The Early History of Death at Smith College

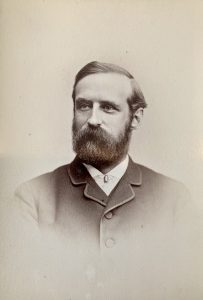

Death continues to be highly unusual on campus. During the first eight years, only one student died of 500. Seelye was swift in ameliorating concern, writing that the young woman “had the seeds of a fatal disease when she entered and only remained in the college ten weeks”(59). Regardless, the year following this report would prove more trying. Only a few days before the beginning of the Fall 1883 term, Professor Moses Stuart Phelps had accidentally shot himself while hunting in the thick Maine woods. The young professor was only 34. Five years earlier Phelps had been appointed to teach “Moral and Mental Philosophy” to the new school in 1878, a now-obsolete study rooted in theology. Standing at nearly 5’11 he was a handsome man, with oak-colored hair and beard, his thin face accentuated by deep grey eyes. Very soon after a student herself would die, the tragedy this time occurring as a drowning at a seaside resort. It proved too much to bear for the small campus, and three female professors would all resign within the next few months due to the emotional pain (61).

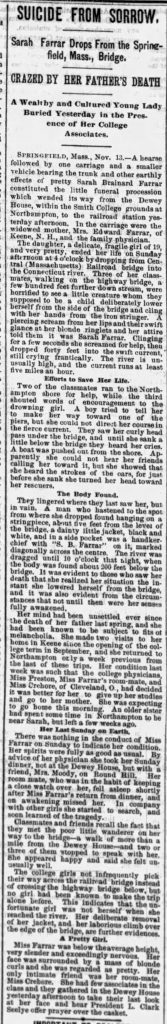

The first known suicide on Smith College’s campus occurred on the 11th of November 1888, by a first-year named Sarah Brainard Farrar living in Dewey House. Despite the event being particularly traumatic to the campus, all that is known about her in the Smith College archives is her empty grade page, silent in a tomb brimming with the hours and letter-grades of her living classmates, and a notecard referencing her suicide in the “Disasters” archive box.

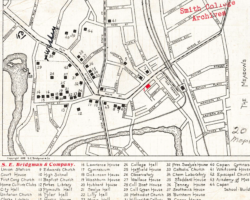

Researching local papers, a larger story is illuminated. Spending less than a month on campus, the nineteen-year-old Sarah was known as an anxious, depressed girl, frequently taking trips home due to the sadness of her father’s recent death. Papers describe her as particularly pretty, with blonde curly hair, though thin from nerves. Her only friend on campus was her roommate, a girl named Mary Louise Crehore. Sarah ended her life walking to the Connecticut River bridge (today the Calvin Coolidge Bridge) connecting Northampton to Hadley and jumping. Two twelve-year-old boys and three Smith students on the passenger bridge below witnessed the horrific event and described to the police how Sarah had attempted in vain to climb back up via her coat, screaming as her strength failed her and she fell below.

Sarah had not been on campus long enough to make any friends, but her body was brought back to Dewey House for a brief memorial from the local undertaker in town. Seelye arranged a viewing of her drowned body in the house parlor, read a sermon, and helped transport her body to the train station to laid to rest in her home of Keene, New Hampshire via local hearse—her mother in a carriage behind it.

While this occurred while Laura was finishing her high school education, her older sister Florrie witnessed the commotion on campus as a new junior. We have no records of how people on campus reacted to the death Sarah, but it is undeniable that Florrie would have remembered this while grieving for her sister only a few years later.

The Early History of Wallace House

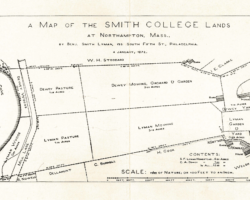

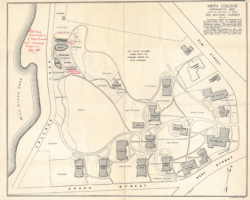

By the late 1880s, a change could be seen on campus. Brought on by the growing popularity of the school, there seemed by Seelye to grow year by year to be “a larger proportion of students who were perhaps more inclined to amusement than study.” The school had outgrown its four small houses on campus, and more than one-half of students were resigned to live off-campus in boarding houses run by Northampton women. Laura’s sister Florrie lived in one of these off-campus houses all four years of her education, residing in Stoddard House on Elm Street (located today where the Alumnae House is). Keeping order was proving difficult. A new dorming house had to be built on campus: Wallace House was thus born.

Wallace House opened for the fall semester of 1889, Laura’s first year. It was named in honor of Robert Wallace, an original Trustee of the college. It was situated just west of St. John’s Episcopal Church, today part of Seeyle Lawn that is in front of the present location of Dewey House. Neither Seeyle Hall nor Neilson Library had yet been built, and thus campus was small and intimate. Female professors often roomed in houses with their students, and diary entries attest to the rush of finishing a paper and having to run downstairs to turn it in. Wallace House was the residence of English professor M. Elizabeth J. Czarnomska, a young woman rumored to be from the Polish aristocracy and a personality to match. The other older woman in the house was the Housemother, a general well-keeper of the girls named Sarah Robinson.

Female Suicide in the 19th Century

It is believed by experts that for every completed suicide, there are seven that fail. Since the beginning of documented history on the subject, and regardless of where in the world, men have unilaterally been more successful than women in the act (543). Studies note that while women attempt suicide at a rate of 2.3 times more than men, men are 2.3 times more likely to be successful (541).

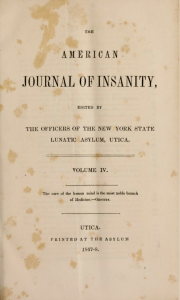

In the 19th century, female suicide was seen as even rarer. In 1848, the American Journal of Insanity published a small report on the statistics of suicide in New York state, detailing the methods of death by sex. Only around 1 in 4 (25.5%) of suicides were female, and the method of their deaths was in larger percentages from hanging, drowning, and self-poisoning—compared to the self-inflicted gunshot wounds and throat-cutting overwhelmingly found in men. In 1861, the New York Times reported that only about one out of four suicides in New York were completed by females, lower than in major European Cities. Their reasoning was the ease of divorce for women in the United States, as they concluded that “a large proportion of female suicides attribute their act to domestic unhappiness.”

With the transformation of mental illnesses from a moral failing to a medical anomaly during the 19th-century century, suicide transformed from a crime to an illness. During this period, writers such as William Knighton argued specifically that suicide was a distinctive masculine illness, due in part to the more violent methods the successful male suicides employed. In 1881, in his article Suicidal Mania, Knighton himself would write that “Women cling to life much more strongly than men” (537). This was bolstered by the biggest names in sociology at the time, such as S.A.K. Strahan, Henry Enrico Morselli, and Émile Durkheim who all wrote of the “masculine” act (Deacon 7).

Despite the “maleness” of suicide, modern women’s historians have found ample evidence that while perhaps still at a lower number than men, many female suicides were suppressed by family or community members in the official death certificates. One example, a thirty-four-year-old brothel owner named Clara Dudley attempted suicide with an excess of morphine. She failed and died five days later from pneumonia brought on by her attempt. Her death certificate states the cause as “pneumonia,” despite the numerous documented suicide attempts in her past (545). Due to the less violent means of death women tended to choose, this situation (as well as the other stated above) should remind us of the under-documentation of female suicide.

Despite medicalization, suicide was still deeply feared and taboo, especially for women. By the mid-19th century it was believed that mental illness was potentially inheritable, though by “a weak family and vice committed by ancestors.”

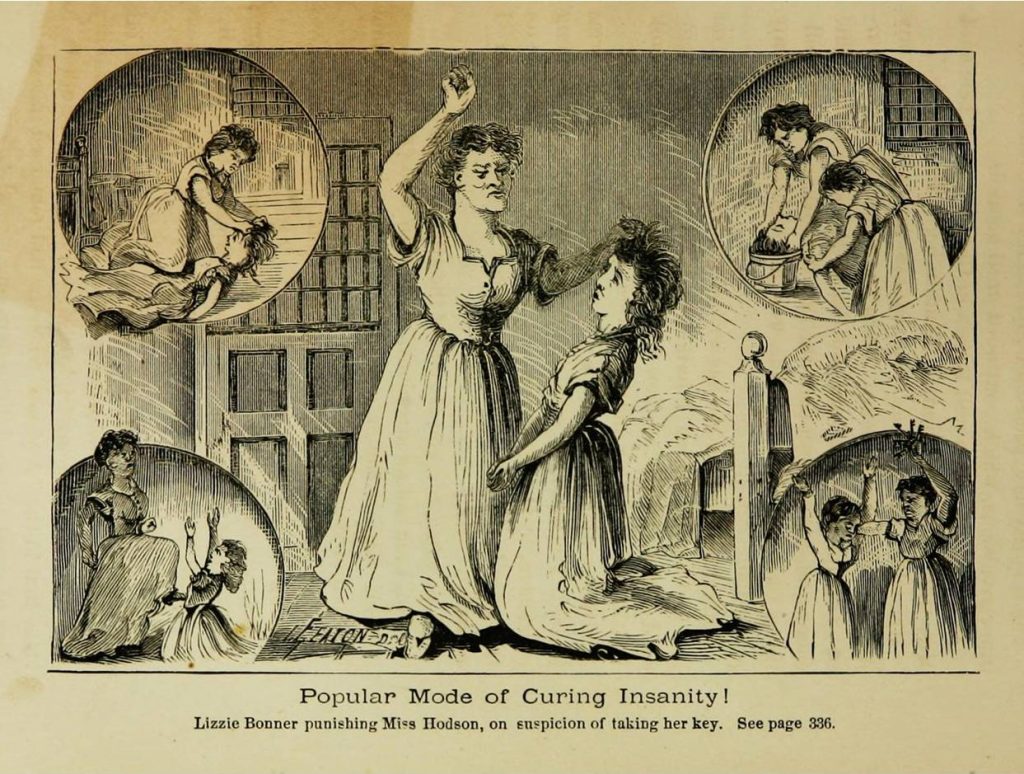

In 1868, Elizabeth Myers published her account of her three years imprisoned in the Jacksonville Insane Asylum, forced by her husband when they did not share the same political beliefs. Entitled Modern Persecution or Insane Asylums Unveiled, Myers documented the everyday horror of abuse at the hands of the hospital. Only four years before Laura’s death in 1887, the journalist Nellie Blye published her groundbreaking exposé Ten Days in a Mad-House, documenting her time feigning insanity in order to be admitted into Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. She documented the terror firsthand as well, including the dangerous ice baths, mental and physical abuse, and spoiled food she was forced to eat. Surely, this would have been on the mind of Laura. A mental hospital would not have helped her hurting soul.

Despite this “masculine malady,” the image of the drowned woman proliferated in the Victorian world. From John Everett Millais’ Ophelia to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, to George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss and to the later Kate Chopin novel The Awakening, drowning came to be understood as the logical end to a fallen woman, so much so that simply an image of a woman next to a body of water became shorthand for suicide (Deacon 10). Historian and theorist Barbara Welty first proposed the idea of the “Cult(ure) of Domesticity” in her seminal 1966 article “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” In it, Welty illuminates the domestic frame of mind that Victorian, middle-class women operated in, defining their existence by the values of piety, purity, submission, and domesticity. “The loss of purity,” Welty writes, brought about “madness or death,” with the popular mindset being “Death Preferable to Loss of Innocence” (144).

Josephine Dunlap Wilkin, a first-year student when Laura died, wrote pages to her mother about the incident. She relayed the gossip around the school, writing that

It is now known that she did not confess of her own accord, but that the janitor caught her in his room, and told the president and on his interviewing her she confessed that she had taken things. In her diary she wrote that she had done a dreadful thing, too horrible to write, and later that she should drown herself in Paradise.

The only trace of Laura’s last note was written and published in the local newspaper:

I have just done a dreadful thing, it is too horrible to write of here, and why I did it I do not know. I have brought disgrace upon myself and cannot survive it; I shall drown myself in “Paradise”; do not search for my body.

Under Welty’s definition of womanhood, Laura had clearly transgressed. A pure woman did not steal. While we know that Laura was caught stealing, we do not know the nature of why. While her close friend revealed that “madness” ran in the family, not even her friends and family could find a reason for the thefts, nor did they note her having a history of kleptomania. Papers reported that a few days before her death that Laura complained of a lack of appetite and inability to sleep, resorting to drug powders to sleep.

We can only guess at the things that were “too horrible to write”—perhaps a romantic or sexual affair of some kind or simply bad dealings, the money a ransom to keep quiet or to pay for her problem to be “fixed.” Given the family history, Laura was most likely beginning to develop Bipolar Disorder—an illness that manifests in an inability to sleep, eat and sometimes even paranoia and hallucinations.

Unfortunately, we will probably never know the true answer. Until Laura’s diary emerges from the sweaty basement, or new letters surface, Laura is mum—and that’s probably what she would have wanted. In the world she left, Laura was still (almost) pure.

Footnotes