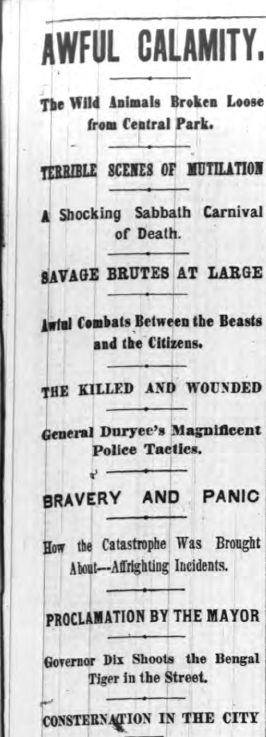

In 1874, the influential paper the New York Herald pulled a stunt that would diminish its credibility for decades. Whether in a test of its readers’ attention to detail, for the sake of pure hilarity, or just to generate revenue, the newspaper ran a story claiming that animals from the Central Park Zoo had escaped and were wreaking havoc upon New York City. The article claimed that 49 people had been killed and that hundreds more had been injured. At the very end, the article included a disclaimer which stated that nothing in it was true. But only diligent readers who finished the article would realize this.

Reports of the Central Park Zoo escape sent New York City intoa frenzy. Armed men took to the streets in search of at-large wild animals. Even the New York Police Department was prepared to take action. New York City’s sheer size allowed people to believe that there were wild animals at large that they could not see. New York City is large enough and so densely populated that, even if the chaos of a zoobreak were to occur, it would likely only affect a small percentage of the city’s population. Additionally, reports of such chaos would likely take days to verify, making the zoobreak story an example of a story that could only have fooled people in that particular location. The anonymity that a person can find somewhere enormous as New York City is so effective that the idea of animals invisibly running wild is plausible. The fact that the Lower West Side of Manhattan is not overrun with bears and tigers does not have to mean that the Upper East Side is not in chaos. In 1863, a highly racialized riot occurred in New York City. The “Draft Riots” were in protest of certain aspects the civil war draft, and resulted in at least 119 deaths. This was a major event in New York, but anyone who was not in Lower Manhattan would not see the destruction. Events that New Yorkers are not able to witness are not always considered false. It is easy for even major events to go unnoticed in such a densely populated area.

In 1874, newspapers were Americans’ primary news sources. As news grew more focused on generating revenue, advertising also became important. Maintaining popularity and selling as many papers as possible was as important as the job of keeping the public informed. As a result, some papers began to intentionally run falsified pieces. The ideal article was shocking enough to sell, alarming enough to warrant panic, but unlikely to cause real injury.The New York Herald pushed the boundaries of print-era clickbait and caused panic, but technically did nothing wrong. Any deception that occurred was because of inattentive readers, so if anyone believed the story, they could argue that it was their own fault.

Similar to the zoobreak, in 1938, some Americans mistook a radio broadcast adaptation of War of the Worlds for actual news. While the broadcast did not spark a panic as many believe, some Americans did believe that aliens were invading.The format of the broadcast was very similar to that of the Central Park Zoo piece. In both cases, the story mimicked the format of news, though they each included disclaimers. Without consumer awareness of these disclaimers, however, either could easily be mistaken for actual reports. This lack of attention to detail was enough for some Americans to perceive these stories as reality.

Other newspapers and media companies were quick to criticize and denounce the Herald’s article, calling it “intensely stupid,” and an “unfeeling hoax.” Some citizens attempted to put together a lawsuit against the paper, though since the paper had included a disclaimer, and broke no laws, there was no real case against the Herald.

The zoobreak article ultimately led to the Republican party’s adoption of the elephant as symbolic representation. In an illustration published by Harper’s Weekly the paper criticized President Grant for planning to seek a third presidential term despite the tradition since Washington of limiting himself to two. Approximately a week after the Herald’s hoax, Harper’s Weekly ran an illustration that depicted the Herald as a jackass. The jackass was shown as scaring other zoo animals, as they ran through the woods in Central Park. One animal, an elephant, was labeled “The Republican Vote.” The following week, the same cartoonist, Thomas Nast, again depicted the Republican vote as an elephant. Soon, others caught on, and the elephant became a common depiction of the Republican party.

Despite widespread criticism of the paper, the sales rates of the New York Herald did not drop after the hoax. The paper would continue to print until 1924, decades after the Central Park Zoo story. However, after torrents of criticism both from readers and other media outlets, the Herald did not pull such a prank again.

In the news world, perception is reality. If a reader perceives an event as a catastrophe, tragedy, or chaos provoking mess, the story becomes exactly that. In the case of the Zoobreak Hoax, it was only after readers perceived this story as news that they were able to treat fiction as fact.