What I set out to do was impossible: I wished to raise the dead.

In mid-September 2021, I lost my third friend to suicide. His name was Mick Beyer. He was 20. He was my best friend during my senior year of high school. I don’t know how he killed himself. My mourning is arrested; my grief at times limitless. And like my other two friends, he didn’t have a grave. They all died too young, and death (and headstones) are not much in vogue these days. They’re cremated and left in the family homes that they tried to escape.

I began this project looking for deaths on Smith College campus. I’ve always enjoyed true crime, and I wished to recreate the spooks of missing girls and murders so close to home for an audience of eager Smithies.

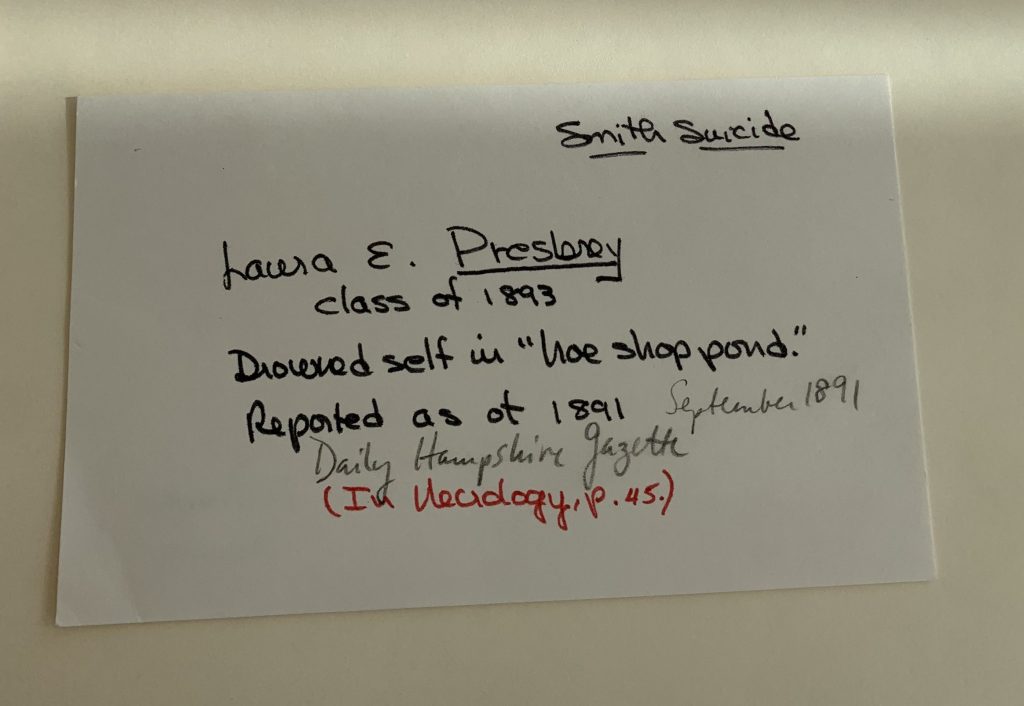

But as time (and research) wore on, I found myself focused on the most underdocumented of my girls, a young woman whose entire life was reduced to a few scanned newspaper articles about her disappearance and death, and three photographs. Even the notecard in the “Disasters” box in the Smith College Archives had the month of her death wrong—it was overwhelmingly clear this student was forgotten. The only thing of note was her death.

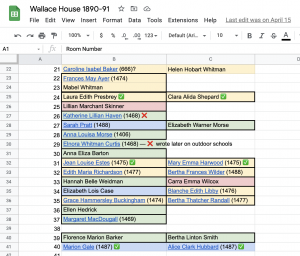

After combing through every student diary, epistle, and history—after recreating Laura’s entire house floorplan and placing each student where they roomed, I still had found nothing about her. I searched every file of her housemates and her fellow banjo club members. Nothing.

My Hail Mary was visiting Taunton, the small town outside Boston where Laura grew up in. I knew her older sister Florence had donated most of the photos containing Laura to the Smith Archives in 1940 from her signature on the back, and hoped that the family photos would be in the Old Colony History Museum, the reservoir for Taunton history. None of Laura’s sisters married or had children. I was helped by the wonderful curator of collections there, Bronson Michaud in this search.

We began looking at the microfilm for the Taunton Gazette. I went through day by day starting with her disappearance, and there was nothing. While the entire Eastern Seaboard wrote article after article of the salacious drama, her hometown had silenced it. Only on the day that her body was found was brought back to Taunton was there a description of the story, stuck on the very last page. Laura’s father had wanted to hide it.

We next searched photographs for the Presbrey family, both in a database and out, with nothing. Bronson searched for a Presbrey diary. Again, nothing. I remembered that Laura was a student at the academy the museum was now housed in—we succeeded there, finding a few graduation pamphlets with Laura listed in the merriment and a single group photograph containing a young Presbrey daughter, either Florence or Laura. Not only did I still have nothing of Laura, I realized with a lurch I had absolutely nothing of her mother, Sarah, either. Dr. Silas Presbrey, a town hero with a forgotten wife. Bronson commiserated with me at the lack of evidence of women’s lives in archives. Laura had slipped through the cracks again. I had no names of friends, or of interests; I still do not know if she was even funny.

I cried in the room when Bronson left. I knew our search was in vain. Laura’s town had failed her, both immediately after her death and in the years after. The family photos were not here. Her family had wished to hide the shame of it.

As I left her old schoolhouse, I decided to look in the portrait gallery. I looked at the town founders and the stately leaders of yore, when I saw a familiar face. Two small miniatures hung side by side. They were of Florence and her father, Silas. The tag read that it was their sister Clara who had painted them, and by the looks of it, about ten years after Laura’s death. The family was together, but again, no Laura. My heart was fuller, but still aching. I had one last place to visit.

Mount Pleasant Cemetary in Taunton is beautiful. It is a rolling garden cemetery, a type defined by its beautiful trees and monuments. One can easily believe they are lost in it, the hills easily obscuring the rows of houses around it. And so I entered and began my search. I took my shoes off, walking up and down the hills, finding Presbrey family after Presbrey family, but not the one I wanted. I was desperate, my feet bare and black, the minutes passing by. I had gone through almost the entire left side with nothing. I had a train to catch soon.

As I made my way down the steep top hill, I found her. The blunt, simple obelisk of Laura Presbrey’s family was within my sight. I began to cry, as one does. I spent only 20 minutes there, all the time I had, and mourned finally for my friends and Laura. I laid with her footstone, staring at the bare-fingered trees above, something I had done for hours with the death of my first friend Emi five years previously. I looked up, begging my friends and Laura for some sign, for a miracle I could grasp onto in my loneliness.

Wind. Beautiful wind. I felt it around me, shaking the fingers up above, just subtle enough a sign it could be nothing. I like it like that.

Meditating in my grief, I saw the beauty of this abandoned cemetery. I was alone with the thousands of forgotten souls, peaceful and quiet. I felt the sadness, but more importantly the profound calm of death. We would all be forgotten one day, and it was beautiful in the most natural way possible.

As I made my way back home to Smith’s campus, I was struck finally by the futility of my project. What I wished to do was in vain. Completely. I thought somehow by finding Laura I could bring her (and Mick) back to life—an impossible goal. I had spent hours with my therapist trying to parse this problem, many nights left in a huddled mess over the reality that my friend was now forever beyond my reach. Laura had fallen through the cracks of history, just as Mick, and me, and you would one day too.

Two days later, on the night of my college’s Senior Ball, I did something terrible. The culmination of my PTSD and lack of support from Smith led me to an act I cannot utter online. I remember the grief and guilt that immediately flooded my poor body, still in my ballgown and fur coat. I was hysterical. I knew then Laura’s electric shame. I saw only my death before me. I ended up in the Cooley Dickinson Behavioral Health Unit for six days.

While recovering, I met others with similar stories as us. I ate breakfast with suicide survivors, with addicts, former prisoners, moms and dads, sisters and brothers.

A spoke with several nurses and patients about my project. I told them the story, and I told them how it ended: she stole money she didn’t need, she couldn’t sleep, she felt horrible for her acts and drowned herself. “She’s manic,” one nurse told me immediately. “She couldn’t sleep. She’s impulsive.” I looked up at her, silently begging for more. “There’s a story there. There’s more to this.” I knew it too.

Routinely the other patients and I would bond over our “lifting” pursuits, the random things we stole for pleasure during our manic episodes before we were prescribed mood stabilizers. “I stole books mostly,” I confessed with a smile, as I always do. Not many mad girls steal what I did. “Hundreds of dollars worth,” I continued, “and vintage clothes.” Another girl would start up: “I stole the dumbest shit. Funko Pops.” And so we would go on, laughing at our mania, reveling in the past God-like joys we knew before landing ourselves in this prison.

Adjusting to the outside world after my week in the hospital has been difficult. The night I returned to campus I sobbed on the bank of Paradise Pond, on the road near the Japanese Garden. I thought of my friends in the hospital ward I’d never see again, and then I thought of the cruel injustices that put me there to begin with. I thought once more of the original sins against me and burned. How I wished to have had the courage to kill myself! In my beautiful blue dress and fur, I imagined the look of my cold body. I dropped my feet into the water. I understood Laura’s death then—how the freezing water was not as strong a pain as the incalculable shame and grief that had already consumed us both.

But I did not wish to die, not truly. I still have life within me, and I know the immeasurable beauty of it. And Laura’s story to share.

So, who was Laura? Well, she’s the patient down the hall in the hospital. She’s the girl crying on the bank of Paradise Pond. She’s the student ignored by the administration and suffering, the girl suddenly missing from class. She’s the daughter you love, the sister you love, the dead best friend you ache for, the memory that haunts you until you die. She laughs. She smiles and loves.

That is Laura.