Rachel Davison

Both pro- and anti-abortion activists have referenced disability in their arguments and both ableist and disability justice rhetoric has been used by activists on both sides of the abortion divide. This podcast explores the ways in which the use of this rhetoric both aids and harms the disability community.

Transcript

MUSIC FADES IN THEN OUT

NARRATOR: There are many different facets of ableism, but a core idea is that having a disability is something that nobody wants, something that is to be shunned or avoided or overcome. Because disability carries so much emotional weight, it is often used as a point of rhetoric for and against issues—this thing causes a disability so it is bad, that thing cures a disability so it is good. However, the cure/cause distinction is much blurrier when it comes to abortion, such that both pro- and anti-abortion activists have referenced disability in their arguments and both ableist and disability justice rhetoric has been used by activists on both sides of the abortion divide. The issue of abortion in regards to disability is especially pressing given that the only way abortion can “cure” disabilities is by not allowing babies with them to be born in the first place.

NARRATOR: The principles of reproductive justice are the right to bodily autonomy, the right to have children, the right to not have children, and the right to raise children in healthy, safe environments. Reproductive justice is not about being pro-abortion or anti-abortion, it is about women having the right to be informed about, and access care for, their own bodies and children. This often intersects with disability justice, as much of ableism involves the assumption that disabled people cannot be trusted to make decisions about their own bodies, because their bodies are different from the norm. This is especially harmful for pregnant disabled women, whose lives are used in the battle over abortion without regard for their especially vulnerable position at the intersection of disability and pregnancy.

MUSIC FADES IN THEN OUT

NARRATOR: The two lines of rhetoric used in abortion debates tend to follow two of the principles of reproductive justice: the right to bodily autonomy and the right to not have children. Under the first principle, the mother has the right to bodily autonomy, and so she has the right to not sacrifice her own health for that of her fetus. This is the line of discourse which gives rise to arguments about late term abortion—once the baby is capable of surviving outside the womb, it is more difficult to make the argument that aborting it is preserving the mother’s bodily autonomy, because they can be separated without the death of the baby. Under the second principle, the mother has the right to choose not to raise the baby; the argument shifts from the morality of the baby’s death to the morality of the mother’s choice not to raise it. In terms of disability justice and the use of disability in abortion debate, the second principle is the one on which most arguments are founded, because the reason for abortion is the wish to avoid raising a disabled child.

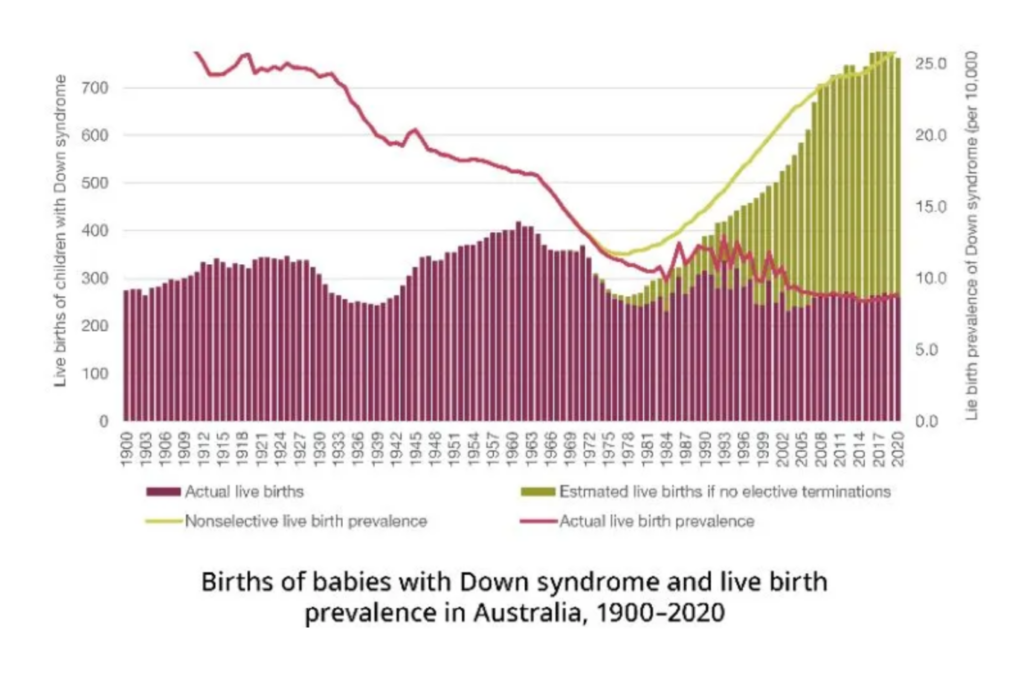

NARRATOR: In a world that considers disability to be a burden, many parents whose unborn child has been diagnosed with a disability choose to abort rather than carry the child to term—in Iceland, the rate of babies born with Down syndrome is thus very low due to widespread genetic screening. Even when parents do not wish to abort, oftentimes ableist healthcare providers will advise them that their child will have extremely poor quality of life and push them to abort. Given this situation, anti-abortion activists often reference abortion as something harmful to the disabled community, and use disability justice rhetoric to support their cause. This can be helpful to disability justice, because abortion is a hot-button topic right now, and any visibility the disability justice movement can get is important, since the majority of people would much rather just ignore its existence. However, since anti-abortion activists are just that, anti-abortion activists, and not disability justice advocates, they use disability for their cause, rather than truly fighting for disabled people, and so do not show the entire picture.

MUSIC FADES IN THEN OUT

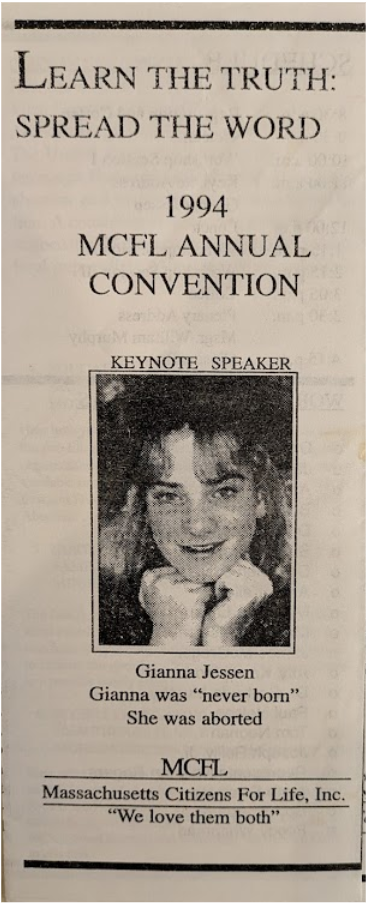

NARRATOR: Gianna Jessen is an anti-abortion activist with cerebral palsy who was born in the process of her mother getting a saline abortion and often uses the rhetoric of disability justice in her speeches. Her visibility and use of disability justice rhetoric is valuable, because disability justice is a concept that is remarkably ignored by many, but it is also misleading, because she ignores the broader context of reproductive rights for disabled people. For example, in one speech she says

JESSEN: “you continuously use the argument that if the baby is disabled we need to terminate the pregnancy, as if you can determine the value of someone’s life. Is my life less valuable because of my cerebral palsy? You have failed, in your arrogance and greed, to see one thing: it is often from the weakest among us that we learn wisdom.”

NARRATOR: This uses two points that disabled activists have been making for a long time—first, that disabled lives are not worth less than able ones, and being born disabled is not a status worthy of death, and second, that true justice must start with the most vulnerable. These are the principles of disability justice of “recognizing wholeness” and “leadership of the most impacted,” as laid out by the disability justice organisation Sins Invalid. However, though she uses this disability justice rhetoric, in the same speech Jessen later says

JESSEN: “We often hear that if Planned Parenthood were defunded, there would be a health crisis among women without the health services they provide. This is absolutely false! Pregnancy resource centers are located nationwide as an option for the woman in crisis. All of their services are free and confidential… There is access to vital exams for women, other than Planned Parenthood. We are not a nation without options.”

NARRATOR: This issue with what Jessen says here is that while, yes, the defunding of Planned Parenthood might not affect some people very much, it will affect others, especially those who are more vulnerable, like those who live in rural areas and disabled people. According to a report from the Congressional Budget Office, defunding Planned Parenthood would actually take away many people’s only option, leaving between one hundred and thirty thousand and six hundred and fifty thousand without a reproductive health resource close enough to access. Also, this statement ignores the very real situations in which pregnancy is disabling for the mother, or comes with life-threatening complications, or cannot be sustained while on medications essential for the mother, or the disabled mother, because of the inadequate levels of support for disabled people, knows that they will not be able to raise their child in a safe and healthy environment. Just because there are resource centers to support the pregnant woman does not mean that there are resources to support the disabled woman. When pro-abortion activists use disability justice rhetoric to make their points, this is what they focus on: the right of the disabled mother to make a choice about her own body.

NARRATOR: However, while abortion is an essential resource for disabled people to be able to use, it is also often a weapon wielded against them, by people who believe that disabled people cannot be parents and disabled children should not be born. Since many people do not view disabled people as being “fit” for or capable of parenting and do not think they can or should reproduce, sex education is not always taught to young people with disabilities, disabled mothers often have difficulty accessing maternal health care from ableist doctors, and many of the normal events that happen in the course of parenthood are not accessible. All of this adds up to a suggestion that disabled parents have an abortion, despite their ability and willingness to have the child.

NARRATOR: Abortion is not the only option, and it should never be the only option, but it is also not the only service offered by Planned Parenthood, and it also cannot always be discounted among the options for a pregnant person, because it is often a vital resource for a mother to be able to access. When anti-abortion activists speak of saving disabled babies, that is a worthy cause, but by disregarding the barriers they put in place for disabled mothers by closing essential clinics, they cannot truly be said to embody disability justice, only to have borrowed its rhetoric. Jessen is disabled, but she does not have all the same vulnerabilities as those who need the services she fights against. She can say

JESSEN: “Cerebral palsy, ladies and gentlemen, is a tremendous gift to me.”

NARRATOR: She can say this because although she is disabled, her disability is useful to her cause, not a burden to it. While disability pride is valuable, it is much more difficult for disabled people to maintain that pride when people insist on removing tools that support them in a society not built for them. Abortion bans do not affect everyone equally. When disabled people look for services, healthcare or otherwise, they are often assumed to be incapable of deciding their lives on their own terms, including whether or not to have and raise children. By advocating for abortion bans, Jessen becomes one of those people deciding for other disabled people rather than allowing them a choice.

NARRATOR: Also, despite their use of disabled babies as talking points against abortion, some anti-abortion activists also talk of “fetal abnormalities” as one of the very few valid reasons for abortion, thus ignoring the reality that not all “abnormalities” are fatal, and some are disabilities with which people live full and happy lives. This double standard sometimes causes pro- and anti- abortion activists to agree, in fighting for the right of an able parent to not have a disabled child. Though not everybody is capable of properly raising a disabled child, this loophole in some anti-abortion activists’ campaign for the rights of the unborn baby shows how entrenched ableism can be, even in movements that purport to be for disability justice.

MUSIC FADES IN THEN OUT

NARRATOR: Using disability justice rhetoric may somewhat aid the movement by spreading their message, but its use in the abortion debate twists that rhetoric for its own ends, rather than truly embodying disability justice. In an ableist world where it is assumed that disabled people don’t have the capacity to deserve many rights, including reproductive rights, but where they are nonetheless used as talking points in reproductive issues, it is important to allow disabled people to speak for themselves, and follow their lead in disability-centered rhetoric, rather than twisting it to serve one’s own ends.

MUSIC FADES IN THEN OUT

References

“10 Principles of Disability Justice.” Sins Invalid. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://sinsinvalid.org/10-principles-of-disability-justice/.

“Abortion and Disability: Towards an Intersectional Human Rights-Based Approach.” Women Enabled International, May 11, 2022. https://womenenabled.org/reports/abortion-and-disability/.

Adams, Char. “Disability Rights Groups Are Fighting for Abortion Access – and against Ableism.” NBC News, July 25, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/disability-rights-groups-are-fighting-abortion-access-ableism-rcna38703.

Camosy, Charles. “The Right to a Dead Baby? Abortion, Ableism, and the Question of Autonomy.” Public Discourse, April 22, 2022. https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2022/04/81840/.

Congressional Budget Office. Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate, H.R. 3134 Defund Planned Parenthood Act of 2015. Pdf. September 16, 2015. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/costestimate/hr3134.pdf

de Graaf, Gert; Skladzien, Ellen; Buckley, Frank; & Skotko, Brian G. (2022). Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in Australia and New Zealand. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 24(12), 2568–2577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2022.08.029

“Disability Justice.” We Testify. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://wetestify.org/abortion-explained-disability-justice.

Floyd, Kings. “Why Connecting Disability Justice and Reproductive Justice Matters.” The Century Foundation, May 24, 2024. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/why-connecting-disability-justice-and-reproductive-justice-matters/.

“Gianna Jessen | Abortion Survivor.” Accessed November 1, 2025. giannajessen.com.

Kolbi-Molinas, Alexa & Mizner, Susan. “The Offensive Hypocrisy of Banning Abortion for a down Syndrome Diagnosis: ACLU.” American Civil Liberties Union, July 19, 2023. https://www.aclu.org/news/disability-rights/the-offensive-hypocrisy-of-banning-abortion-for-a-down-syndrome-diagnosis. Stahl, Devan. “Reproductive Choice and Disability Stigma.” The Immanent Frame, August 14, 2020. https://tif.ssrc.org/2020/08/14/reproductive-choice-and-disability-stigma/.

Further Reading

Chris Kaposy. Choosing Down Syndrome : Ethics and New Prenatal Testing Technologies. The MIT Press, 2018. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=eb260d27-7554-309e-b9ff-bbba2c25b5f6

Bianchi, Andria, and Janet Vogt. Intellectual disabilities and autism: Ethics and practice. Cham: Springer, 2024. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-61565-8