Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/

repositories /2/archival_objects/134251 Accessed October 23, 2024.

Medical protocol has historically encountered grey area when regarding disabled patients, particularly in conjunction with life altering procedures and decisions. “Disguised Eugenics? Disability and the ‘Right to Life’ Argument” explores how disability rights advocacy has clashed with reproductive justice, exploring topics like abortion, prenatal testing, and wrongful birth lawsuits over the second half of the 20th century.

Transcript

Born in 1967, Phillip Becker was a child with Down’s syndrome who was discovered to have a cardiac problem in 1973. At this time, his parents refused to allow a procedure that would treat this issue. Again in 1977, Phillip underwent medical examination, and doctors recommended that he receive the procedure that would cure his cardiac problems. In response, Phillip’s parents, the Becker couple, requested a psychological evaluation for Phillip. In the end, they denied the surgery, which was predicted to prolong Phillip’s life by 20 years, and Phillip’s case made it to the California Supreme court.1

Amongst the arguments made, the most prominent in favor of the surgery, were that Phillip’s IQ rested amongst the higher percentage of that of the average child with Down’s syndrome. Insinuating discrimination by those who opposed the surgery, Deputy State Attorney General William Stein testified that if it was any other child without Phillip’s condition, it would be without question that the surgery would be performed. On the other hand, those against the surgery questioned what the quality of Phillip’s life would be, with his parents fearing that Phillip would be taken advantage of if he outlived them. One pediatrician was quoted as saying that he considered Phillip’s life “devoid of those qualities which give it human dignity.” Ultimately, the courts decided that on the basis of the Becker’s couple’s concerns that Phillip might outlive them, that they would not mandate the surgery.2

This is Mina Okamoto on “Disguised Eugenics? Disability and the ‘Right to Life’ Argument” and today I’ll be briefly discussing the trends of medical practices, reproductive rights, and prenatal testing in the context of disability rights advocacy over the latter half of the 20th century.

If we examine the main arguments in the Becker case, they tend to revolve around this idea of “quality of life.” In favor of the surgery, doctors cited Phillip’s IQ as an indicator that his life was worth preserving. The argument of the other side was, as mentioned previously, Phillip’s life would be quote devoid of those qualities which give it human dignity. These arguments center around capitalist notions of productivity, and the idea that what somebody contributes to society is equal to their value as a human and right to life. As a result, they bear a frightening resemblance to central tenets of eugenics, which advocate for the suppression of genetic abnormalities.3

Although these ideas may seem like specters of the past, eugenic concepts of genetic optimization have persisted in different forms in the present day. Emerging technologies of prenatal genetic testing like amniocentesis as well as breakthroughs in the field of genetic engineering have introduced moral questions that have become larger than a conversation between two expecting partners. In one way, they have reached the legal system, manifesting as “wrongful birth lawsuits.”

What is a wrongful birth lawsuit? A wrongful birth lawsuit is a case brought to court by the parents of a disabled child against the prenatal care provider. The premise of the case is that the parents had not been given the full information about the child’s condition prior to birth, and that had they understood the extent of the child’s disability, they would have made the choice to abort the pregnancy.4 Wrongful birth lawsuits employ a concept called “wrongful life,” which is an argument that the child themself is harmed by their birth due to their disabilities.5

The first wrongful birth lawsuit emerged in 1967, in a case of a mother suing her physician for advising her to carry her pregnancy to term despite the fact that she contracted rubella, which resulted in a severely disabled child. Notably, this revolutionary late 1960s case coincided with the popularization of amniocentesis testing, which can screen for several disabilities before a child is born, in American medicine.6

So what are the consequences of screening potential disabilities or diseases amongst fetuses before birth? It may seem like the natural step towards ensuring healthy children, but the reality is that it leads to so many more questions. For instance, if expecting parents learn that their baby will be born with a disability, should it be their choice to abort it? On what grounds are they aborting it: is it because they cannot handle the financial burden of caring for a disabled child? Is it because the child does not fit in with their idealized fantasy of a traditional family? Is it because they believe that the child will suffer more by living than by not living at all? In that case, what determines whether a life is worth living: is it based on what one brings to their relationships to others or is there simply an inherent value to all human life. All of these questions are at the root behind an unlikely alliance between disability advocacy and pro-life philosophy.7

Disability advocacy rests on the idea that the difficulties of living with disability are not because of one’s individual disability, but with larger scale social discrimination and failure to accommodate disability. With this rhetoric, anti abortion disability advocates argue that abortions on the basis of forecasted disability only serve to stigmatize the disabled community further.8

The ethical intersection of abortion with prenatal testing has merged two unexpected political groups: the traditionally conservative pro-life school of thought, and the more progressive disability rights movement. In one dimension, pro-life advocates have politicized disability, by emphasizing the value of all human life regardless of life experience and able bodiedness, although oftentimes these same advocates don’t necessarily follow through by supporting programs that help accommodate the needs of disabled individuals. Although disability rights advocates don’t always use the same rhetoric, their end goal aligns with that of pro-life agenda: to reduce or at least call into question the topic of abortion.9

It would be an understatement to say that there is a tenuous relationship between disability rights and medical practice, particularly concerning reproductive justice. In the legal sphere rests the question of whether it should be public responsibility to establish rights for disabled fetuses, or if that is an encroachment on reproductive freedom. In the social sphere lies the conflict between upholding the reproductive justice tenet of the right not to have children and what the implications of aborting a disabled fetus are: whether that means disabled life is worth less than an able bodied life is. And of course, there is a difference on a case by case basis: whether that is socioeconomic status, experience with disability, political ideology, or psychological state of expecting parents.

As technology surrounding pregnancy and childbirth advances, the responsibility more and more rests on individuals to determine their own values. How can we balance reproductive rights while avoiding stigmatizing the disabled community? I hope you continue to ponder these ideas as we step into the age of genetic engineering and designer babies. This has been Mina Okamoto with “Disguised Eugenics? Disability and the ‘Right to Life’ Argument.” Thanks for tuning in.

- Annas, “Law and the Life Sciences: Denying the Rights of the Retarded: The Phillip Becker Case,” 18-20 ↩︎

- Box 9, Folder 12. SSC-MS-00576 Reproductive Rights National Network Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass ↩︎

- Annas, “Law and the Life Sciences: Denying the Rights of the Retarded: The Phillip Becker Case,” 18-20 ↩︎

- Jillian T. Stein, “Backdoor Eugenics: The Troubling Implications of Certain Damages Awards in Wrongful Birth and Wrongful Life Claims,” Seton Hall Law Review 40, no. 3 (2010): 1117-1168 ↩︎

- Silva, “Lost Choices and Eugenic Dreams: Wrongful Birth Lawsuits in Popular News Narratives,” 26-27

↩︎ - Daniilidis, A et al. “A four-year retrospective study of amniocentesis: one centre experience,” 113.

↩︎ - Stefanija Giric, “Strange Bedfellows: Anti-Abortion and Disability Rights Advocacy,” 741

↩︎ - Stefanija Giric, “Strange Bedfellows: Anti-Abortion and Disability Rights Advocacy,” 741

↩︎ - Stefanija Giric, “Strange Bedfellows: Anti-Abortion and Disability Rights Advocacy,” 741

↩︎

References

Annas, George J. 1979. “Law and the Life Sciences: Denying the Rights of the Retarded: The Phillip Becker Case.” The Hastings Center Report 9 (6): 18–20. doi:10.2307/3561672.

Bagenstos, Samuel R. 2006. “Disability, Life, Death, and Choice.” Harvard Journal of Law & Gender 29 (2): 425–63. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=3080218d-0902-39d0-977f-ea8f41c28fb5.

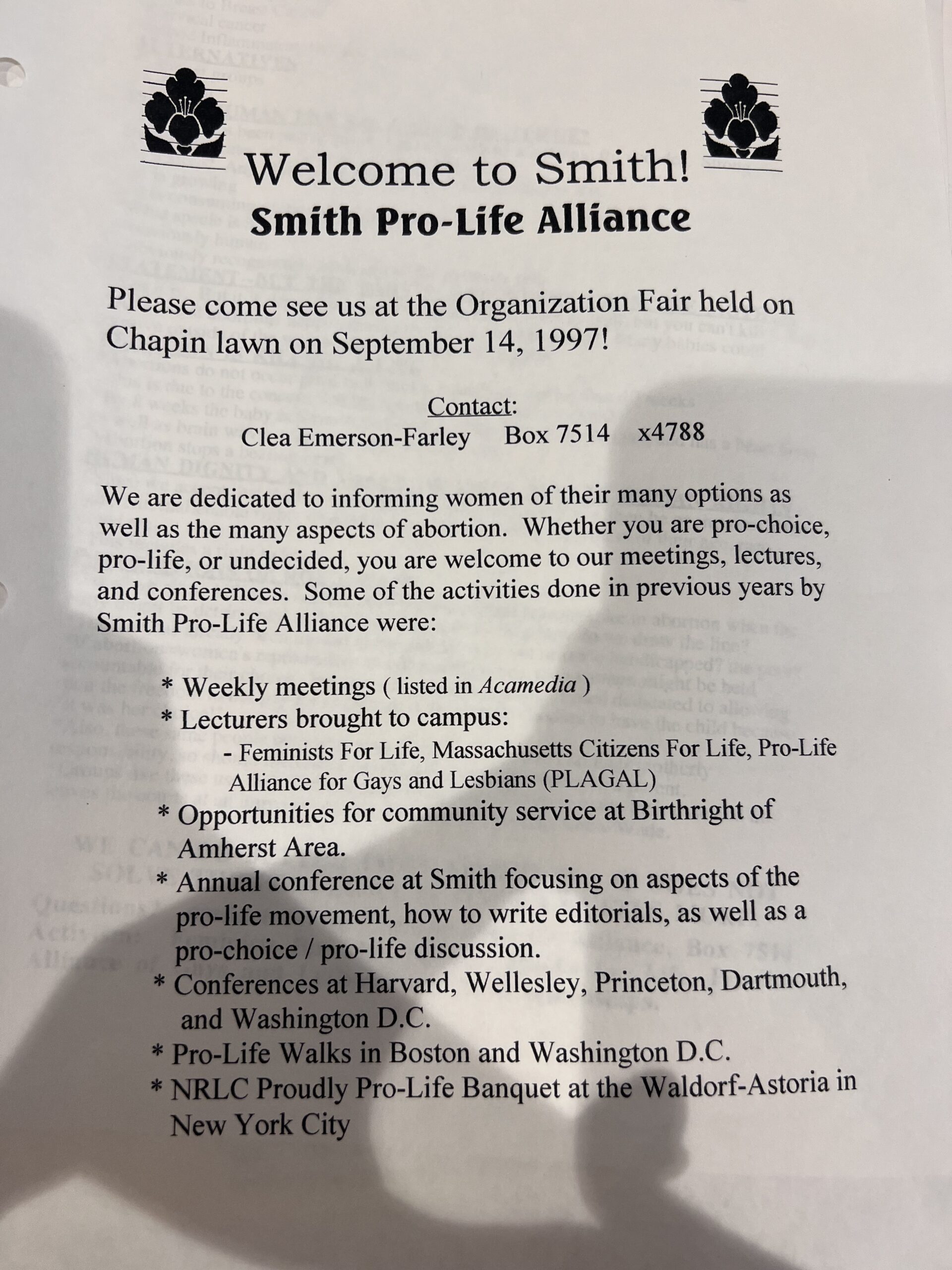

Box 9, Folder 12. SSC-MS-00576 Reproductive Rights National Network Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories /2/archival_objects/134251 Accessed October 23, 2024.

Chastain, Madison. 2022. “I’m an Anti-Abortion Disability Advocate: Overturning Roe Isn’t the Answer.” National Catholic Reporter 58 (18): 13. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=ae93767f-8320-397f-a70e-2c22604fcffd.

Daniilidis, A et al. “A four-year retrospective study of amniocentesis: one centre experience.” Hippokratia vol. 12,2 (2008): 113-5.

Jillian T. Stein, “Backdoor Eugenics: The Troubling Implications of Certain Damages Awards in Wrongful Birth and Wrongful Life Claims,” Seton Hall Law Review 40, no. 3 (2010): 1117-1168

Silva, VestaT. 2011. “Lost Choices and Eugenic Dreams: Wrongful Birth Lawsuits in Popular News Narratives.” Communication & Critical/Cultural Studies 8 (1): 22–40. doi:10.1080/14791420.2010.543985.

Stefanija Giric, “Strange Bedfellows: Anti-Abortion and Disability Rights Advocacy,” Journal of Law and the Biosciences 3, no. 3 (December 2016): 736-742

Transcript

Born in 1967, Phillip Becker was a child with Down’s syndrome who was discovered to have a cardiac problem in 1973. At this time, his parents refused to allow a procedure that would treat this issue. Again in 1977, Phillip underwent medical examination, and doctors recommended that he receive the procedure that would cure his cardiac problems. In response, Phillip’s parents, the Becker couple, requested a psychological evaluation for Phillip. In the end, they denied the surgery, which was predicted to prolong Phillip’s life by 20 years, and Phillip’s case made it to the California Supreme court.

Amongst the arguments made, the most prominent in favor of the surgery, were that Phillip’s IQ rested amongst the higher percentage of that of the average child with Down’s syndrome. Insinuating discrimination by those who opposed the surgery, Deputy State Attorney General William Stein testified that if it was any other child without Phillip’s condition, it would be without question that the surgery would be performed. On the other hand, those against the surgery questioned what the quality of Phillip’s life would be, with his parents fearing that Phillip would be taken advantage of if he outlived them. One pediatrician was quoted as saying that he considered Phillip’s life “devoid of those qualities which give it human dignity.” Ultimately, the courts decided that on the basis of the Becker’s couple’s concerns that Phillip might outlive them, that they would not mandate the surgery.

This is Mina Okamoto on “Disguised Eugenics? Disability and the ‘Right to Life’ Argument” and today I’ll be briefly discussing the trends of medical practices, reproductive rights, and prenatal testing in the context of disability rights advocacy over the latter half of the 20th century.

If we examine the main arguments in the Becker case, they tend to revolve around this idea of “quality of life.” In favor of the surgery, doctors cited Phillip’s IQ as an indicator that his life was worth preserving. The argument of the other side was, as mentioned previously, Phillip’s life would be quote devoid of those qualities which give it human dignity. These arguments center around capitalist notions of productivity, and the idea that what somebody contributes to society is equal to their value as a human and right to life. As a result, they bear a frightening resemblance to central tenets of eugenics, which advocate for the suppression of genetic abnormalities.

Although these ideas may seem like specters of the past, eugenic concepts of genetic optimization have persisted in different forms in the present day. Emerging technologies of prenatal genetic testing like amniocentesis as well as breakthroughs in the field of genetic engineering have introduced moral questions that have become larger than a conversation between two expecting partners. In one way, they have reached the legal system, manifesting as “wrongful birth lawsuits.”

What is a wrongful birth lawsuit? A wrongful birth lawsuit is a case brought to court by the parents of a disabled child against the prenatal care provider. The premise of the case is that the parents had not been given the full information about the child’s condition prior to birth, and that had they understood the extent of the child’s disability, they would have made the choice to abort the pregnancy. Wrongful birth lawsuits employ a concept called “wrongful life,” which is an argument that the child themself is harmed by their birth due to their disabilities.

The first wrongful birth lawsuit emerged in 1967, in a case of a mother suing her physician for advising her to carry her pregnancy to term despite the fact that she contracted rubella, which resulted in a severely disabled child. Notably, this revolutionary late 1960s case coincided with the popularization of amniocentesis testing, which can screen for several disabilities before a child is born, in American medicine.

So what are the consequences of screening potential disabilities or diseases amongst fetuses before birth? It may seem like the natural step towards ensuring healthy children, but the reality is that it leads to so many more questions. For instance, if expecting parents learn that their baby will be born with a disability, should it be their choice to abort it? On what grounds are they aborting it: is it because they cannot handle the financial burden of caring for a disabled child? Is it because the child does not fit in with their idealized fantasy of a traditional family? Is it because they believe that the child will suffer more by living than by not living at all? In that case, what determines whether a life is worth living: is it based on what one brings to their relationships to others or is there simply an inherent value to all human life. All of these questions are at the root behind an unlikely alliance between disability advocacy and pro-life philosophy.

Disability advocacy rests on the idea that the difficulties of living with disability are not because of one’s individual disability, but with larger scale social discrimination and failure to accommodate disability. With this rhetoric, anti abortion disability advocates argue that abortions on the basis of forecasted disability only serve to stigmatize the disabled community further.

The ethical intersection of abortion with prenatal testing has merged two unexpected political groups: the traditionally conservative pro-life school of thought, and the more progressive disability rights movement. In one dimension, pro-life advocates have politicized disability, by emphasizing the value of all human life regardless of life experience and able bodiedness, although oftentimes these same advocates don’t necessarily follow through by supporting programs that help accommodate the needs of disabled individuals. Although disability rights advocates don’t always use the same rhetoric, their end goal aligns with that of pro-life agenda: to reduce or at least call into question the topic of abortion.

It would be an understatement to say that there is a tenuous relationship between disability rights and medical practice, particularly concerning reproductive justice. In the legal sphere rests the question of whether it should be public responsibility to establish rights for disabled fetuses, or if that is an encroachment on reproductive freedom. In the social sphere lies the conflict between upholding the reproductive justice tenet of the right not to have children and what the implications of aborting a disabled fetus are: whether that means disabled life is worth less than an able bodied life is. And of course, there is a difference on a case by case basis: whether that is socioeconomic status, experience with disability, political ideology, or psychological state of expecting parents.

As technology surrounding pregnancy and childbirth advances, the responsibility more and more rests on individuals to determine their own values. How can we balance reproductive rights while avoiding stigmatizing the disabled community? I hope you continue to ponder these ideas as we step into the age of genetic engineering and designer babies. This has been Mina Okamoto with “Disguised Eugenics? Disability and the ‘Right to Life’ Argument.” Thanks for tuning in.