By: Greta Spitz

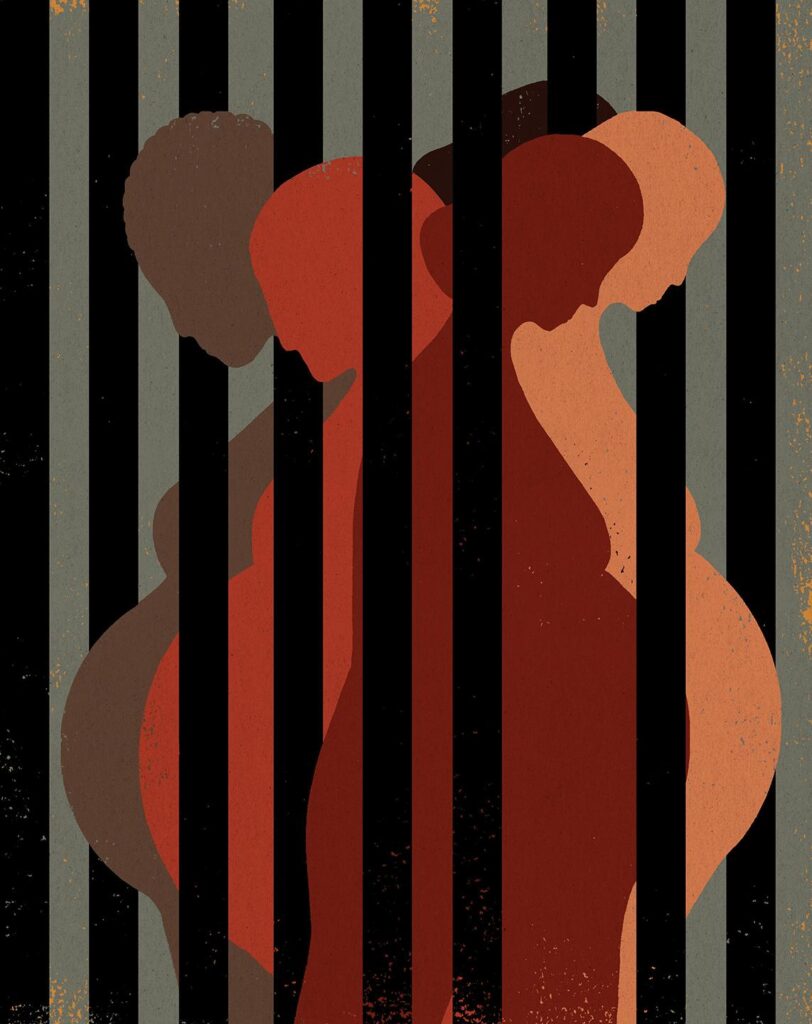

Underreported, underrepresented, and abused, pregnant people suffer in silence within prisons and jails in America. “Birth Behind Bars” focuses on the stories of two women, Jessica Kent and Brittany Seaver, who gave birth while incarcerated, and the in-progress legislation that could save future imprisoned mothers from the trauma they endured.

Transcript: Birth Behind Bars

*Music box cranks and plays a simple melody*

Pregnancy, labor, and birth mark the beginning of a new life for both mother and child.

I want to ask everyone listening to think about their experiences with birth — if you’re a mother, remember the moment you began to bond with your baby. If you’re not, remember every time you’ve seen a new parent hold their child on a walk, gingerly cradling their head as they begin to experience the world together. Remember the joy that circulates through families when even the most distant member brings a new life into the world.

*A sinister music box melody begins to play*

Now imagine if you, or the person who birthed you, were shackled while enduring labor pains. Imagine giving birth alone, or in the presence of prison guards who barely recognize your humanity. Imagine separating a new mother from her child, a mere 24 hours after labor ends. For 4% of incarcerated women, this is their reality. My name is Greta Spitz, and this is “Labor Behind Bars, Fighting The Horrors of an Incarcerated Birth in the United States.”

*Electronic intro music fades in*

Of the 1.5 million women cycling through America’s jail cells each year, an estimated 58,000 of them are pregnant. Their stories are largely unknown; local jail cells fail to provide data surrounding the welfare of pregnant or postpartum people, and experiences that make it to the press are horrifying.

*Electronic intro music fades out*

Jessica Kent, a former drug user and dealer, was incarcerated in a Fort Smith prison at 23 years old. She discovered her pregnancy shortly after receiving a 5-year sentence for drug and firearm possession. At 4:30 am, 9 months later, Jessica woke up from severe back pain in prison. She was going into labor.

*audio clip cue*

JESSICA KENT: “The corrections officer told me to walk to the infirmary. Prison is full of long cordors, long hallways with doors you have to be buzzed through, and I walked in active labor, grinding my teeth, every step more painful than the last, and I thought if I could just get to the infirmary, they’re gonna help me. They’re going to be there and they’re going to help me with my labor and delivery. I’m gonna get to a hospital immediately and everything’s going to be ok, just make it to the infirmary. I knocked on the infirmary door, which you’re not supposed to do, you’re supposed to stand quietly and wait to be buzzed in. Finally they buzz me in, I tell the nurse that I’m in labor, she puts me in a wheel chair with a puppy pad underneath me and I am left there for over four hours.”

*Haunting music fades in*

As you just heard, labor within a jail cell is traumatizing. Jessica was shackled, ignored, and abused during the labor and birth of her child. But for some incarcerated women, the worst has yet to come.

Around two days after birth, the baby and mother are separated.

Brittany Seaver, an expectant mother held in the Minnesota Department of Corrections in Shakopee, was not prepared for the trauma of the separation. Despite having access to a doula who offered words of wisdom and comfort, the reality remained that Brittanty would only have two days to bond with her newborn. She spent those 48 hours awake, manically nursing her daughter Jazzlynn, with a polyester belt fastening her ankle to a nearby chair leg.

The hours slipped away like seconds, soon It was time for Brittany and Jazzlynn to say goodbye. Seaver was placed in a “lockbox” for her journey back to Shakopee. Metal chains wrapped around her legs, ankles, wrists, and torso, rendering her immobile in a wheelchair. Embarrassed, she covered her body with a blanket. A prison guard pushed her down the maternity ward hallways while a nurse wheeled Jazzlynn in a bassinet. Brittany’s tears wet Jazzlyn’s face as she kissed her on the cheeks one final time.

When Jazzlynn was 14 months old, Brittany Seaver asked her mother to stop bringing her to monthly visitations. Jazzlynn had slowly begun to recognize faces, and her mother was disturbingly unfamiliar. She became uncomfortable around Seaver, throwing tantrums when placed in her arms. “My little girl wanted nothing to do with me,” Brittany said.

Let those stories sink in. If you’re as angry as I was when I first heard these women’s experiences, then I can bet you’re thinking, “What can we do to help?” Per usual, the answer is advocacy and Federal policy.

If Brittney had been incarcerated in Missouri, California, Illinois, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, South Dakota, Washington, or West Virginia, she may have had more time with Jazzlyn.

Those ten states have implemented prison nursery programs, but even these are mediocre at best. While such structures provide a safe environment for an inmate to parent their child, time frames vary widely. State to state, a new parent could have as little as 30 days to consistently be around their newborn, with the maximum capping at 30 months. Funding is scarce for nursery programs, resulting in limited resources for safe child-rearing. Qualifications for mothers to participate in such programs, such as a record completely free from violent crimes, also bar people within the ten states from taking advantage of the nurseries.

While 42 states have passed anti-shackling laws, meaning that no person will be restrained during pregnancy or the post-partum period, the enforcement of such legislation is dubious.

Factors like shackling law loopholes, uninformed hospital staff, poor officer training, and blatant cruelty have led to shackled births within states that prohibit them.

State to state laws are not enough. All mothers behind bars deserve rights regardless of their location.

*Haunting music fades out*

*Simple upbeat piano music fades in*

Luckily, congress members recognize this need for federal policy, but first, let’s do a quick logistical recap of pregnancy and prisons: around 58,000 pregnant people are admitted to jails and prisons each year. When taking into account the fact that Black people are incarcerated at a rate 5 times higher than white people, it’s clear that the lack of care for pregnant people in prisons is an intersectional issue.

In 2019, Congresswoman Lauren Underwood and Congresswoman Alma Adams joined forces to create the Black Maternal Health Caucus. Joined by a staggering 53 members, Underwood and Adams fought to reckon with inadequate maternity healthcare for Black women both inside and outside of incarceration.

Quickly becoming one of the largest bipartisan caucuses on Capitol Hill, the Black Maternal Health Caucus spearheaded the development of the Momnibus Act. This legislative package was made up of 13 bills that spanned crises such as maternal mortality, morbidity, inadequate data collection, and funding for housing, nutrition, and mental health support during pregnancy for those in need.

Bill Number 8 is particularly poignant for inmates. The Justice for Incarcerated Moms Act aims to garner funding for the care of incarcerated pregnant and postpartum people, a comprehensive study to document the issues of maternity care behind bars and a financial incentive for state and local prisons and jails to prohibit shackling.

One would think that Bill number 8 of the Momnibus Act would pass unanimously, but sadly, this was not the case. After its first introduction in 2021, the Momnibus Act was reintroduced during the 118th congress on May 18th, of 2023, It was not passed as a collective act, and no individual bills were put into action.in addition Momnibus has not been reintroduced during the 119th Congress.

Luckily, the act was not championed in vain. Individual states have taken heavy inspiration from the Momnibus Act, creating Momnibus-style legislation packages that have the power to greatly improve incarcerated pregnancy.

*Electronic intro music fades back in*

We have a long way to go before giving birth while incarcerated is safe. In a post-Dobbs world where women are expected to stay pregnant no matter the circumstances, it is imperative that we uplift stories of women who are literally shoved out of sight. Reproductive justice should transcend incarceration status; no matter how you stand within America’s criminal justice system , you should be able to safely have a child.

I’m Greta Spitz, and you have been listening to “Labor behind bars.”

References:

Harley, Anna. 2022. “I gave birth in a British prison – no woman should suffer what I went through | Anna Harley.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/mar/28/birth-british-prison-no-woman-handcuffed-labour.

Mondestin, Tanesha. 2024. “A Look at Maternal Health Legislation in the 118th Congress.” The Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2024/10/28/a-look-at-maternal-health-legislation-in-the-118th-congress/#:~:text=While%20most%20components%20of%20the,our%20companion%20appropriations%20blog%20here.

Raman, Nethra. 2024. “Pregnancy in Prison – MacArthur Justice.” MacArthur Justice Center. https://www.macarthurjustice.org/blog2/pregnancy-in-prison/.

Santo, Alysia. 2020. “For Most Women Who Give Birth in Prison, ‘The Separation’ Soon Follows | FRONTLINE.” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/for-most-women-who-give-birth-in-prison-the-separation-soon-follows/.

Santo, Alysia. 2020. “For Most Women Who Give Birth in Prison, ‘The Separation’ Soon Follows | FRONTLINE.” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/for-most-women-who-give-birth-in-prison-the-separation-soon-follows/.

Santo, Alysia. 2020. “For Most Women Who Give Birth in Prison, ‘The Separation’ Soon Follows | FRONTLINE.” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/for-most-women-who-give-birth-in-prison-the-separation-soon-follows/.

“Shackling and Separation: Motherhood in Prison | Journal of Ethics | American Medical Association.” n.d. AMA Journal of Ethics. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/shackling-and-separation-motherhood-prison/2013-09.

Talks, TedX. 2021. “What it is like to have a baby in prison | Jessica Kent | TEDxIndianaUniversity.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ucKFx427H5w.

Wang, Leah, and Bianca Schindeler. 2025. “Birth behind bars: Ten years of U.S. jail births covered in the news highlight horrific experiences and minimal data collection.” Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2025/07/01/jail_births_media_project/.

Wang, Leah, and Bianca Schindeler. 2025. “Birth behind bars: Ten years of U.S. jail births covered in the news highlight horrific experiences and minimal data collection.” Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2025/07/01/jail_births_media_project/.

Weichselbaum, Simone. 2021. “Hard Labor.” The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/04/15/hard-labor.

MUSIC CREDITS:

Beat Laboratory, Joint C. 2022. “Endorphin Release.” FMA. https://freemusicarchive.org/music/jcbl/tales-from-underground-vol1/endorphin-release/.

DrkAngl1. 2018. “Swan song – music box.wav.” Free Sound. https://freesound.org/people/DrkAngl1/sounds/416880/.

f-r-a-g-i-l-e. 2021. “Dancing Ducks Music Box.” Free Sound. https://freesound.org/people/f-r-a-g-i-l-e/sounds/613087/.

Nomagician. 2025. “Clean UI Sound.” Free Sound. https://freesound.org/people/Nomagician/sounds/833629/.

Setuniman. 2023. “Let’s go 1v25.” Free Sound. https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/715598/.

ZHRØ. 2023. “lonely music loop.wav.” Free Sound. https://freesound.org/people/ZHR%C3%98/sounds/676989/.

PHOTO CREDITS:

Barczyk, Hannah. “Hannah Barczyk.” Hannah Barczyk, Hannah Barczyk, https://hannabarczyk.com/projects. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Kent, Jessica. “My Daughter Was In Foster Care.” Medium, Medium, 26 May 2020, https://nymin89.medium.com/my-daughter-was-in-foster-care-e6ca571d89ff. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Kindelan, Katie. “Female lawmakers launch 1st Black Maternal Health Caucus.” Black Maternal Health Caucus, 10 April 2019, https://blackmaternalhealthcaucus-underwood.house.gov/media/in-the-news/female-lawmakers-launch-1st-black-maternal-health-caucus. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Weichselbaum, Simone. “Hard Labor A doula offers a little comfort for a birth behind bars.” The Marshall Project, The Marshall Project, 15 April 2015, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/04/15/hard-labor. Accessed 4 December 2025.