On a cloudy, hot summer Thursday, a baby girl was born.

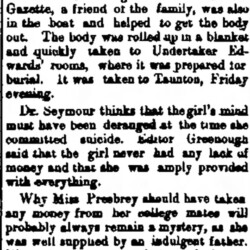

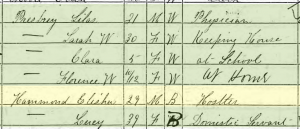

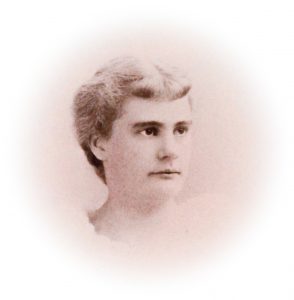

The temperature refused to dip below the 70s—even in the dead of night. Up above, the clouds withheld the family’s sweat as the new Laura Edith Presbrey was held (and screamed). She was the youngest and last child of Silas Dean Presbrey and her mother, Sarah Williams. The two experienced parents would hold on to her the best they could for the next 20 years.

The temperature refused to dip below the 70s—even in the dead of night. Up above, the clouds withheld the family’s sweat as the new Laura Edith Presbrey was held (and screamed). She was the youngest and last child of Silas Dean Presbrey and her mother, Sarah Williams. The two experienced parents would hold on to her the best they could for the next 20 years.

Laura was comfortable.

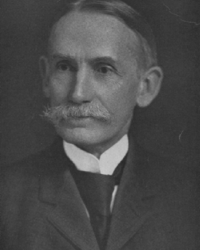

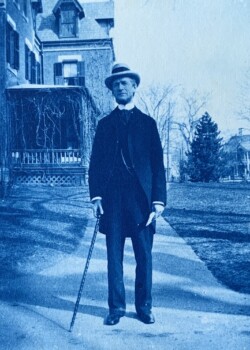

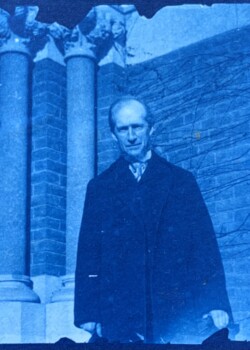

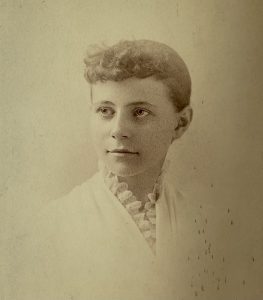

Her father had been born in Taunton, just as his parents before him had, and so on and so forth. The Presbrey family was of some heft to the town, and Silas was well aware of it. He was a relatively tall man, standing at 5’11, with a reddened-face surrounding blue eyes. He had gone to his public high school before going on to graduate from Harvard in 1860 at the age of 22. Coming back home, Silas pursued studying medicine with a local physician, quickly being accepted into Harvard Medical School in 1861. He took a detour though, devoting the next two years of his life to being the principal of the local public high school he had once attended.

It was during his first semester at Harvard Medical School that he married a woman by the name of Sarah Briggs, a twenty-four-year old from a small town nearby whose family worked in blacksmithing. The Briggs’ were another prominent family of the area, with ancestors able to trace back their lineage hundreds of years to the area just as his could. It was not unusual for descendants of random Presbrey’s, Briggs’, and Dean’s to live and work next to one another, and it was known that everyone was related to everyone in one way or another. The two must have met sometime before, either through church or school, as both had been educated at the local Taunton public high school. Two years later though, in 1865, Silas had finally graduated from Harvard Medical school—with a baby already at home. As the Civil War sputtered to an end, Silas set up his own private practice in Taunton and was noted for his kind bedside manner toward his patients.

Laura’s eldest sister Clara was born just shy of 7 years before herself while her father was still studying at Harvard. She stuck out from her sisters and father, with a large nose and brown hair, her skin a few shades darker too. Despite this, she had the same blue eyes of her father and two sisters. Clara was a gifted artist, and as she grew, it became apparent she should study it. It does not seem she studied at Bristol Academy, the local Taunton private school as her two younger sisters attended, but instead pursued artistic training nearby. At age 18 she won the first place prize in watercolors at the Bristol County Fair, going on to study painting at Radcliffe College.

Laura’s second oldest sister was named Florence. Going by the name “Florrie,” she was three years older than her, and the two shared a rope of dirty blonde hair and blue eyes, with pale skin betraying the pink underneath. The resemblance between the two sisters was shocking; both were almost exact copies of their father. Like Clara though, Florrie stood at 5’6 tall.

We do not know how close Laura was to her siblings, but it must be said that all three sisters shared their birthdays in a single week in late August. Their poor parents must have not only dreaded the immediate costs of cakes and presents but been relieved to get it done in such a quick turnaround.

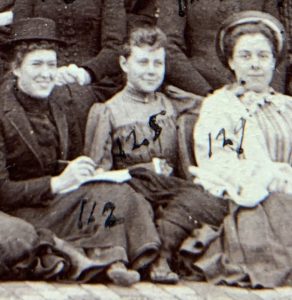

Laura studied at Bristol Academy, a small private school her father had recently been placed on the Board of Trustees for. It was about half a mile from her family home, and across the street from the church they attended, the Unitarian First Parish Church. A photo of the class of 1880 shows a Presbrey on the far right hand of the first row. Either Florrie or Laura, it is clear Silas enrolled his daughters as early as possible to prepare them for college: the little Presbrey girl is the smallest and youngest girl of the large group.

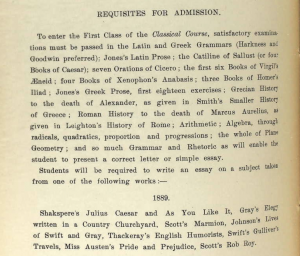

It was at this school that Laura studied endlessly for the Smith College entrance exam, a test that would occur over the course of an entire Summer weekend. While attending, Laura studied the everyday intellectual pursuits of mathematics, science, English literature, and history—with the added emphasis on a Classical education. The study of Classics entails the world of Ancient Greece and Rome, requiring knowledge of both languages, their respective history, and often the literature surrounding it as well. The study of classics as an education cornerstone can be traced back to the Middle Ages, and has long been entwined in Western thought. Following European schooling tradition, all elite colleges in the United States during this period still required a backbone of the study to be considered for a degree, including Smith College.

It is obvious then that Laura slaved tirelessly at her studies. Looking at future Smith grades, Laura was only slightly more adept at Ancient Greek than Latin, and much more so with the modern language of French. At the 1887 commencement ceremony (only one year before her own graduation), Laura played the role of a servant and cook for a French-language, five-act play, accurately predicting the stellar achievement she would obtain in this study two years later at Smith. For her graduation though, Laura wished to show off. She prepared, night and day, for her recitation of the famous 1830 rebuttal by Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster, a speech in response to Robert Hayne about the need for a united government under the threat of future slave-owning lands out west. Laura translated this speech into Greek, memorizing and orating it not only for her graduating class, but her family, and town on the hot and humid July evening.

Despite Bristol Academy’s strict segregation by gender, young women graduated at the same rate as their male counterparts, in some years—such as Laura’s—overwhelmingly so. Bristol Academy seems to have had three courses available for their students to pursue, a “Business Course”, an “Academic Course” and finally, the “College Preparatory Course.” Both Laura and Florrie received their high school degree in this last course, needing the specialized training to pass the grueling Smith College entrance exams.

In 1889, Smith College offered three different Bachelors degrees, each based on a different path of study. They included the Bachelors of Literature, a Bachelors of Science, and the most sought after—a Bachelors of Arts—a degree based on the study of Classics. Laura decided early to pursue this last one, devoting hours to studying her Ancient history and languages.

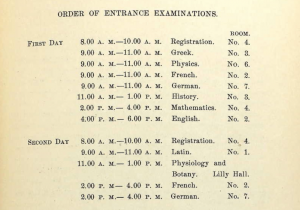

After a day at school, Laura traveled to Northampton on the evening of June 19th, only eleven days before her high school graduation. She was ready to attend Smith’s grueling yearly entrance exam. Laura would have made the 150-mile journey by train, perhaps with an aunt or uncle at her side so her father could keep up with their town’s medical needs. The nervous teenager would have stayed at a boarding house or hotel in town, tired from her journey but eager to meet other girls about to embark on their exams. Doubtless, she would would had studied as much as possible, running over her preparation papers with a new friend and remembering the words of advice from her sister on what would be asked of her on the small, imposing exam paper. She had been told to expect to be tested in both Latin and Greek grammar, each’s history, mathematics (algebra and geometry), and write an essay on a number of potential English literature pieces.

Laura woke up early the next morning. Walking into College Hall at 8 am, she had registered and began her Greek examination soon after at 9 am. As she finished, she prepared for the 11 am task: Ancient history. Going outside for a quick break, Laura went back to her seat in the same room. It was growing hot. After two hours of remembering scenes from the Peloponnesian War to the bloody Gallic Wars, the poor teenager had an hour’s lunch break. She approached her fellow students in a daze outside the red-brick school building, trying to stay cool on the grass under a tree with her compatriots. She was just relieved she was almost halfway through.

Math soon started, thankfully in a new room next door. By the last hour though, the heat outside was growing unbearable. She still had an English essay to tackle. By the time she had finished calculating geometric angles going outside seemed torture. She waited inside for English, moving once more to another room. It would have been lonely had she not seen the same girls in each classroom. She prayed she’d see them again in the fall.

It was still light out as Laura left College Hall for the day. The seventeen-year-old had been testing for a total of 6 hours.

Sunday morning began much as the day before. She registered, took her seat in another room for the last time, and did her best in Latin grammar. The years of training had been good to her. Though not as polished as her Greek, Laura felt sure of her outcome.

After brutal exam after brutal exam in the oppressively humid classrooms, Laura walked out with the news she had been hoping for.

She had been accepted into Smith College as a member of the class of 1893.

As Laura packed for her first semester at Smith, her mother Sarah looked on sadly. The young woman was the last of her children to leave home, though she knew she couldn’t complain much—Clara had come home in one piece and kept her company, and this year Florrie would graduate. She wondered when her little bird would marry, and if it’d be one of those Amherst or Yale men Florrie always wrote home about.

She also knew nothing ill would come to her by the likes of God. Smith was a deeply Christian institution, and she calmed at the thought that her two daughters would enjoy daily worship, readings, and study of the Bible. The family was Unitarian, but no attempt was made to change the denomination of its students. Rereading the booklet, Sarah smiled at such a liberal institution.

She also knew Laura would be cared for physically. Smith employed a female physician, a Dr. Grace A. Preston. Grace was one of the first graduates of the Smith, receiving the first of two medical degrees from Boston University in 1886. Originally wishing to be a missionary doctor, Grace was able to successfully advocate to be the school’s first physician. She was able to be seen free of charge by any Smith student or faculty.

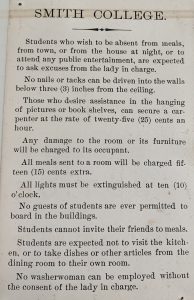

Sarah and Silas had read the Smith handbook and planned accordingly for the expenses. They sent the $10 to the college to secure for Laura a room to live on campus as her sister was doing (the other hefty $240 added to the $100 tuition bill was to be paid in increments later). The relatively large cost of living allowed Laura a furnished room, steam heating, and gas lighting, and only the necessity to make her bed. Maids lived in each of the houses upstairs, attending to the student’s household cleaning needs just as the help did around their own house.

Like many upper-crust Tauntonites, the Presbreys employed two maids. Girls had come and gone, mostly newly immigrated Irish girls looking for a meager living, but Sarah thought back to Elisha and Lucy Hammond. The African-American couple had come into their lives in the years after the Civil War, marrying in Taunton in 1862 and looking to start a life for themselves in the town they called home. Free-born blacks—while certainly not a majority in Taunton—nevertheless had a presence and history that can be traced back to this day. The newlywed Presbrey family took the couple in as boarders to help pay for their growing family, and both parties benefitted. Elisha worked as a pipe-maker, a hostler, and other odd jobs as Lucy worked a domestic life with the Presbrey’s.

It worked. By 1880, the Hammonds were homeowners in Taunton. As Clara, Florrie, and Laura grew up, the memory of the free-born couple in their childhood would have certainly passed their minds.

Laura began her first year in the brand new on-campus boarding house—Wallace House. As one of just fifty-five students chosen to live in the new house, Laura was excited. She could smell the new paint, feel the clean and beautifully polished wood—and remember the pamphlet’s stern words about no nails in the wall. With the help of local men, Laura’s empty trunk made it to the top floor, in large rooms next to the servant’s quarters.

Back down on the second story, Laura settled into her room, getting to know her new roommate, a girl from an even smaller town than hers named Clara Shephard. Clara was born and raised in West Bloomfield, a farm town in Upstate New York with a population of only around 1400. For the first decade of Clara’s life, her father had made the family’s living as a farmer, her mother staying home to take care of her and her older sister. They were able to employ a servant though, a second-generation Irish teenager, making ends meet by keeping a boarder as well, a middle-aged female dressmaker.

Clara’s mother had been a school teacher in West Bloomfield in her youth, and it seems Clara was pursuing the same life. From modest farm means, Clara had lived a very different life from her roommate, the daughter of an established Harvard Physician. Clara would have likely been known as a “dig” by her peers, the late-19th collegiate term for a modest, scholarly student attending Smith more as a means as a career than as a past-time before marriage.

We don’t know how close Laura and Clara were, but it is obvious they enjoyed one another. Neither asked to move rooms for the entirety of Laura’s time at Smith (which occurred, to much drama), and despite the class difference, relationships between roommates could and did flourish. Josephine “Jo” Wilkins, a student on full scholarship who lived in Wallace House the year after Laura’s death (and incidentally, lived in Laura and Clara’s old room), boarded with Constance Perley Wilder—a millionaire. In her letters home, Jo relates how she would darn Constance’s socks for spare change, writing light-heartedly of the heiress’ ditsy ways. Despite this large class barrier (and we cannot deny the hardship behind her letters), Jo relates how Constance paid for all of their furniture and decorations, and how happy they were at the arrangement.

Money still dictated much of the lives of Smith students. Jo writes of girls whose fathers had gone bankrupt, and how they were forced in shame to move out of Smith housing and into inferior boarding houses downtown. Much of the social culture at Smith depended on access to disposable cash in one way or another, such as being able to host small eating parties (“spreads”) or simply call a carriage for a day trip. Poorer students had no social shield for their richer peer’s elaborate new dresses or gifts from home, nor could they simply attend a casual dance if they had not learned the moves somewhere in childhood.

A level of democracy was held through the leadership of the Housemother though. The woman chosen to reside as Wallace House’s first Housemother was the recently widowed Mrs. Sarah Robinson. Fifty years old and a survivor of the Great Chicago Fire, Mrs. Robinson moved from Boston to Northampton at the bequest of the school for the fall term of 1889. She lived on the first floor across from the dining room, and student photographs of her open room show the intimate relationship she held with her students. As Housemother, Mrs. Robinson was in charge of her students’ social lives, the finances of the house, and the general well-being of the young women. Diaries and letters attest to her loving but motherly ways, unafraid to tell her girls off for disorderly behavior.

The young English professor Marie Elizabeth Josephine Czarnomska (pronounced “Chanmpska”) was chosen to live in Wallace House as the resident faculty member. Known (perhaps) affectionately as “Chumpy” by her students, Miss Czarnomska could be an iron lady. She was rumored to be the daughter of a Polish aristocrat who had fallen on hard times and was often called “the Czar” for this double temperament. Her American mother had died in her childbirth and she was raised with the New York intellectual elite. Even after she left Smith to become a Dean of Women at the University of Cincinnati, Miss Czarnomska cherished her time at Smith and kept a book of her past student’s achievements. Towards the end of her life, former Smithies contributed a memory book for her, a cherished item she kept next to her Bible and prayerbook.

The dining room etiquette was strict. The girls were no longer living at home and now had to adapt to the pressures of living in a “proper” school environment. Each girl had her own assigned seat and had to attend each meal unless she had permission to be excused. It was not unheard of for Mrs. Robinson or Miss Czarnomska to read poetry during these meals, as they did after dinner in the parlor before bed.

One student in Wallace House wrote home to her mother only a year after Laura’s death about the new living arrangement, and how different it was from the simple boarding house she lived in off-campus:

The dining room etiquette is very formal. As soon as the bell rings, the girls go to their places, standing behind their chairs till Mrs. Robinson takes her seat, when we all do. Then as soon as all are seated, Mrs. R. taps a bell, & all bow their heads for a silent grace.

At breakfast, each girl may ask to be excused when she wishes, at dinner, we go by tables, but at supper we must wait till all are ready & Mrs. R. rises. It is her hobby to have the dining room quiet.

She thinks there is no attraction in a young girl as a low, sweet voice, & tries her best to make her girls cultivate such voices. I don’t really see how a girl whose has a naturally high voice is going to reduce its pitch, but of course she can put less volume into it.

One of the waitresses (and maids who lived on the top floor) was a young woman named Delia. She was well liked, and often aided and abetted the students in her house with their mischief. One story reveals how she wore an identical bright yellow necktie to Miss Czarnomska, standing behind the professor and smirking at her students for the ridiculousness of the accessory. It was too dangerous a game though, and Delia left before she or the Wallace house girls could crack and all would face her wrath. She would later that year help them lie to Mrs. Robinson about a Mountain Day firework prank that got out of control. Delia was certainly admired.

In all ways, Laura was a normal Smith College student.

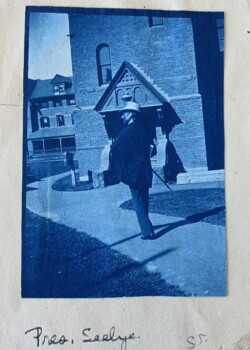

She attended a chapel service every morning led by President Seeyle, made her way to Bible class with him, did her best at Elocution under the tutelage of Miss Ludella Peck—a woman known for her somewhat-frumpy appearance. This was quickly ameliorated by the presence of Miss Mary A. Jordan though, the Rhetoric professor was somehow the same age as Miss Peck but twice as well dressed.

Miss Jordan, or “Jordie” as her students called her, was the most popular and vivacious professor on campus. An 1876 graduate from Vassar College, Mary soon acquired her Master’s in English and was led quickly to Smith by the personal request of President Seeyle. Keeping her private room in Hatfield House always open as a library or tea spot, Miss Jordan was particularly involved in her student’s well-being, counseling anxieties or aiding in classwork. Student plays lightly mocked her striped gingham petticoats and yellow handkerchiefs she wore on rainy days, but her presence was deeply loved. At the 40th anniversary of her teaching, a large bound book was presented to her of memories from past students, with one summarizing the flame quite well:

Brisk entry into the classroom; her quick settling in her chair; the petite figure in the dark, tailored suit, with a hair-line stripe and silk braid finish; the little ivory skull swinging from a gold pin above her watch pocket; the inscrutable face, with flashing eyes framed in a dark pompadour––an owl’s face. . . she seemed as wise as the Sphinx and as firmly based as the great Pyramid; she knew everything and she told me she had learned Sanskrit while waiting for the Hatfield House girls to come down for breakfast. . . she inculcated freedom of action.

Despite being wrapped up under Miss Jordan’s charms, Laura was able to pass Mathematics well with Miss. Eleanor P. Cushing, as did one of her favorite subjects, Ancient Greek with Professor Henry M. Tyler. Latin could not go by faster, and she thanked God above she had only a year of it with the “Southern Gentleman” Professor John Everett Brady. The last, and most welcome of her classes was Hygiene, taught by the resident Physician Dr. Grace Preston.

By her second year, Laura had added Chemistry and French, happily dropping Latin nearly for good (she still had a trimester to slog through at the end of the year). Her grades had been near failing in it, and she was happy to devote her time to pursuits she was much more suited for. Laura stayed on with, Elocution, Greek, History, and of course Rhetoric—doing only one more trimester of Math.

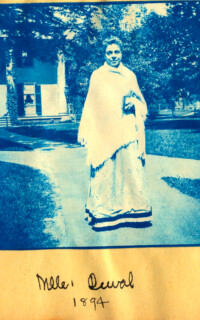

French was Laura’s best subject. She received the highest marks possible in the subject, even taking an extra hour of it her last trimester of the year. French was taught by Mlle. Delphine Duval, a new professor who only began her placement a year previously. Left an extreme orphan early in life, Delphine had no next of kin and it is unknown where or how she made her way to the United States. After teaching French through schools in the country, at the age of 51 had taken the position at Smith College. Like Laura’s oldest sister, Mlle. Duval was a skilled miniature painter, as well as a noted musician and embroiderer.

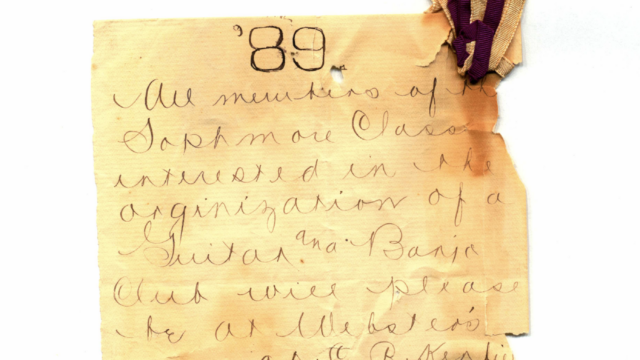

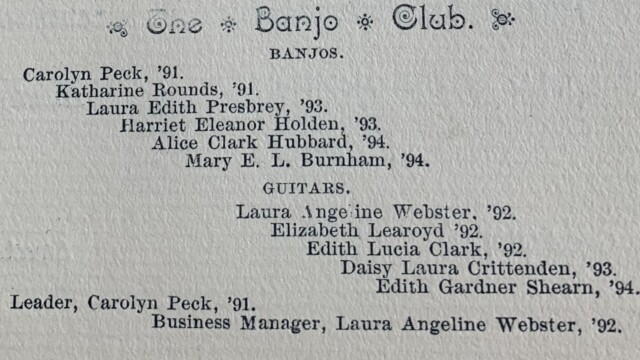

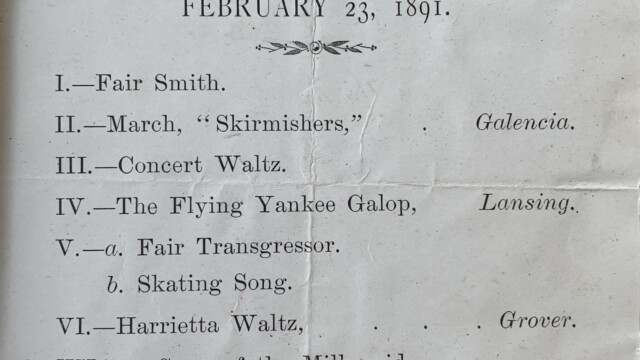

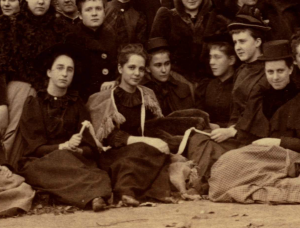

Laura was like other students. She went to dances, lectures, concerts and plays—but it seems she spent much of her free time with friends playing the Banjo. Laura had been playing the instrument for some time now, as not only did she join the Smith College Banjo Club as soon as she arrived, but photos attest to the white drum’s wear. Playing shows once or twice a year for her classmates, Laura stayed on in the club until her death. Numerous photos were donated by Florrie in 1940, and it is singlehandedly the largest trove of Laura’s life that we know.

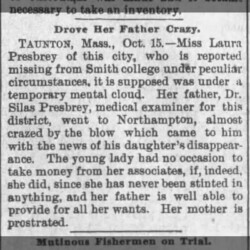

The years passed, and soon Laura began her Junior year. Her mind had bothered her recently, anxious ticks and moments of madness she could not control. She couldn’t seem to sleep either, bothering Mrs. Robinson and then Dr. Preston for sleeping powders.

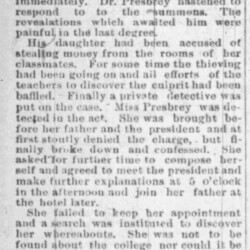

Something was possessing her. She could not stop stealing—money, trinkets, foods—No matter how horrible it felt after, the rush and utter need of the act consumed her. It was too easy! Pocketbooks left on the parlor fireplace, purses invariable stuffed in coats! She knew people were talking, beginning to wonder where the little cash they were sent home went, but what could she do? It was too shameful. Page after page in her diary she detailed her anguish. She could not focus on her studies to save her life. The usual night talks with Clara began to be strained. She was truly going mad.

Sometime on Saturday or Sunday, Laura snuck into a janitor’s bedroom. She began to search through his things for his pocketbook when he opened the door. Laura turned by instinct. She stilled in terror.

She had been caught.

That night she was called into President Seeyle’s office. He confronted her with the situation at hand, and like a deck of cards, the young woman folded. Sobbing, Laura admitted her goal—to find money. It had been her who had taken the missing purses, and she had no idea why! Her shame was white-hot and unending.

Seelye saw the grief and guilt carved into her whole body. “I will not tell anyone,” he promised, “but I must tell your father.”

Laura nodded. “I would like that,” she admitted. She loved and trusted her father, and wished to tell him everything. Maybe he could cure her of whatever was occurring in her head.

“He will forgive you,” Seeyle promised. “I will speak to him.” Laura nodded again and he sent the student out. He ordered a telegram to Dr. Presbrey immediately, asking him to come as soon as possible to the college.

He would end up having a very different conversation with Silas than he had prepared for.

Monday morning Laura sat, attempting to eat. It was noon. Nothing tasted right. She could not be excused, and she avoided all eye contact with her tablemates.

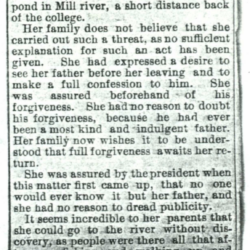

Laura could see Mrs. Robinson come nearer, and she knew before it was out of the old woman’s mouth what was to happen: her father was truly coming. Dread paralyzed her. She got up and climbed the stairs to her room one last time. She was wearing her favorite dark blue dress, preparing for the chilling air with her bright red coat and blue cape. Laura wrote a letter to her father and then once more in her diary her plans for “Paradise”. The terse entry is the only words we have directly from her:

I have just done a dreadful thing, it is too horrible to write of here, and why I did it I do not know. I have brought disgrace upon myself and cannot survive it; I shall drown myself in “Paradise”; do not search for my body.

Laura left the Wallace.

No hat. There was no need for that anymore.

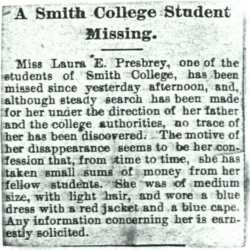

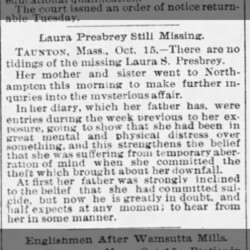

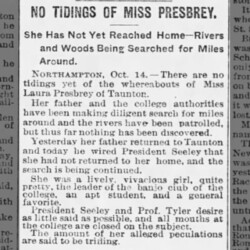

The day had started like any other—except for Professor Gardiner—who overslept and missed his morning Psychology class. While the girl’s laughed and wrote home of the free hour, the rain beat terribly. Word was beginning to spread of Laura’s disappearance, but at this time only the faculty knew, and the Wallace House students who did know were strictly forbidden to speak of it. By Tuesday evening a small newspaper notice had been published about her whereabouts, but by Wednesday the secret was out.

Winifred Ayres was a Hatfield House student one year older than Laura. Writing in over four volumes about her time at Smith College, Ayres recounts the trauma of the campus firsthand. The Wednesday morning after Laura was last seen, Ayres relates how the news was broken to her.

Anna came over before chapel and told us about Laura Presbrey’s disappearance—a terrible thing; her friends are so depressed and almost prostrated.

The tense gossip continued as the girls walked to College Hall for the morning sermon. The girls of Wallace House could see their friends from other houses staring.

The news weighed heavily on President Seelye. He remembered the scared girl in his office. Was this his fault? He knew he had to address the disappearance to his students. At chapel that morning he read the parable of the Prodigal Son, leading his young worshipers in the hymn “A Love Divine” before preaching on the bounty of forgiveness.

On Thursday, Seelye read the entirety of Isaiah 55, leading his students once more with the hymn “There’s a Wideness in God’s Mercy.”

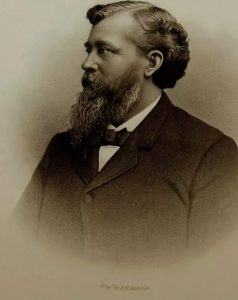

Dr. Silas Presbrey had arrived Monday evening at the behest of President Seeyle. What he did not anticipate was his daughter being missing.

Seeyle’s office was crowded—and loud. The president had been silently whisked away from his Bible class at Mrs. Robinson’s horrific discovery. Laura had not made it to supper, and the Diary seemed to explain why.

Everything had changed in that hour. Silas was yelling, demanding an explanation. How could a girl go missing in broad daylight? Seeyle could not hold him back. Janitors watched on. Mrs. Robinson sat prostrated, attempting to answer questions no one knew. She handed the diary to Laura’s father, and they took turns reading together, attempting to trace the girl’s steps anywhere else than the bottom of Paradise Pond.

“We must tell the truth,” Silas told the group. “Don’t hide this any longer, and don’t let rumors grow.” Seelye notified the presses. But it was fruitless. Dr. Presbrey had to leave soon. He had patients back home. He sent a telegram to his friend and Taunton Gazette Editor William F. Greenough to replace him in the search.

By Wednesday, Florrie and her aunt had come to help in the search, but they could do little in the face of such anxiety. The faculty and students Florrie had known and loved already believed her sister dead, and it was unbearable. By Friday noon the two had said goodbye to Mr. Greenough and left on a train back to Taunton.

Two hours later, the worst had come true. Northampton police officer Mr. Gilbert and Smith janitor as Frank King were on the water searching once again when family-friend William Greenough saw blonde hair. “It’s her hair,” he told the two, “we’ve found her.”

William had previously investigated around town, going to Mt. Tom and the surrounding train stations to see if anyone had seen her. Turning over a broken tree trunk, the grappling hooks uncovered Laura’s body. It floated up like a rag doll. At exactly 2:45 pm, William pulled the girl’s sopping body up onto the boat by her collar. He cried out, unable to understand the death between his hands. He had known her since birth. How? Why?

She was still in her dark blue dress and cape. Taunton would forever be changed.

Word traveled fast. Was it from students on the Pond bank, watching their classmate’s dead body be brought back to land? Was it from Mr. Greenough’s cries, or simply a message from Seelye? No matter how it was related, Winifred Ayres wrote home of the horrific news.

This afternoon news came that they had found Miss Presbrey’s body in Paradise Pond—poor girl, and her poor distracted friends! This evening May and I went over to see Anna; the Wallace House seems like a tomb. After I came back I “observed” for an hour and a half out of my window, and nearly broke my neck.

The next morning was haunting.

There is the most awful gloom over the College. Still recitations go on as usual and her best friends attend them. I suppose it really is better, although it seems heartless.

Jo Wilkinson wrote her mother of the tragedy, picking up gossip that hadn’t even hit newspapers.

It is now known that she did not confess of her own accord, but that the janitor caught her in his room, and told the president and on his interviewing her she confessed that she had taken things. In her diary she wrote that she had done a dreadful thing, too horrible to write, and later that she should drown herself in Paradise. Of course it has colored everything which has happened in college this week. Many believe that she was insane, and again, many do not.

There may be some truth to the idea that mental illnesses ran in the family. In the 1920 census, Laura’s older sister Clara is listed as residing in the Butler Hospital for the Insane. The reason for her stay at the Rhode Island hospital is most likely hidden away in a record book at Harvard, but it is obvious something must have been serious enough for her prolonged stay.

Laura’s sister and aunt seemed resigned to the fact as well at the time. Upon either searching their home or receiving a letter from Laura herself at some point soon before her disappearance, the two reported that there was indeed evidence she had not been in her right mind at the time of her death.

By Sunday night, the entire school crowded into Vespers service to hear President Seeyle’s words. The students needed him. “He is simply fine, under all circumstances,” Jo wrote home. “Everyone just loves him”. Seelye read Matthew 18 passionately, remarking on the enormity of sin—but also God’s infinite love and forgiveness.

His wife Henrietta noted her husband’s ailing health. Nothing in the history of the college had so affected the president. She prayed he would recover quickly.

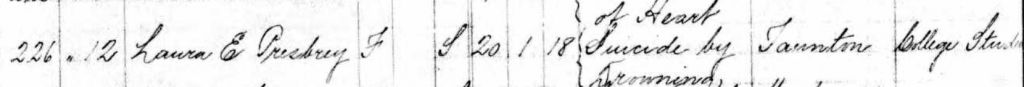

But what of Laura? After her body was found it went to the local undertaker for a routine autopsy. It was more of a formality than anything.

It was 10:50 pm and Mr. William F. Greenough sat alone in the train compartment. He watched as his train moved out of Northampton’s station, its long journey ahead somehow a welcome calm. He couldn’t understand how the cold body of such a warm girl was in the compartment behind him.

It would be a very long night.