By Elizabeth Sarpong

This is a podcast that goes over the history of black midwives and their impacts on the past and modern world. It also includes stories of the late Margaret Charles Smith and the founder of the Black Midwifery Collective Star August.

Transcript – The History of Black Midwives

An Urban Wire article titled “A look at the Past, Present, and Future of Black Midwifery in the United States” highlighted how in 2021, it was reported that only 7 percent of certified nurse-midwives identified as Black or African American, despite accounting for 14 percent of the population.

But it hasn’t always been like this..

Midwifery, in fact, has existed for centuries before its first recorded practice in the United States. Midwives were respected back then for bringing their expertise and training to the birthing process. Especially after enslavement, when emancipated African American midwives were important members of their community, midwives were the only viable option for expecting mothers in rural and remote parts of the South because hospitals were rarely accessible and there were few willing or trained doctors to serve black and white women.

Today, I’d like to reflect on the history of African-American midwives, investigate their impact on the past and the present, and find out where all the Black midwives have gone.

We may overlook the advantages of having a well-equipped maternity ward staffed by licensed doctors and nurses today, but these critical tools and personnel were not available to all in the past.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, midwives are healthcare professionals who specialize in pregnancy, childbirth, newborn care, and postpartum health.

Historically, midwifery was the primary form of prenatal care in the United States until the nineteenth century. As a Black, Indigenous, and immigrant female-dominated family profession or apprenticeship, midwives used healing practices passed down from generation to generation in their communities.

As time passed and technology advanced, obstetrics developed and male doctors began to replace midwives, particularly in wealthy white communities. Despite being pushed out of cities and upper-class families, midwives continued to serve Black families in the rural South.

This transition, however, was not simply a phase-out, it was a targeted effort to remove Black midwives from the birthing process. Laws, regulations, and public health campaigns portrayed Black midwives as unqualified or dangerous, despite their long-standing expertise.

Black midwives, both then and now, face systemic barriers to entering the professional maternal health workforce, such as a lack of funding, mentorship, and support.

So after exploring the historical landscape of African American midwives, I wanted to know what this legacy looked like up close. So I turned to Smith College’s Special Collections and there, I found the story of a midwife whose work adds a deeply human layer to this history.

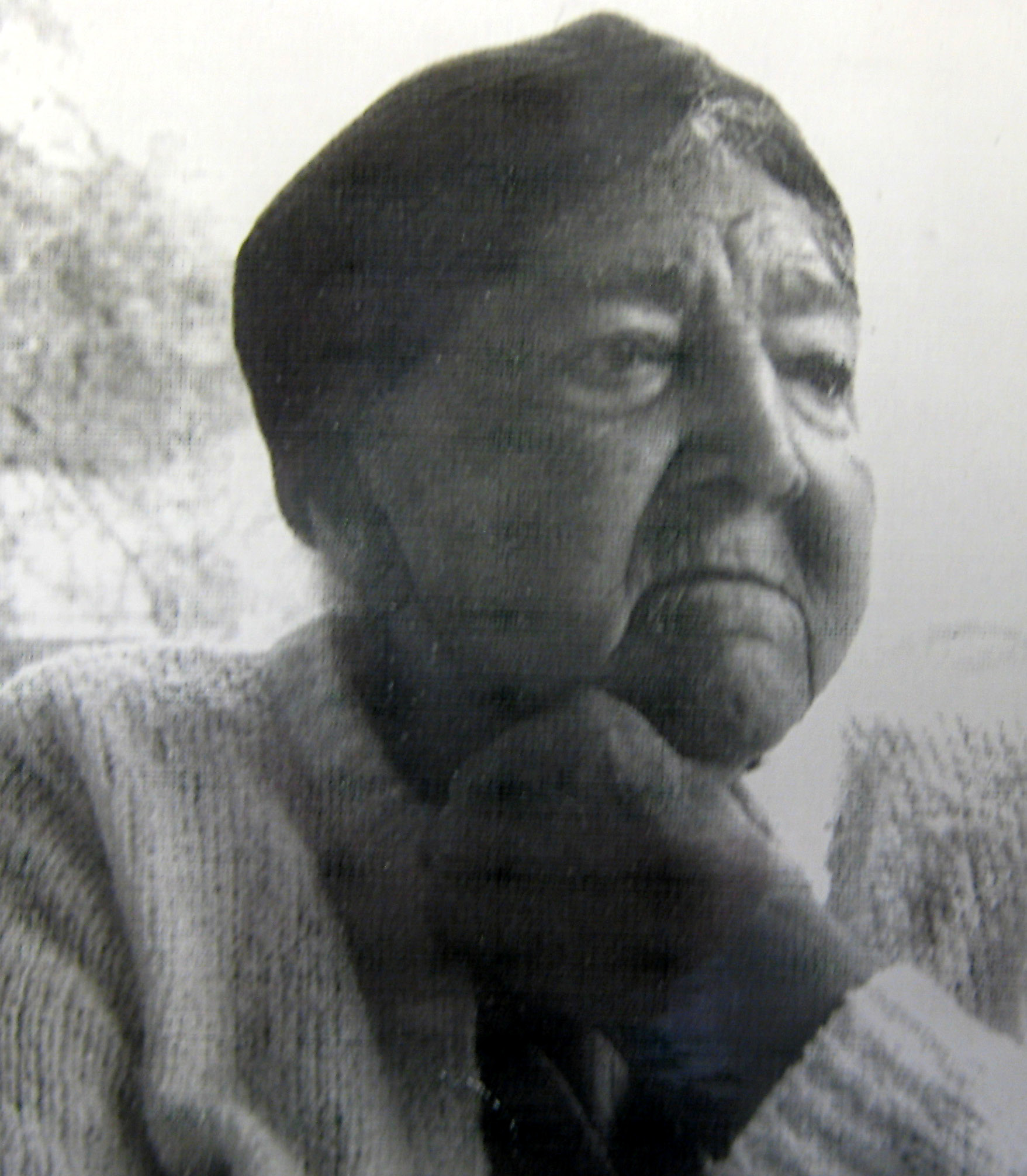

“In a collection titled Linda Janet Holmes’ Oral Histories of African American Midwives, I came across Holmes’ 1981 interview with Margaret Charles Smith. In the interview, Smith talked about her experience as a midwife and what inspired her to enter the profession.

Before she ever caught a baby on her own, Margaret had already spent years caring for others. She helped look after her husband’s first cousin’s wife, a woman raising thirteen children. Margaret was present for many of those births, sometimes even assisting, long before she thought of herself as a midwife. Her calm presence and natural instinct didn’t go unnoticed. A doctor who regularly attended that family began to watch the way Margaret worked. Eventually, he pulled her aside and encouraged her to train as a midwife herself.

By the time of this interview, Margaret had been in the field for nearly thirty years. Nearly three decades of births, of long nights, of walking into homes where she was often the only available healthcare provider. And despite all that experience, she still spoke with a kind humility about where she began and how she almost didn’t pursue this path at all. She admitted she didn’t want to become a midwife at first but looking back, she was glad she did. It became her calling.

What struck me most, though, was her vision for the future. Margaret believed deeply in the importance of midwifery, not just as a tradition, but as something the world might someday need again. She said, ‘I think it’s good for them to practice, because one day all this is going to be vanished away…and you’re gonna have to go back to the midwife.’

It’s almost bizarre how accurate that prediction seems today. Margaret’s words sound more like a prediction than nostalgia at a time when Black maternal mortality is on the rise, hospitals in rural areas are closing, and more families are turning to midwives for culturally competent care.

Margaret Charles Smith’s story reminds us that the wisdom of Black midwives didn’t disappear, it was pushed aside. But it never truly died. And today, there are people working intentionally to revive that legacy and rebuild the systems these women once sustained.

That brings me to the Black Midwifery Collective, an organization created to transform the landscape of maternal health by centering Black birthing people, supporting Black midwives, and confronting the systems that have harmed Black families for generations.

And at the forefront of this work is their founder and executive director, Star August, a midwife and a descendant of a Grand Midwife who practiced in the 1940s.

Star has been immersed in birth work and advocacy for over fifteen years, and her leadership reflects both lived experience and generational inheritance. She stands at the intersection of past and present, carrying the knowledge passed down through her family while building new models of care for the future.

Under her direction, the Black Midwifery Collective isn’t simply providing services, it’s reimagining what care could look like. At the heart of their work is a simple but beautiful belief, one that echoes everything midwives like Margaret Charles Smith knew: that midwives who are empowered to practice in community-based settings, on their own terms, are the best solution to closing the racial gap in maternal and infant outcomes.

What I find so striking is how the Black Midwifery Collective bridges the very questions this podcast is asking. How did we get here? What lessons have we ignored? And how can movements for justice be built not only by challenging harmful systems, but by reviving the practices those systems tried to erase?

In the stories of past midwives, and in the organizing of leaders like Star, we see a continuum of resistance. One rooted in care, community, and the radical idea that every person deserves a birth experience defined by dignity, safety, and support.

And that’s the story we’re still writing today.

Learning about the history of Black midwives, notably Ms. Margaret Charles Smith and Ms. Star August, reminds me that these legacies aren’t just historical footnotes. They are blueprints. They show us what community care once looked like, and what it could look like again.

As we continue to confront today’s maternal health crisis, amplifying these stories isn’t just about honoring the past, it’s about reimagining the future. A future where Black midwives are supported, represented, and valued in the same way they once were in their communities.

Thank you for listening, and thank you for taking this journey with me. Until next time.

References

“About Black Midwifery Collective,” Advocating for Birth Equity, Black Midwifery Collective, https://blackmidwiferycollective.org/about-black-midwifery-collective.

“Healing Legacies: Honoring The History of Black Midwives,” Black Wellness & Prosperity Center, https://www.blackwpc.org/healing-legacies-honoring-the-history-of-black-midwives.

“History of Midwifery,” Honoring Black Midwives & Traditions, Black Midwifery Collective, https://blackmidwiferycollective.org/advocacy-birth-justice/history-of-midwifery.

Lauren Fung and Leandra Lacy, “A Look at the Past, Present, and Future of Black Midwifery in the United States,” Urban Wire, May 18, 2023, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/look-past-present-and-future-black-midwifery-united-states.

Margaret Charles Smith, interview by Linda Janet Holmes, August 29, 1981, transcript, Linda Janet Holmes oral histories of African-American midwives, Sophia Smith Collection, MS-00672, Smith College, Northampton, MA

“The culture war between doctors and midwives explained,” posted May 29, 2018, by Vox, YouTube, 5:59, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SE34K88LUek.

“The Historical Significance of Doulas and Midwives,” National Museum of African American History & Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-significance-doulas-and-midwives.“What is a Midwife? When To See One & What To Expect,” Cleveland Clinic, April 5, 2022, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22648-midwife.

Image Credits

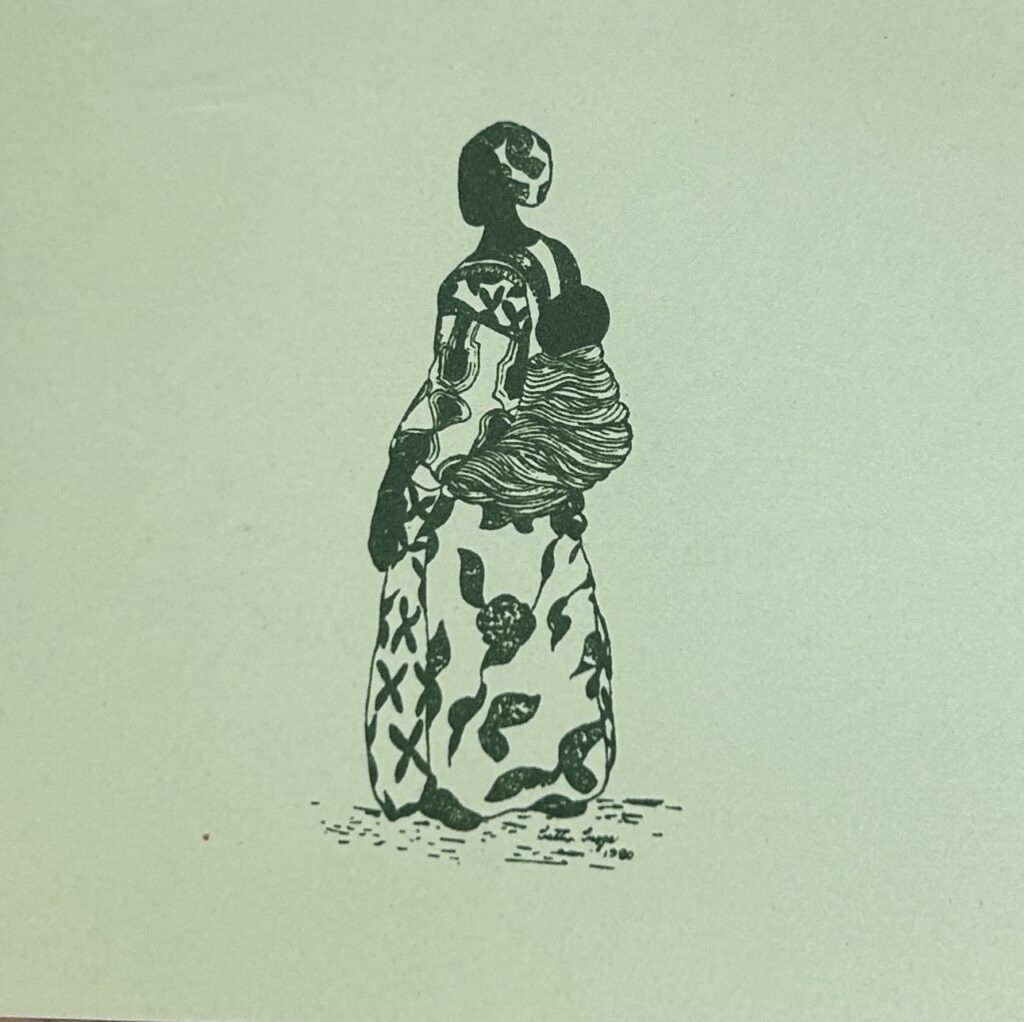

Thumbnail Image: Found in the Linda Janet Holmes’ Oral Histories of African American Midwives which is apart of the Smith College Special Collections. Artist is unfortunately unknown.

Pregnant Woman Photo:https://unsplash.com/photos/silhouette-of-pregnant-woman-tEz8JU1j-00

Photo of Black Midwives: https://www.art.com/products/p14005811-sa-i2846930/w-eugene-smith-nurse-midwife-maude-callen-holds-baby-and-teaches-class-in-midwifery-how-to-look-for-abnormalities.htm?rfid=820685&ranMID=45368&ranEAID=2116208&ranSiteID=TnL5HPStwNw-z5A1.C8yr3v2wYpeZHRuGQ&utm_source=Rakuten&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_publisher=Skimlinks.com

Photo of Margaret Charles Smith: https://www.awhf.org/mcsmith.html

Song Credits

All music belongs to Youtube’s Audio Library

Intro song: good for the ghost by Alge

Song in the middle: Mas Cafe by Casa Rosa

Outro song: Charm by Anno Domini Beats