by Alexi Bonenfant

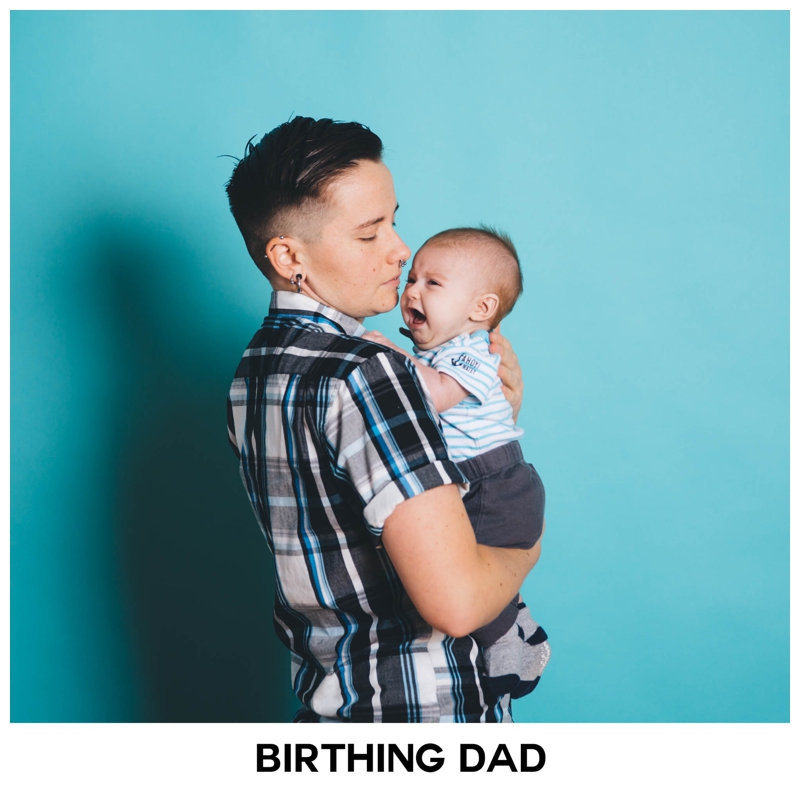

In this podcast, we will dive into the relationships of the often overlooked bridge between trans health with the founding concepts of reproductive justice, specifically bodily autonomy. In the unsure future women and other trans individuals face while looking towards another Trump presidency, we look to the past and ask what should we do?

Transcript

In recent years, especially since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the question has risen of what rights are truly protected for Americans. When we lost Roe, we lost the outlined right to bodily autonomy. What could go next? With the recent re-election of Donald Trump, all bets are off. We, as a community, must come together to protect our rights, with many of them being threatened daily by MAGA supporters and soon-to-be officials (if they aren’t already in office). So, today I’ll be discussing what Trans rights and Reproductive Justice activists will have shared concern for going into the next four years and beyond as well as, more importantly, how we can combat it. My name is Alexi Bonenfant and this is Autonomy: A Trans’/Women’s Rights Issue in Trump’s America.

The overlap in Trans and Reproductive Justice is not a new confounding idea. There is a long trail of overlapping concepts, goals, and efforts to better meet the needs of the people these movements support. As Marie-Amélie George brings up in her work, R.J. and Trans Rights activists are often fighting in support of the same founding principles, which she lists as “dignity, autonomy, privacy, liberty, and equality.” Both sides, though the lack of these rights have developed into different end-goals for their respective movements based on circumstance and external beliefs, are based on the same reasoning. They want to be able to do what they need to for their health, whether it be physical or mental. The right to choose–may it be the option to refuse birth control or to get surgery without going through hormone therapy–is exactly that. Doing what is best for you. The individual.

As Loretta J. Ross says in her work, “Reproductive justice thrives in the borderlands of ambiguity, and its incompleteness offers amazing flexibility and adaptability to allow multiple interpretations that invite elaboration and clarification. Reproductive justice is a process of synthesis with which to explore new territory and make new human rights claims.” It is suited for the different but similar needs of many, being built in a time where Black feminists “created the conceptual space for focusing on the experiences of Black women as a fertile site for creating new theory and activism based on shared—but not identical—stories of reproductive oppression.” The sense of unity is necessary for the movement, but the emphasis on individual experience ties it back to the fact that not everyone can be benefited if we form too tight of a mold, too tight a list of demands. This also resonates in the Trans community, as there is no one way to be trans. Even outside of the borders of, for example, trans-men and women or trans-masculine and feminine people, the trans community is too diverse to pocket into one outline. There are too many identities, even those that completely oppose one another, and too many ways one may choose to express themselves to create an outline of what “trans” is and what trans people need. Again, not all trans people choose to undergo treatment like hormonal therapy, top surgery, bottom surgery, or any other medical gender-affirming care. They may choose some, all, or none at all. To confine a group defined by its acknowledgement that gender is flexible and then put it into a list of requirements, like many medical professionals have historically done and still continue to do, would dismantle the founding principles of the movement. “[D]ignity, autonomy, privacy, liberty, and equality.” There is nothing liberating about being forced into a body you don’t want because it was what was expected of you via what you were born with or transitioned into. There is no autonomy if other people corner you into an identity. These two groups are based in their flexibility: which makes them equally compelling to those in need as they are threatening to those who wish to eliminate these movements.

Which brings us to today. The man who, as Michel Martin and Mansee Khurana remind us, chooses to put messages like “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you” at the end of his advertisements, has built a large following specifically for his platforms built on “pro-life” and anti-LGBTQ+ beliefs. With the House and Senate controlled by the Republican party, almost the same supreme court that overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, a few (to understate) particularly shocking appointments expected to be made when Trump enters office, and a very detailed (and horrific) outline in Project 2025 of what some far-right conservatives plan to do in this upcoming term, things don’t sound too great. So, in a world where we are less than two months away from another Trump presidency, what do we do? We now know what it is we need to fight for. The mutual belief in these fundamental rights gives us that. But how do we fight? For this, I look to the history of both movements. The push here is unity, so what better way than to share the paths taken to achieve improvement before. In fact, unity is one of the core strings that remains present throughout activism–there’s power in numbers, so to speak. Throughout Susan Stryker’s article, a history of “Transgender Activism,” we see peer groups forming to develop community support–yet again, shared but different experiences. Being able to know you are not alone can help lift part of the emotional burden of the individual, but can expand into action. As Ross discusses, second wave feminists, for example, went for legal protections, demanding that laws be put in place to protect their reproductive choices. They worked to build from the ground up, trying to protect those who could not afford abortion even if it had been legalized, as well as the R.J. movement specifically working to protect Black women in their fight for bodily autonomy as a group at the intersection of oppression and inequity of both sex and race. They came together and fought not only the common causes, but the expansive needs of all. Trans groups did this as well, as Stryker points out, forming“correspondence network[s]” and “dragg[ing] transgender issues to the forefront of San Francisco’s queer community, and at the local level successfully integrat[ing] transgender concerns with the political agendas of lesbian, gay, and bisexual activists to forge a truly inclusive glbtq community.” Coming together, unifying, and fighting for one another have been used before successfully–so why not now?

With every push forward for one community, another community steps back, therefore the push back from privileged communities following the rapid progress of marginalized communities in America came as no shock to those aware of this historical pattern. So when we look for what changes we can make living in the twenty-first century, joining together these similarly rooted movements must be contemplated. The merging of these can only benefit us, giving us both power in numbers as well as varying experiences needed to gain more traction in our efforts to enact social change. Though smaller groups based in more similarities are a resource that should in no means be dismantled as they provide safety, comfort, and power, we must think about what unity, tried and true, can bring us in these four years and beyond.

Resources

Alper, Barbara. [My Mind My Body My Freedom]. n.d., photograph, The New Yorker, n.p., June 23, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/books/double-take/sunday-reading-the-challenge-to-reproductive-rights-in-america.

Couceiro, Cristiana. [Keep Your Laws Off My Body]. n.d., illustration, The New Yorker, n.p., June 23, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/books/double-take/sunday-reading-the-challenge-to-reproductive-rights-in-america.

George, Marie-Amélie. “Queering Reproductive Justice.” University of Richmond Law Review 54, no. 1 (2019): 671-703 https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/urich54&id=694&collection=journals&index=

Koyama, Emi. “The Transfeminist Manifesto.” In Catching A Wave: reclaiming feminism for the 21st Century, edited by Rory Dicker and Alison Piepmeier. Northeastern University Press, 2003.

Martin, Michel and Mansee Khurana. “What Trump’s win could mean for transgender health care access, athletes.” NPR, November 16, 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/11/15/nx-s1-5181967/what-trumps-reelection-could-mean-for-transgender-health-care-access.

Nixon, Laura. “The Right to (Trans) Parent: a Reproductive Justice Approach to Reproductive Rights, Fertility, and Family-building Issues Facing Transgender People.” William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law 20, no. 1 (2013): 73-103 https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/wmjwl20&id=86&collection=journals&index=

Pollauf, Colette. Participants at the Transgender Day of Visibility rally march through the Boston Common, holding signs and chanting. n.d., photograph, The Boston Scope, n.p., April 4, 2022. https://thescopeboston.org/7868/news-and-features/news/trans-rights-advocates-march-for-transgender-day-of-visibility/

Ross, Loretta J. 2017. “Reproductive Justice as Intersectional Feminist Activism.” Souls 19, no. 3 (2017): 286–314. doi:10.1080/10999949.2017.1389634.

Stryker, Susan. “Transgender Activism.” glbtq, n.d. http://www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/transgender_activism_S.pdf

—

Stock Music provided by soundmake, from Pond5