by Sofi Maranda

Reproductive Justice Futurism, as introduced to our class by Loretta Ross, is a blending of Afrofuturism and Reproductive Justice – a theory and perspective that questions how scientific and technological advances may play into neoliberal and white supremacist ideas of who is disposable and who is worthy of reproduction. “Futurism,” however, raises the question – why is this relevant now? What does thinking about the future have to offer us in the present moment? With the unfortunate circumstances of the recent election, however, the future doesn’t seem that far away. This podcast seeks to explore how science fiction and imagination through an RJF lens can allow us to interrogate the threats techno-utopianism and techno-futurism pose to our reproductive rights, as well as offer a medium to begin dreaming up a more just future.

Transcript

Reproductive Justice Futurism, as defined and theorized by activist and Smith College professor Loretta Ross, is a blending of the theoretical concepts of Afrofuturism and Reproductive Justice.1 Afrofuturism was coined in 1993 by author Mark Dery and, according to Afrofuturist scholar Ytasha Womack, “is a way of looking at the future and alternate realities through a Black cultural lens.”2 This includes creative work, which often means science fiction but also includes visual arts, music, and dance, that allow Black people to imagine themselves in the future – as a form of self-liberation and self-healing, as Womack explains.3 In their TEDx performance, “An Afrofuturist Birthed Me,” poets Ajanaé Dawkins and Tasha Lomo declare, “What do you know about black people in the future? Here is what I need you to know black people we do survive. By magic or manual by spirit or our own fly technology, we do make it to the future.”4

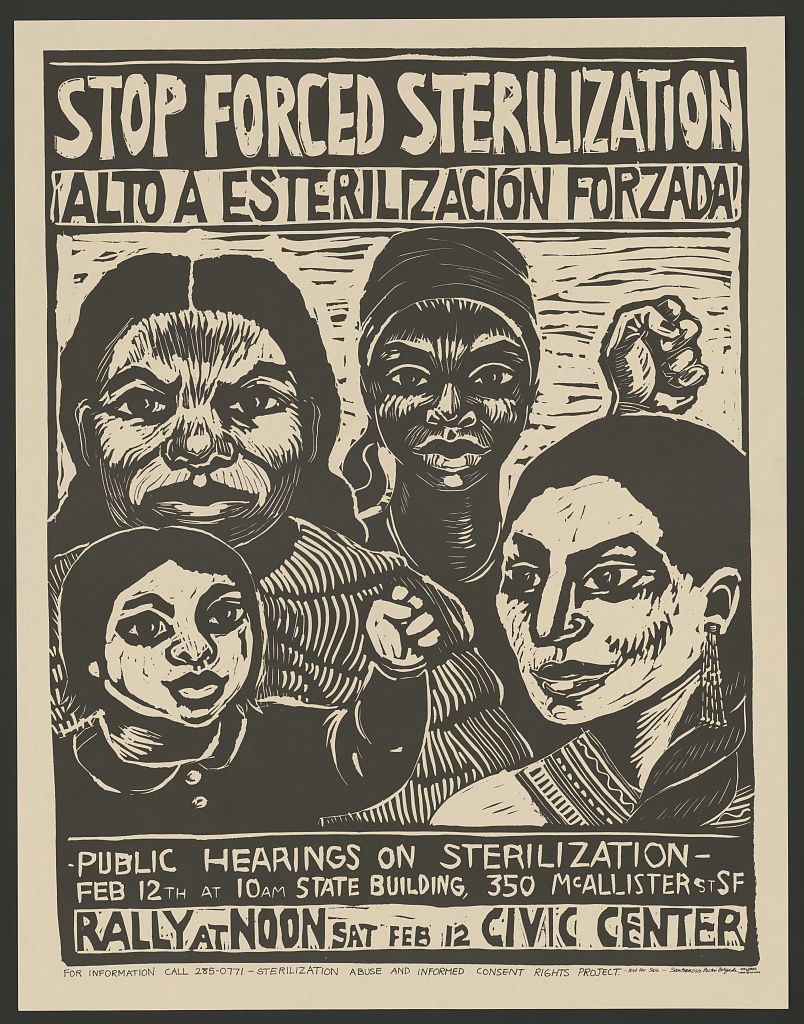

Reproductive Justice, defined by the SisterSong Collective, is a goal and a framework that declares “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”5 RJ, according to Ross, intersects with Afrofuturism in an interrogation of techno-utopianism and resistance of techno-eugenics through the lens of Black women’s reproductive experiences.6 Reproductive Justice Futurism, or RJF, lives at this intersection. RJF questions how scientific and technological advances such as Assisted Reproductive Technology (or ART), defined by the CDC as all fertility treatments that handle either eggs or embryos, perpetuate the power disparities that enable harm and injustices against Black bodies.7

RJF examines how technologies like ARTs and other aspects of what Ross refers to as “over-hyped futurism” lean into white supremacist and neo-liberal ideation of who is worthy of reproduction – as well as who is worthy of making decisions about reproduction – and who is not. This can also be framed as, who gets to create a family, and how? We see this now in debates over what types of families get to have children, and who gets to decide when someone can have children. Eugenicist models have reappeared in new and old forms throughout history, currently visible in restrictions to family planning and reproductive healthcare, and on the horizon as gene selection becomes more and more feasible. Turning back to Dawkins and Lomo’s poem, who will be there in the future? Who will be deemed unworthy of entering the future?

Black feminist activists and theorists have been talking about children and the future of bodily autonomy for a long time, even before there was terminology around Reproductive Justice. Imagination has played a core part in this, from imagining freedom from enslavement to deliverance from systems of racism and white supremacy. For example, Audre Lorde said in her keynote address at the First National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gay Men in 1979, “We are here because each of us believes in a future for ourselves and for those who come after us. We are redefining our power for a reason, and that reason is a future, and that future lies in our children and our young people. I’m speaking here not only about those children we may have mothered and fathered ourselves, but about all our children together, for they are our joint responsibility and our joint hope. They have a right to grow, free from the diseases of racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and the terror of any difference.”8 These same sentiments are echoed in the understanding of Reproductive Justice built by a group of visionary Black women in 1994, including Loretta Ross, who went on to create the SisterSong Collective.9 As Lorde repeats over and over, the reason for coming together, the reason for taking action, the reason to keep working is a future. A future, one to imagine and believe in – one for the children. This, too, is Reproductive Justice Futurism, advocating for a future in which children, as a collective, are able to live and grow free from the systems of oppression that have harmed and continue to harm Black people throughout history. Lorde names these systems, and declares the human right to be free of them – and believes that there will be such a future in which this is true.

But what about “futurism” is relevant to our present moment? What does thinking about the future have to offer us, on the brink of a second Trump presidency, as technology advances exponentially and the Earth rapidly approaches the point of no return? Suddenly, the “future” doesn’t seem that far away, and it’s getting hard to imagine things getting better. But Reproductive Justice Futurism is where we can find these answers, where we can question the options we’re offered, and begin to imagine a better world, for ourselves and for our children. In an American Studies Association conversation on Reproductive Futurisms between Loretta Ross and Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Ross reminds us, “I am not one of those that imagine, in a reproductive futurist conversation, that we’re going to be post-white supremacy. I actually think white supremacy will take advantage of all the technological advancements to re-inscribe itself and so we need to anticipate that.”10 She continues, “We need to prepare [for] and anticipate eugenics. I think it is naive to hope that it will go away.”11 As Ross states, imagination does not need to wait until a mystery point in time when issues such as white supremacy have been overcome, in whatever capacity that might entail. Futurism starts now, interrogation and imagination start now. The threat of eugenics looms over concerns of how the Trump administration will handle the development of reproductive technologies – as well as how they will decide who is worthy of access to such technologies and, in turn, who is worthy of reproduction. And these are real and frightening worries.

So how do we imagine futures and move forward with RJF in mind? This is where science fiction – science fiction intersects both Afrofuturist and feminist narratives – comes into play. Science fiction has long theorized about technological advances that deal with gestation and reproduction. For example, the 1997 film Gattaca’s portrayal of artificial wombs offered a glimpse of how eugenics could infiltrate reproduction through “screening” embryos for traits outside of the approved selection.12 Beyond reflecting anxieties of what the future of reproductive technology holds, however, much of mainstream sci-fi perpetuates harmful views of reproduction and who can reproduce. This is why, when considering the future through an RJF lens, science fiction must be rooted in this intersection of Afrofuturism and feminism. In her piece, “Reproductive Justice: The Final (Feminist) Frontier,” Zoe Tongue, lecturer at the University of Leeds, writes, “Within feminist science fiction narratives, it becomes possible to critique our current gendered, racialized, and class-based structures and imagine alternative futures. The genre provides an avenue for reconceptualizing what our society and its structures and institutions, including law, should—or could—look like, providing the opportunity for a radical rethinking of how reproduction takes place.”13 Science fiction offers a medium for imagining a future beyond the boundaries of current discourse – which can then be used to restructure our current systems so we can build these futures. Prominent Black feminist sci-fi writers such as Octavia Butler engage in this world-building and imagining, but also, as Tongue discusses, portray “reproductive injustice deliberately, with a fictional or future society failing on those four tenets [of RJ] to highlight how those failures are or have historically been present in our society.”14 This kind of engagement is conscious of both current and historical reproductive oppression and offers another way to interrogate the ways in which techno-eugenics overlay ideas of the future.

Imagining, however, goes beyond engaging with and creating sci-fi. In her blog post, “afrofuturism and #blackspring,” writer and activist adrienne maree brown writes, “what we are all up to, this changing the world willfully, is science fictional behavior. because all organizing is science fiction. we are creating a world we have never seen. we are whispering it to each other cuddled in the dark, and we are screaming it at people who are so scared of it that they dress themselves in war regalia to turn and face us.”15 She continues, “science fiction is not fluffy stuff. afrofuturism is not just the coolest look that ever existed. the future is not an escapist place to occupy. all of it is the inevitable result of what we do today, and the more we take it in our hands, imagine it as a place of justice and pleasure, the more the future knows we want it, and that we aren’t letting go.”16

So. While we’re scared, while we’re uncertain: our imaginations are our strongest tool. We will be in the future, so what do we want that to look like?

- Lorretta Ross, “Reproductive Futurism” (presentation, SWG 150, Smith College, Northampton, MA, October 10, 2024). ↩︎

- “Afrofuturism,” LibGuides, Pratt Institute Libraries, last modified August 27, 2024, https://libguides.pratt.edu/afrofuturism; Ytasha Womack, “Afrofuturism Imagination and Humanity,” Sonic Acts Festival: The Noise of Being, De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, February 26, 2017, 25 min., 10 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlF90sXVfKk&t=13s. ↩︎

- Womack, “Afrofuturism Imagination and Humanity.” ↩︎

- Ajanaé Dawkins and Tasha Lomo, “An Afrofuturist Birthed Me,” TEDx, Columbus, Ohio, US, December 13, 2023, 9 min., 22 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kjjP818nU8. ↩︎

- “Reproductive Justice,” SisterSong Collective, last accessed November 24, 2024, https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice. ↩︎

- Ross, “Reproductive Futurism.” ↩︎

- “Assistive Reproductive Technology (ART),” CDC, last reviewed October 8, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/art/whatis.html; Ross, “Reproductive Futurism.” ↩︎

- Audre Lorde, “‘When Will the Ignorance End?’ Keynote Speech at National Conference of 3rd World Lesbians & Gay Men,” Off Our Backs 9, no. 10 (1979): 8–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25793146. ↩︎

- SisterSong Collective, “Reproductive Justice.” ↩︎

- Loretta Ross, “Reproductive Futurisms: A Conversation w/ Loretta Ross and Alexis Pauline Gumbs,” moderated by Jina Kim, virtual conversation, June 17, 2020, ASA Freedom Course, YouTube, 54 min., 57 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-WPC0-qigE. ↩︎

- Ross, “Reproductive Futurisms: A Conversation w/ Loretta Ross and Alexis Pauline Gumbs.” ↩︎

- Grace Kim, “Gattaca (1997),” Embryo Project Encyclopedia, ASU, February 9, 2017, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/gattaca-1997. ↩︎

- Zoe Tongue, “Reproductive Justice: The Final (Feminist) Frontier,” Law, Technology and Humans 4, no. 2 (2022):101, https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.2468. ↩︎

- Tongue, “Reproductive Justice: The Final (Feminist) Frontier,” 102. ↩︎

- adrienne maree brown, “afrofuturism and #blackspring (new school, #afroturismtns,” blog post, May 2, 2015, https://adriennemareebrown.net/2015/05/02/afrofuturism-and-blackspring-new-school-afroturismtns/. ↩︎

- brown, “afrofuturism and #blackspring (new school, #afroturismtns).” ↩︎

References

brown, adrienne maree. “afrofuturism and #blackspring (new school, #afroturismtns).” Blog post. May 2, 2015. https://adriennemareebrown.net/2015/05/02/afrofuturism-and-blackspring-new-school-afroturismtns/.

CDC. “Assistive Reproductive Technology (ART).” Last reviewed October 8, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/art/whatis.html

Cuaron, Mita. “Nacimiento.” 2004. Print. Self Help Graphics and Art. https://www.selfhelpgraphics.com/blog/agency-accessibility-and-abolition-exploring-reproductive-justice-in-art.

Dawkins, Ajanaé and Tasha Lomo. “An Afrofuturist Birthed Me.” TEDx, Columbus, Ohio, US, December 13, 2023. Video, 9 min., 22 sec, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kjjP818nU8.

Gaskins, Nettrice. “Who Fears.” 2021. Digital art. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Who_Fears_2021.jpg.

Kim, Grace. “Gattaca (1997).” Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Published by Arizona State University, February 9, 2017. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/gattaca-1997

Lorde, Audre. “‘When Will the Ignorance End?’ Keynote Speech at National Conference of 3rd World Lesbians & Gay Men.” Off Our Backs 9, no. 10 (1979): 8–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25793146.

Palencar, John Jude. “Parable of the Sower.” 1995. Cover art. The Thinking Man’s Idiot (Charles Lewis III). https://thethinkingmansidiot.wordpress.com/2014/03/18/crab-barrel/parable-of-the-sower/.

Pratt Institute Libraries. “Afrofuturism.” Last modified August 27, 2024. https://libguides.pratt.edu/afrofuturism.

Robinson, Stacey and John Jennings. “First Kontakt.” 2013. Digital Art. Black Kirby Presents: In Search of the Motherboxx Connection: Exhibition Catalog, 43. MET Museum Archive. https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/library-afrofuturism.

Ross, Loretta. “Reproductive Futurism.” Presentation for SWG 150 class at Smith College, Northampton, MA, October 10, 2024.

Ross, Loretta. “Reproductive Futurisms: A Conversation w/ Loretta Ross and Alexis Pauline Gumbs.” Moderated by Jina Kim. Virtual conversation, June 17, 2020. ASA Freedom Course. YouTube, 54 min., 57 sec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-WPC0-qigE.

SisterSong Collective. “Reproductive Justice.” Accessed November 24, 2024. https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice.

Tongue, Zoe. “Reproductive Justice: The Final (Feminist) Frontier.” Law, Technology and Humans 4, no. 2 (2022):95-108. https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.2468.

Womack, Ytasha. “Afrofuturism Imagination and Humanity.” Sonic Acts Festival: The Noise of Being, De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, February 26, 2017. Video, 25 min., 10 sec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlF90sXVfKk&t=13s.