. 61, Jan.- Feb. 1934, pp. 1-26 ↩︎

- Cf. Le Suicide, 1894, woodcut; L’Exécution, 1894, woodcut; La Manifestation, 1893, woodcut; Au Violon, 1893, zincograph; La Rixe, 1892, woodcut. ↩︎