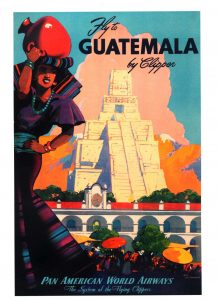

The timeline below shows the view of Latin American women that U.S. advertising campaigns presented during the twentieth century. This gaze is extremely colonial, one in which Latin American women are exoticized and commodified because of their mestizo heritage. The concept of the Mesoamerican “sensuous and eroticized mulata” and indigenous woman, however, is not new.1 Hernan Cortés’s courtesan/wife/translator, Malintzin, is the epitome of this sensual stereotype. Because of her involvement with Cortés, Malintzin (commonly referred to as La Malinche) is seen as an ethnic traitor, preferring to conform to the white colonizer’s gaze instead of defending her people.2 There are traces of Malintzin in the campaigns above, where the women of Latin America, stuck somewhere between complete assimilation and indigenous sensuality, become tempting offerings to tourists from the United States.

How has this colonialist gaze affected contemporary Latin American women? According to Andrew Canessa, these women “all participate in a (neo)colonial economy of desire and consumption in which the Western sovereign individual can seek to satisfy his or her desire for the exotic, the ‘Other,’ and the premodern on a very uneven playing field. And yet, despite these hierarchies and inequalities, many of these contributions demonstrate that there is a capacity to subvert the gendered colonial model and carve out new spaces in which the contributions of women are publicly valued and can be translated into real and not simply symbolic gains.”3 Women from Acapulco, where indigeneity is often a sense of shame, can migrate to Baja California to sell their artisanal crafts to ethnotourists, resulting in a sense of pride and productivity.4 From Baja California to the Andes, Latin American women capitalize on the image constructed by U.S. advertising campaigns during the heyday of Latin American tourism. Although this image can sometimes be dehumanizing—leading to paths like prostitution and domestic abuse as their male counterparts feel threatened by their heightened autonomy—, Latin American women continuously convert their cultural capital into economic capital.5

- Andrew Canessa, “Gender, Indigeneity, and the Performance of Authenticity in Latin American Tourism,” Latin American Perspectives 39, no. 6 (2012): 110.

- Cordelia Candelaria,“La Malinche, Feminist Prototype,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 5, no. 2 (1980): 1, doi:10.2307/3346027.

- Andrew Canessa, “Gender, Indigeneity, and the Performance of Authenticity in Latin American Tourism,” Latin American Perspectives 39, no. 6 (2012): 114.

- Andrew Canessa, “Gender, Indigeneity, and the Performance of Authenticity in Latin American Tourism,” Latin American Perspectives 39, no. 6 (2012): 113.

- Ibid., pp. 110.