For week one, I thought it made the most sense to start at the beginning to see how people have approached the topic of internet linguistics in the past. Because technology changes so quickly, “the past” is here being roughly defined as before 2012.

The materials for this week:

- Crystal, David. Internet Linguistics : A Student Guide. Chapter 1 pg 1-10

- Cook, Susan E. “New Technologies and Language Change: Toward an Anthropology of Linguistic Frontiers.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 33, 2004, pp. 103–15.

- Crystal, David. Language and the Internet, Cambridge University Press, 2001. Pg 6-23

- Squires, Lauren. “Enregistering Internet Language.” Language in Society, vol. 39, no. 4, 2010, pp. 457–92.

[full citations at the end of the post]

Let’s jump in!

Why is it important to study language on the internet?

There are two primary arguments that the authors I read for this week made about why we should study language on the internet.

Firstly, the internet allows us to study linguistic interactions in a unique way. Because the internet is majority text-based and often anonymous, users can withhold the visual or auditory markers of gender, age, race, and ethnicity that people take note of when interacting with people offline (Cook 104).

Secondly, technology is an increasingly omnipresent factor in our everyday lives. It’s good for us to understand it! By understanding it we can make more informed choices when it comes to internet use and management, both as individuals and in the public sphere (Crystal 2011, 7).

How do we talk about language on the internet?

It’s more complicated than you might think. One early choice was to refer to it as “computer-mediated communication” or CMC for short. However, as David Crystal asserts in Internet Linguistics, this term is too narrow – computers are not the only way we access the internet nowadays, so this term leaves out phones and tablets (2). Terms like “digitally-mediated communication” (DMC) or “electronically-mediated communication” (EMC) are more inclusive, but they are in fact too broad. This is because communication is not synonymous with language (1). Texting someone a selfie might communicate something – be it an emotion, information about one’s location, and so on – but it doesn’t involve using language.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, netspeak and chatspeak became seemingly common ways to refer to internet language. These two terms are not ideal for my purposes, however, since (1) they presume that all internet users are using English in the same way, and (2) they are tied to particular features that are seen as being emblematic of English on the internet. Lauren Squires expands on this in her 2010 article “Enregistering Internet Language”. Enregisterment is defined as “how a linguistic repertoire becomes differentiable within a language as a socially recognized register of forms” (459). In more accessible terms, it’s how a type of language usage becomes recognized as a distinct variety of language with distinct features. As Squires explains, “Netspeak” and “Chatspeak” are essentially social constructions of what “Internet Language” is thought to be, and the enregisterment of these terms was mostly done by people who were outsiders to the chatrooms and other online spaces where these nonstandard uses of English were occurring (466).

In my experience ‘chatspeak’ and ‘netspeak’ have now fallen out of fashion anyway and feel pretty dated (I can’t remember the last time I heard someone call the internet “the net”).

So how do we describe language used on the internet? Perhaps a term like “electronically-mediated language”, EML for short, would be helpful – and we could specify EME for when we’re specifically talking about English. But there is no singular way that English is being used on the internet, and I do worry that using a term like “electronically-mediated language” might imply some sort of homogeneity. In any case, “language on the internet” or “English on the internet”, especially with specifiers for specific contexts, genres, and demographics may be the most accurate (and most easily accessible) way to discuss how people are using language online.

Things to keep in mind as we discuss language on the internet

Although technology allows for rapid transnational communication, that doesn’t mean internet users don’t exist in a vacuum. Offline events may impact uses of languages just as much as new technologies or sites do, and we should avoid taking a “technological determinism” outlook and assuming that technology has an “inevitable consequence” on how users interact (Cook 108, Squires 461).

We should also be wary of generalizations, as is true in most any field. Internet users come from a variety of backgrounds, so thinking of nonstandard language use as being primarily driven by youth or by uneducated people may cause us to overlook what is objectively occurring (Cook 109, Squires 479-480).

How do we discuss different aspects of language on the internet?

In Language and the Internet, David Crystal lays out some different categories for language features:

- Graphic features: these describe how language is presented and organized, and includes things like font, page design, spacing, and color.

- Orthographic/Graphological features: these describe how a language utilizes its writing system, including capitalization, spelling, punctuation, and any type effects (bold, italic, underline, etc).

- Grammatical features: these describe the grammar of the language, like its syntax (sentence structure), morphology (word formation), and word order.

- Lexical features: these describe the vocabulary being used.

- Discourse features: these describe the larger organization of language, like how a text is structured, how it uses coherence and relevance, how it structures paragraphs, and how it progresses and transitions between ideas.

He also adds two other categories for spoken language:

- Phonetic features: describes how speech sounds, and includes tone of voice, quality of voice, volume, and so on.

- Phonological features: describe how sounds create meaning, and include features like the distinctive use of vowels and consonants, and how one uses intonation, stress, and pauses.

The first five categories will be the most helpful for me this semester.

How does language on the internet differ from offline language?

The internet is a very different forum compared to traditionally published written works. But whether there are specific differences between language on the internet and spoken and written language in other contexts is still somewhat unclear. One’s individual context – the websites being used, the communities one is joining, and so on – will impact how exactly one uses language online, and each online community will use language a bit differently. The language one is using online may not be radically different from the language one uses while speaking and writing offline.

One thing that has not changed in the twenty years since Crystal wrote his 2001 article is that users tend to absorb much more language than they produce, and the internet is “almost entirely dependent on reactions to written messages” (18). An internet user is an unseen audience member taking in a large amount of language, unlike offline face-to-face conversations. But unlike traditional written media, the internet is also interactive. There is the potential to comment, to interject, to edit or correct. Some people have described internet language as a “hybrid variety of language” because it combines features traditionally associated with spoken language and written language (Squires 461-462).

One commonly cited element of internet language is its vocabulary and writing style – lingo, slang, abbreviations and phonetic spellings. However, the extent to which there is strictly internet lingo is debatable. Abbreviations, acronyms, and nonstandard spellings have long been a part of written English texts, and slang and writing conventions can differ wildly between sites, genres, and age groups. For instance, apostrophe usage can vary greatly between individual users, as can patterns of capitalization and frequency of acronym usage (481-482). Internet language is not a singular variety of language, but rather an umbrella that encapsulates many different ways that people write online.

Reflections

One fascinating thing from this week was seeing what from these older pieces felt incredibly dated and what held up as still relevant.

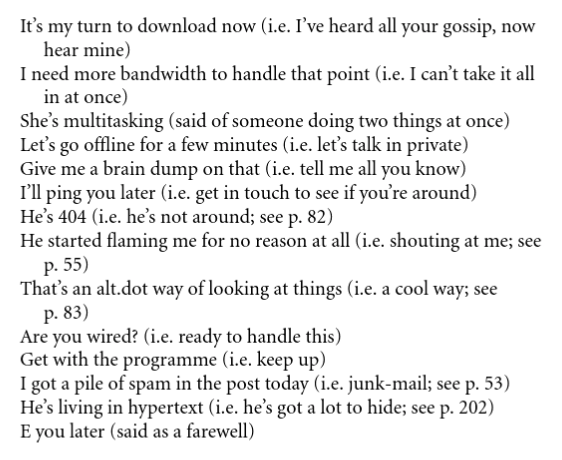

Take, for example, these examples of “terms from underlying computer technology” bleeding into offline conversations, from page 19 of David Crystal’s 2001 book, Language and the Internet:

I recognize three of these terms as they are used in the list – “bandwidth”, “multitasking” and “get with the program”. The rest feel incredibly dated. As with all slang and new terminology, the number of words/phrases that remained within the general lexicon of English speakers is far smaller than the number of words and phrases which were short-lived and remained within niche groups.

Let this be a reminder to us that the observations we make about language on the internet apply to a specific context! What’s true five years ago may not be true today, and the language we see on Twitter may not reflect the language we see in texts, emails, or Facebook.

See you next week, where we’ll look at how technology shapes online writing and how it may shape the language and writing conventions of its users.

References

Cook, Susan E. “New Technologies and Language Change: Toward an Anthropology of Linguistic Frontiers.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 33, 2004, pp. 103–15. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25064847. Accessed 15 September 2022.

Crystal, David. Internet Linguistics : A Student Guide, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011, pp. 1-10. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/smith/detail.action?docID=801579.

Crystal, David. Language and the Internet, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp 6-23. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/smith/detail.action?docID=201947.

Squires, Lauren. “Enregistering Internet Language.” Language in Society, vol. 39, no. 4, 2010, pp. 457–92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40925792.