By Isabel Johnson

The phenomenon of men believing they are better and more athletic than all women is commonplace. This podcast covers the reasoning behind this mindset and how it has affected women’s athletics today, from media coverage to professional athletes’ pay, and how women’s sports are playing a crucial role in the current wave of feminism.

Transcript- Sexism in Sports: Why Average Men Think They Could Beat Professional Female Athletes

Have you ever seen those Instagram reels where men are asked whether they could beat a professional female athlete at her own sport, and they confidently say they could? Or that viral clip of pro golfer Georgia Ball at a golf range, where a man “corrects” her swing? Or even the story about Molly Seidel, the Olympic medalist, who had a man on a flight give her unsolicited marathon advice, pulling up a “random pro runner’s” training plan that turned out to be her own?

These events are widespread and raise the question- why do so many men believe they could outperform elite female athletes if they really wanted to? Let’s take a closer look.

To start, let’s look at some research done by Psychologist Robin Schrodter that examined why sports environments often produce sexist attitudes. He found that competitive settings tend to foster antisocial personality traits such as narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. These traits correlate with negative behaviors such as aggression or dishonesty, but these same behaviors can also help people succeed in high-pressure arenas like sports or the workplace. Because of this, many athletes score higher on measures of these “dark personality traits.”

Importantly, these traits often include hostile sexism, especially in individuals who see the world through a competitive lens. Schrodter discovered that there wasn’t a major difference in these traits between professional athletes and men who simply played club sports. This suggests that sexism within sports culture isn’t limited to the pros, but that it emerges from the broader culture of competition many men grow up in.

Writer Cindy Kuzma explored a similar question about why is sexism in sports so persistent. While competitiveness may amplify sexist attitudes, the deeper root lies in our heteronormative social norms. Psychologists explain that boys are taught from a young age that they are “supposed” to be stronger, faster, and more athletic than girls, that this is simply “biology.” When this belief becomes ingrained early on, it shapes how men view women athletes later in life. Even when women achieve at elite levels, many men still believe they should naturally be better, which is how you end up with 1 in 8 men thinking they could score a point on Serena Williams.

This ingrained mindset feeds into the dark personality traits that shape many men’s perceptions of women’s sports.

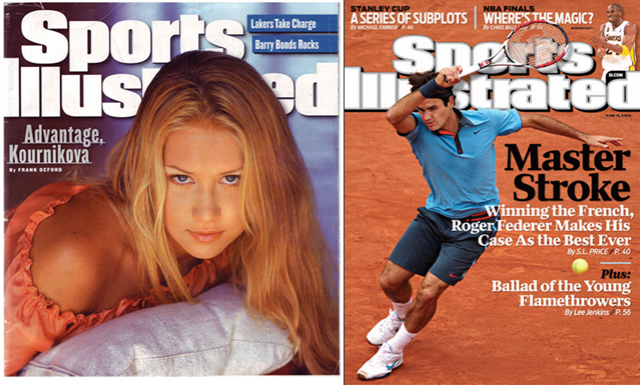

We see the effects of this everywhere in the media. Women’s sports receive far less coverage, partly because people assume they’re “less interesting” due to differences in speed or strength.This makes it to when women are covered, the focus often shifts to their appearance instead of their athletic ability.

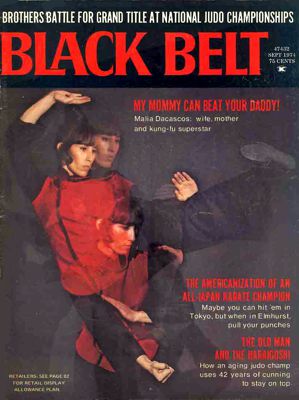

Similarly, top athletes like Malia Bernal, who was known for outpreforming men and placing first in mens fighting tournoments, were interviewed mostly about their femininity rather than their skill. Her magazine feature, that can be found in the Smith archives, asked her question like whether she still “felt feminine” and emphasized slogans like “My mommy can beat your daddy,” focusing more on gender than athletic excellence. Unlike the men interviewed in the same magazine she wasn’t asked about her training, strategy, or mindset the way male athletes routinely were.

Research by Gomez-Gonzalez, Dietl, Berri, and Nesseler highlights just how deep this bias runs. In their study, participants watched videos of women’s soccer goals. One group saw the unedited footage of the women; the other saw blurred footage that hid their gender. The results were unsurprisingly that the group who knew they were watching women rated the gameplay lower and said they wouldn’t pay to watch it. While those who watched the blurred version rated it higher and said they would pay. The skill was the same, the only difference was perception.

This kind of bias is exactly why women athletes struggle to be taken seriously. And yet, the logic doesn’t hold up. Fans love college sports, even though college athletes are slower and less physically developed than pros. So why is it different when it comes to women? Why are they compared to men when playing instead of just being seen for their own merit?

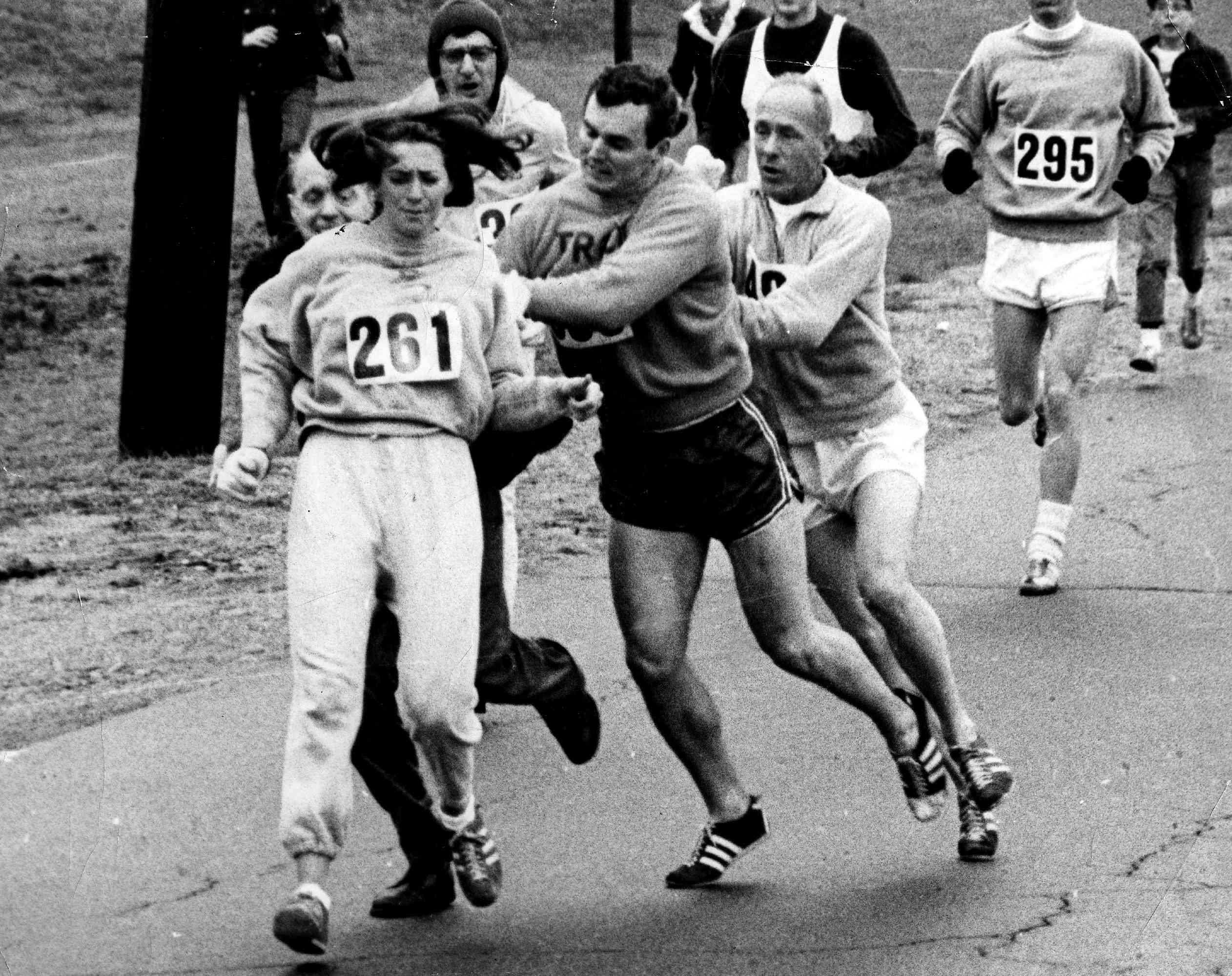

This pattern in coverage isn’t new; it’s been part of women’s sports media from the beginning. In 1994, the Women’s Sports Foundation released Words to Watch, a set of guidelines urging journalists to treat women’s and men’s sports equally. The guide asked media outlets to reflect on the messages they were sending through images and descriptions of female athletes through a series of questions. Some questions were straightforward, like “Does she look like an athlete?” calling out common practices at the time where media outlets would use photos of women only when they looked uncoordinated, or choosing pictures of them in everyday clothing instead of their uniforms. One guideline asked, “Are any significant body parts missing?” because so many outlets published images of female athletes with their heads cropped out, reducing them to their bodies alone.

The report also criticized how commentators talked about women on air. Referring to female athletes without using their names, minimizing their identities and achievements. They would also often discuss women’s physical traits, a practice only done to women. After all, no one talks about the male athletes performing by saying “6’2 with luscious brown hair and baby blue eyes,” yet this kind of commentary was, and in many cases still is, common for women.

Despite these challenges, women athletes aren’t backing down, bringing the same competitive drive as men, and they’re pushing the sports world into a new era. With stories such as Jasmin Paris collapsing over the Barkley Marathon finish line, Serena Williams winning yet another Olympic gold, and Caitlin Clark drawing unprecedented attention to women’s basketball, all show the strength of this movement.

This new era of womens sports is demanding their visability and their athletic prowice to be recognized without being belittled by men. Their growing visibility has helped increase media coverage of women’s sports from 4% of all sports media to 12%. This era is also brining in more fans with more people than ever tuning into the women’s Division I basketball championship, which doubled the viewership of the men’s game. The WNBA draft drew a record-breaking 2.5 million viewers.

More female athletes than ever are making marketing deals with big companies, and are refusing to rely on provocative images

Despite this, inequities remain when it comes to pay. The average WNBA salary is $76,500, compared to the NBA’s $1.1 million—a staggering gap.

Sexism in sports didn’t emerge overnight; it was built over generations through media portrayals, cultural expectations, and the belief that men are the natural standard of athleticism. For decades, women have been judged not by their talent, but by how closely they fit into someone else’s idea of what an athlete “should” look like. And while today’s athletes are rewriting the story, the legacy of those early biases still lingers in everything from pay gaps to online commentary. Yet the progress we’re witnessing proves that sexism in sports is not fixed, it’s constructed, and therefore it can be dismantled. As more women dominate headlines, command massive audiences, and reshape what athletic excellence looks like, it becomes harder to cling to outdated assumptions. The future of sports will depend on whether we choose to keep measuring women against men—or finally recognize their achievements on their own terms. Women athletes have already shown they belong; now it’s up to the rest of the world to catch up.

References

Ribner, Susan. Papers. SSC-MS-00725. Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

Gomez-Gonzalez, Carlos, Helmut Dietl, David Berri, and Cornel Nesseler. “Gender Information and Perceived Quality: An Experiment with Professional Soccer Performance.” Sport Management Review 27, no. 1 (2024): 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2023.2233341

Schrödter, Robin. “The Dark Core of Personality and Sexism in Sport.” Personality and Individual Differences (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(21)00498-0

Levene, Ali. “Women’s Sports Isn’t ‘Having a Moment.’ It’s a Movement, New Study Shows.” RUN | Powered by Outside, November 12, 2024. https://run.outsideonline.com/news/womens-sports-isnt-having-a-moment-its-a-movement-new-study-shows/

Kuzma, Cindy. “We Asked a Psychologist Why So Many Average Men Think They Can Beat a Top Female Athlete in Her Sport.” SELF, April 29, 2024. https://www.self.com/story/why-men-mansplain-sports-to-female-athletes.

Coleman, Doriane Lambelet, and Wickliffe Shreve. Comparing Athletic Performances: The Best Elite Women to Boys and Men. Duke University Sports Law Center, 2018. https://law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/sportslaw/comparingathleticperformances.pdf

Women’s Sports Foundation. Media: Images and Words in Women’s Sports—The Foundation Position. August 2016. https://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/media-images-and-words-in-womens-sports-the-foundation-position.pdf

Getty Images. “Kathrine Switzer.” Accessed December 2025. https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/kathrine-switzer

Gallery Image References:

Black Belt Magazine. September 1974. Cover photograph.

Small, Tricia. “Sociological Perspectives: Gender Bias in Sports Coverage.” Gender Bias in Sports (blog). November 15, 2012. https://genderbiasinsports.blogspot.com/2012/11/blog-post_15.html

Gomez-Gonzalez, Carlos, Helmut Dietl, David Berri, and Cornel Nesseler. “Gender Information and Perceived Quality: An Experiment with Professional Soccer Performance.” Sport Management Review 27, no. 1 (2024): 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2023.2233341