Malena Gomez

Since the Dobbs decision in 2022, abortion providers and clinic staff have faced increasing incidents of violence and harassment. Although this spike in antiabortion violence may seem rather sudden, the history of violence against abortion clinic workers can be traced back much further. This episode will discuss the history of anti-abortion violence, from the 1980s, after the landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, to the present-day world post-Dobbs.

Transcript

[Intro music]

Between 2023 and 2024 alone, the National Abortion Federation reported over 600 incidents of trespassing at abortion clinics, 200+ reports of death threats against providers, over 30 cases of stalking, and over 30 cases of assault and battery.

In light of the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, the country has witnessed an increase in extremist antiabortion demonstrations and acts of violence and harassment against abortion providers.

But despite the rather sudden spike in antiabortion extremism since the Dobbs decision, the history of such demonstrations can be traced back even further—to more than 50 years ago.

In this episode, I’ll discuss the history of antiabortion violence in the United States, specifically going back to the 1980s, after the landmark Roe v. Wade decision in 1973.

[transition music]

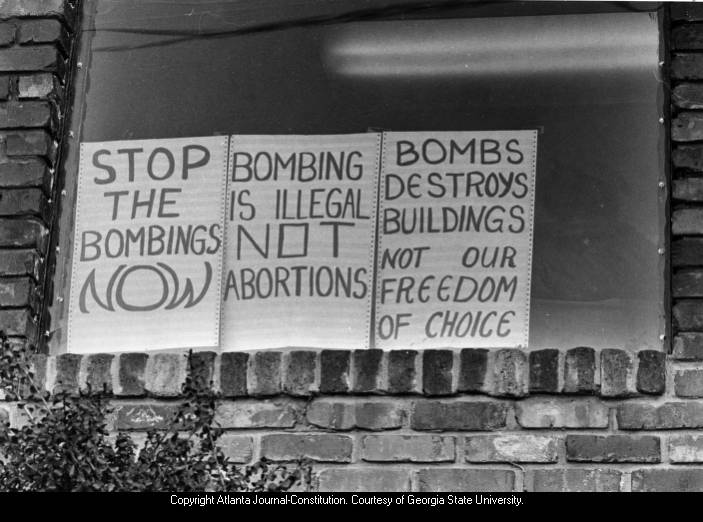

The January 1985 edition of off our backs magazine describes the handling of abortion clinic bombings by the Reagan administration. Quoting Judy Goldsmith, then the president of the National Organization for Women, the article says that, rather than publicly repudiating the bombings, Reagan used “inflammatory rhetoric, even invoking words like ‘murder’ and ‘holocaust’” about abortion.

In other words, Reagan did not publicly denounce the violent attacks on clinics even as they occurred more frequently. But he instead continued to use antiabortion rhetoric that could be used to justify such attacks.

About eight years later, in 1993, Dr. David Gunn was shot and killed in the parking lot behind the Pensacola Women’s Medical Services clinic in Florida. According to a Times article from that same time, “in the eyes of abortion rights activists, the killing of Dr. David Gunn [was] simply the culmination of years of violence [. . .] against clinics.”

In 1994, largely in response to Dr. Gunn’s murder, the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (or FACE) Act was passed. This federal act made the obstruction, via force, threat of force, or physical blockade, of reproductive clinic entrances a crime.

In spite of this, antiabortion violence continued. Just months after its passing, Dr. John Britton was shot and killed alongside volunteer escort James Barret outside of another clinic in Pensacola, Florida.

In that same year, John Salvi walked into two reproductive health clinics in Boston, Massachusetts, and killed receptionists Shannon Lowney and Leanne Nichols.

In 1998, an antiabortion terrorist detonated a bomb outside the New Woman All Women Healthcare clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, killing police officer Robert Sanderson and severely injuring a nurse, Emily Lyons.

Sanderson became the first person to be killed in a bombing of an abortion clinic. Speaking to NPR nearly three decades later, Emily Lyons recalled the attack and her experience as a provider in an abortion clinic:

[NPR news clip] “I didn’t know about the risks when I got the job. When I went to work the first day I was wondering why there was protestors standing out in the streets screaming at me as I was driving in. [. . .] Sandy was very mild-mannered, courteous. He was not pro-choice, but he knew he had a job to do the days he came to the clinic to provide security. It didn’t matter to him why you were there, he was there to protect us. And yes, indeed, on that day his body did protect.”

Unfortunately, for many like Lyons, working in an abortion clinic has represented a threat to safety, security, and wellbeing. Clinic workers are prone to harassment, threats to their lives, threats to their families’ lives, and even physical violence.

In 2009, after years of facing harassment, bomb threats, and actual attempts on his life, Dr. George Tiller was shot and killed while serving as an usher during a church service.

The murder of Dr. Tiller, who had stood his ground as a provider of late-term abortion in urgent cases, sparked a wave of outrage and fear for the fate of clinics across the country.

Using a fake name, Kristina Romero spoke to Times magazine in 2015 about her experience as a worker in an abortion clinic.

Describing the harassment she faced working in a clinic in a conservative state, she said, “They call you by name. They know your kids’ names. They know your mom and dad’s names. They know where you go to church.” Kristina described the threats she faced in the mail, notes describing the car she drove and where she drove it. She’d even been followed home at least once.

There are many stories like Kristina’s, stories of abortion care workers facing violence and harassment firsthand. But even for those who haven’t experienced it firsthand, there is the constant fear of being targeted, the fear that—like Dr. Gunn, Shannon Lowney, Leanne Nichols, Dr. Tiller, or many others—they won’t make it home to their families.

[transition music]

But where does antiabortion extremism stand today, in the world post-Dobbs?

According to a Rolling Stone article from 2024, “violence against abortion providers has continued to rise” following the 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which stated that abortion wasn’t a Constitutional right.

The National Abortion Federation says that these legal decisions have “emboldened antiabortion extremists,” and post-Dobbs, theres been “an immediate spike in major incidents targeting abortion providers.”

The NAF reported 3,582 incidents of harassment, 12 incidents of bomb threats, 169 incidents of vandalism, and 17 incidents of theft between 2023 and 2024. This is in addition to the reported 621 incidents of trespassing, 296 reports of death threats against providers, 37 cases of stalking, and 38 cases of assault and battery. Its important to note that the NAF believes these incidents to have been underreported, in part due to normalization of such extreme behaviors.

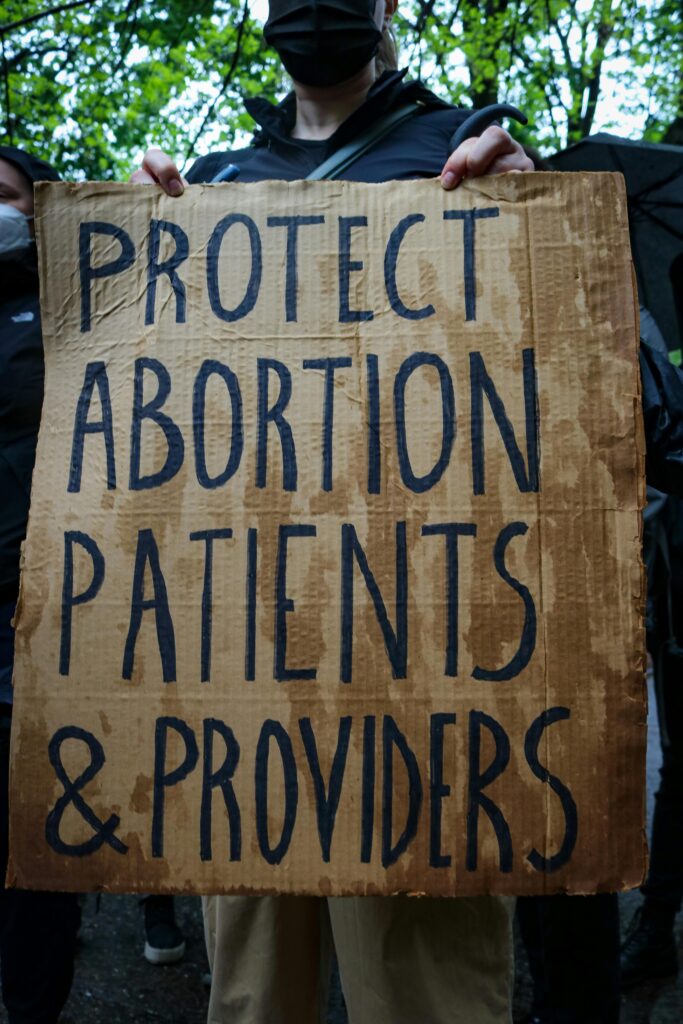

But despite the spike in antiabortion terrorism since Dobbs, abortion providers and clinic defenders have stood their ground to keep clinic doors open.

According to a 2024 article from Rolling Stone, clinic defenders, even when faced with aggressive antiabortion activists, aren’t going anywhere—and many of them have found new ways to adapt.

Since 2020, social media has become a major tool in the work of clinic defenders. According to the Rolling Stone, “Defenders film antagonists and use social media to connect with clinics across state lines and identify repeat offenders, especially those who get violent or cause disruptions.”

Although not all clinic defense groups have been able to adapt, the passion for the important work they do hasn’t faded. These clinic defenders play a critical role in protecting patients and providers from the harassment and violence they face.

At the end of the day, the bravery abortion providers, clinic defenders, and patients is what keeps the doors of these clinics open. In the long history of antiabortion violence, one thing is made clear: abortion clinics aren’t going anywhere, as long as there are people banding together to protect them.

[Emily Lyons for NPR] “Scars just tell people that you were stronger than those who were tried to hurt you. I don’t know what happened during that bomb but it sure flipped a switch in my brain because not much intimidates you once you’ve blown up. You know, life knocks everybody down. But what matters is how you stand up, and we have stood up together.”

References

Cohen, David S., and Krysten Connon. “What It’s Like to Work in an Abortion Clinic.” Time Magazine. 2015. Time.Com.

Diaz, Von. “A Nurse Recalls the 1998 Bombing of an Alabama Health Clinic That Performed Abortions.” NPR. 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/11/15/nx-s1-5191307/a-nurse-recalls-the-1998-bombing-of-an-alabama-health-clinic-that-performed-abortions.

Gray, Paul, and Cathy Booth. “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” Time Magazine, 141 (12) (1993): 44. 9303160941.

Guliani, Emma. “A Person Holding a Rally Poster.” Pexels. Pexels.com

Jones, C. T. “The Abortion-Clinic Defenders Aren’t Going Anywhere.” Rolling Stone, no. 1388 (2024): 36–37.

Mehren, Elizabeth. “Kind Faces, Big Hearts : Violence: Shannon Lowney and Leeann Nichols, Receptionists at Clinics Where Abortions Are Provided, Believed in a Woman’s Right to Choose. And They Died for It.” Los Angeles Times. 1995. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-01-05-ls-16617-story.html.

“NAF 2024 Violence & Disruption Statistics.” n.d. National Abortion Federation. https://prochoice.org/our-work/provider-security/2024-naf-violence-disruption/.

Palmieri, Nancy. “Escorts ushering a woman past police and pro-life protesters into the Providence Planned Parenthood clinic.” 1989. 35 mm photograph. Digital Public Library of America. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/muph074-b04-sl027-i016. (Accessed November 21, 2025.)

Spink, John.“Anti-violence signs in the window of the Feminist Women’s Health Center, Atlanta, Georgia.” 1985. Photograph. Digital Public Library of America. Fulton County, Atlanta, GA. http://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ajc/id/2465

WeVideo. “Mountainscape (No Vocals).” WeVideo Audio Library. Song.

We video. “River Song.” WeVideo Audio Library. Song.

Woehrle, Lori. “Abortion Clinic Bombings and the Reagan Administration.” Off Our Backs 15 (1) (1985): 2–2.

For Further Reading

Jacobson, Mireille, and Heather Royer. “Aftershocks: The Impact of Clinic Violence on Abortion Services.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3, no. 1 (2011): 189–223. edsjsr.10.2307.25760251. https://doi.org/10.2307/25760251.

Slocum, Ava. “Despite Republican Bans and Clinic Violence, Independent Abortion Providers Fight to Keep Their Doors Open.” Ms. Magazine, January 3, 2025. https://msmagazine.com/2025/01/03/independent-abortion-clinic-violence-roe-v-wade-dobbs/.