by Etta Singer

From the Virgin Mary’s to a lesbian safe haven, how did we get here? When, why, and how did Smith become the queer hotbed we know today? This podcast explores a small part of Smith’s queer history, centering around interactions between the school’s administration and lesbian student’s in the early 1980s.

Transcript

In 2024, Smith College is a hub for the LGBTQ community. From students all the way up to administrators, queer individuals play integral parts in all of college life. In my few months at the school, I’ve heard far more classmates come out as straight or cisgender than any queer identities, because, in many ways, queerness has become an unspoken default in the Smith community. But I was curious, has Smith always been this way? The short answer is no. Smith was once an institution for New England’s rich, white, straight-laced young women that was proudly represented by our original mascot: The Virgin Marys. But then I asked when, why, and how Smith became the safe haven of sapphic joy I know today. Hi, I’m Etta Singer and this is “The Rise of Lesbianism at Women’s Colleges: SCLA In the 1980s,” a podcast episode exploring one small part of Smith’s rich queer history. This study is meant to illuminate important issues relating to the fourth pillar of Reproductive Justice, that focuses on bodily autonomy, sexual pleasure, and liberation.

~ ~ ~

My first question of “when?” was the easiest to answer. I came across many interesting documents, in the forms of letters and journals, proving there have always been queer students on campus, but Smith’s lesbians truly became a vocal group in the early 1980s. I quickly realized this shift was mainly due to a student group called the Smith College Lesbian Alliance, or the SCLA, bringing me closer to answering my why and how questions. Then, however, more questions arose about why this shift at Smith happened at the tail end of the first wave of the gay liberation movement, instead of during. So many civil rights movements have been youth and student driven, so why not this one?

Part of this answer came with a bit of digging into Jill Ker Conway, Smith’s president from 1975 to 85. Despite being Smith’s first female president and self-proclaimed feminist, Conway was not supportive of the lesbian community, especially on Smith campus. During the second year of her term, Conway released a “Statement on Lesbianism” that stated, quote “the charge of lesbianism in women’s communities, whether true or false, has been used to undermine the integrity and vitality of women’s social life,” end quote. In the 1983 winter alumnae quarterly, Conway’s address also explicitly names the SCLA, as a quote “very threatened and nervous group of people,” end quote. In the same address she claims that the Alliance’s membership was limited to about 40 students.

I questioned these comments, knowing that Smith has long been known as a lesbian hub, and wondering how that would be possible with fewer than fifty queer voices on campus merely forty years ago. So I took my investigation straight to the source: the documents of the SCLA itself. And it didn’t take me long to strike gold: the SCLA’s Spring 1982 Student Survey. The SCLA asked one member in each house to solicit housemates who were presumed or known to be gay, including those not active in the Alliance. That spring, 124 students completed the over 350 question questionnaire. The survey was kept completely anonymous, even from those analyzing the data, with each participant being assigned a number to keep track of the continuity of responses.

The respondents came from all four years of undergraduate, ranging from the ages of 17 to 23. 17 out of the 124 students or 13.7% identified as non-white, actually a proportionately larger percentage than the racial breakdown of the whole school at the time. 47% of respondents said they identified as lesbians, with the other 53 being distributed across bisexual, asexual and straight identities. Interestingly, 6 respondents identified themselves as heterosexual, despite the survey being for students known or suspected of being sapphic. 25 participants, however, believed their housemates would say they were heterosexual. This goes to show that no matter how many members of the community a singular student suspected of being queer, chances were about 15% more self-identified in that way.

The most valuable part of this survey, however, does not come in the form of statistics or percentages, but rather from anonymous elaborations left by participants in response to many of the questions, particularly in reference to queer students’ interactions with the college’s faculty and administration. Participants recalled hurtful and homophobic encounters with the adults meant to have the best interest of students in mind like deans and other members of the administration. Participant number 114’s advisor called lesbianism “the perversion that had been gaining strength on campus,” mirroring Conway’s language both about the problematic nature of queer students and the idea that the presence of these voices on campus was new. Participant 57 called her discussion with her dean about lesbianism “frustrating, embarrassing, painful, and belittling.” Overall, participants almost unanimously agreed that the group on campus least receptive and open to lesbian issues were male administrators.

But if student’s faced so much adversity from the school’s highest authorities, how did they persist, how did they find community, and how did we get here? That answer comes in the form of professors, coaches, house councils, friends, and relationships. Smith’s lesbian students carved their own paths and built their communities against the wishes of President Conway and her administration. Many participants noted gay male professors and queer student leaders who made them feel accepted on campus. 86% of participants also noted that half or more of their friends identified within the LGBTQ community. The institution’s loudest voices may have been uncomfortable with lesbians on campus, but it’s in these quiet pockets of support that we build community and make lasting change.

~ ~ ~

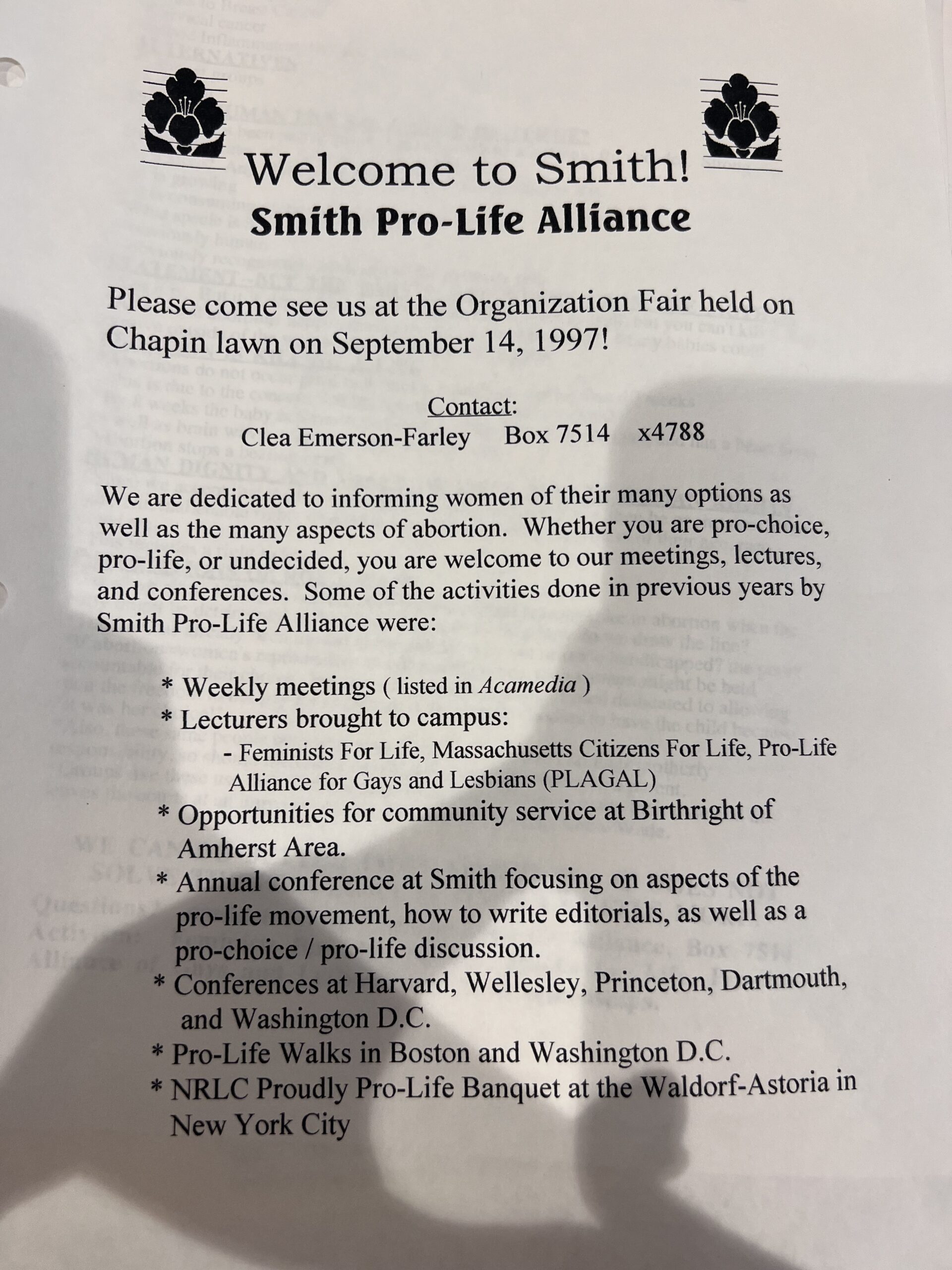

As the eighties went on, and President Conway left her position at Smith, the SCLA only grew louder and stronger. The group rebranded to the LBTA, or Lesbian Bisexual Transgender Alliance, inviting in voices of other queer and marginalized students at the college. The group became far more involved in the political climate and conversation of the time, joining gay liberation marches and national actions.

In my investigation I learned a lot, most importantly being that Smith has always been queer. Women’s colleges have always been a place where young women experience the world for the first time, and queer people exist in every space, no matter how hard history tries to deny it. Young queer women have always found themselves and one another at Smith, and it only harms our history to label this phenomenon as a recent development. The other greatest takeaway I gained from this study is a great appreciation for the SCLA and the young women who played a central role shifting Smith towards the sapphic haven we know and love today.

This has been “The Rise of Lesbianism at Women’s Colleges: SCLA in the 1980s.” Thank you for listening.

References

- “Alumnae Council 1982: Address By President Conway.” Smith Alumnae Quarterly 74, no. 2 (Winter 1983): 21.

- Lesblia, Bisexual, Transgender Alliance records, Smith College Archives, SSC-MS 00112. Boxes 3016 & 3016.1. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/resources/16

- Greene, David A. The women’s movement and the politics of change at a women’s college: Jill Ker Conway at smith, 1975-1985. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Mehren, Elizabeth. “Smith Faces up to Its Reputation on Sexuality.” Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1991. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-12-19-vw-981-story.html.

- M.P. “Homosexuality.” The Sophian (Northampton, MA), February 4, 1971.

- Smith LGBA. “Smith College Lesbian Alliance Student Survey.” 1983. 3016.1. Smith College Archives. Smith College, Northampton, MA.