By G. Gans

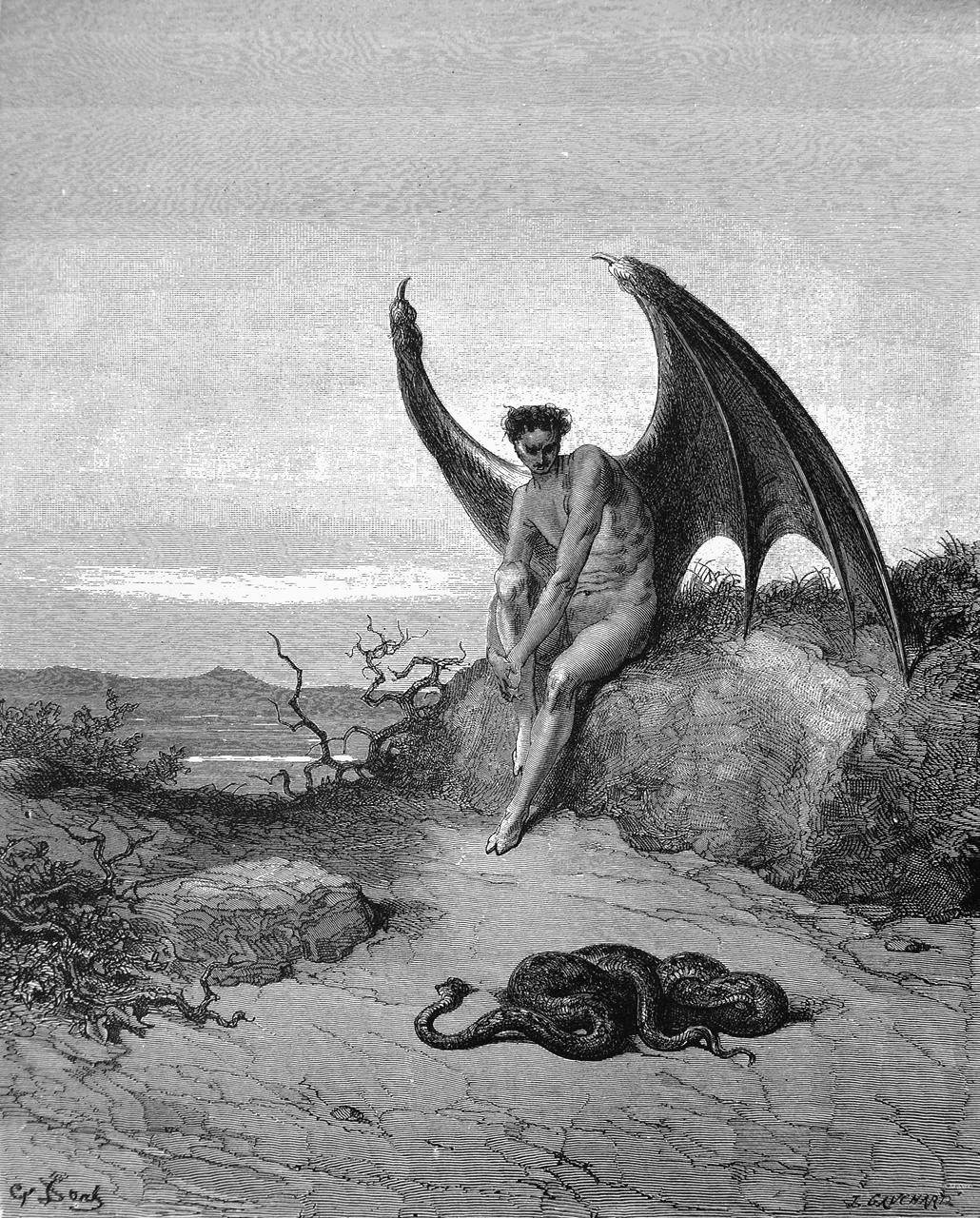

Beginning in 1692, more than 150 men, women and children colonists in Massachusetts were wrongly accused of witchcraft without evidence in what is referred to as the Salem Witch Trials. It lasted for a time before the excitement surrounding “witches” died down and courts annulled guilty verdicts. More than 300 years later, in the 1970s Americans put their peers on trial for practicing Satanism and its rituals. These trials also occurred without any solid evidence. The United States became obsessed with the menace of Satanism.

From the 1970s until the early 1990s, people worried about the presence of Satan in their communities. It began with fear of serial killers like Charles Manson. Some Americans wrote books, like Michelle Remembers and The Satanic Bible, detailing their experiences with Satan. The Exorcist and its subsequent movie’s claim that it was based on a true story influenced the way people considered Satan’s presence. Police were trained to handle Satanic cults. All of these publications and their frenzied media coverage made the average American believe that Satanic rituals were becoming a norm for a part of the population.

At the same time, there was a rise in need for daycare because of the emerging visual of the white woman in the workforce. Fact-checking site Snopes explains that this increased need for childcare in the period caused great anxiety among parents and encouraged a mistrust among care providers. This mistrust caused a rise in abuse allegations against daycare providers, with parents claiming that care providers were Satanists and forcing their children into their Satanic rituals. Some children were made to support such allegations.

While it may seem absurd that anyone would believe these claims, hundreds of people were accused, many were jailed, and one couple even stayed in jail until 2013. This pair, the Kellers, faced charges of sexual assault, serving blood-laced Kool Aid, cutting the heart of a baby out, flying children to Mexico to be raped, killing children, resurrecting them, and other allegations. They served 22 years in jail on the basis of the Satanic Panic. Prosecutors finally exonerated them in 2017.

The idea of stranger danger is also relevant to understanding the context here. This sort of shocking news spreads so quickly and so widely, so its relating themes do as well. Therefore, with the Satanic Panic, people learned to fear others, to be nervous in their own neighborhoods, and to not let anyone else watch their children. Other news at the time, such as the Tylenol murders of 1982, a man lacing his son’s Halloween candy with poison, and a rise in AIDS further intensified the fear of some unknown evil taking control. Because of the overarching, fear-mongering media, it became easier to pin something on another neighbor instead of inspecting the actual causes of unrest in America. It’s the same social dynamic that’s seen when going back to the Salem Witch Trials. Anyone who shows any signs of being “evil” or different appears to be a new predator, and people won’t hesitate to attack them.

Many times when a piece of fake news surfaces, it is because it is of national importance or concern. In 2019, for example, national politics have often been involved, such as in pizzagate and sharpiegate. In the case of the Satanic Panic, however, and also in the Salem Witch Trials, the focus was more on the idea of community. The Panic was focused not only on particular communities, but also on the idea of community itself in modern America. It was an era where Americans retained an idealistic view of the country and pushed back against apparent threats to it. They wanted to preserve a concept of a once “perfect” society, where all families lived peacefully and undisturbed in their neighborhoods. The idea that some people might be “evil” was new and scary, and so they pushed those citizens out.

While it may have been nonsense, the fearful results of the Panic’s media coverage contributed to a widespread fear of Satanic practices and a series of serious allegations. Psychologist Deborah Serani has examined fear-based media and its negative effects on consumers’ health. She explains that news outlets’ motives have turned more towards viewing “the spectacular, the stirring, and the controversial as news stories.” This kind of news then leads to competition between outlets. Who can stir up the most in their viewers? This dynamic led sensationalistic and fear-mongering “news” to become the norm. Some have critiqued this kind of news as being driven more by emotions than facts. Yet, because it is profitable, it continues.

It may be easy to brush off the idea of another event like this happening in future decades, but it may not be so far off the horizon. These events are more recent than they seem, and some are still suffering the consequences of them. What is perhaps even more important than what media outlets release is how consumers react. News channels and other media care about what gets them the most clicks, the most views, the most money. If Americans get so terrified into believing the fear-mongering stories that come out in the future, there will be more dire consequences. Sensationalistic media occurs at the cost of people’s lives, as shown in the case of the Kellers. News will continue to stray further and further from the balanced, unbiased journalism that many communities worldwide want it to be and yet another witch hunt will ensue to identify and punish the next enemy.