Jiselle Ladriere

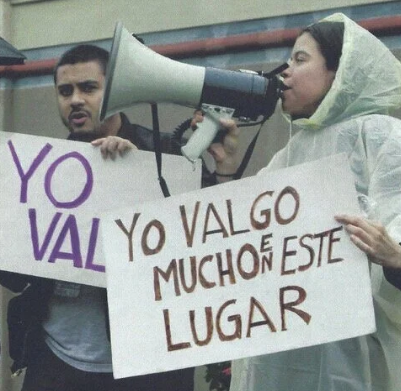

In this podcast, we will explore the complex realities of reproductive justice for Latina women in the United States and further examine how culture, Catholic faith, language barriers, and community/family expectations shape their access to healthcare and bodily autonomy. We look over the contradictions Latinas navigate such as practicing their faith while also resisting church teachings through contraception use, or needing reproductive care in systems that lack care that can help them.

Transcript – Mi Cuerpo, Mi Voz

Hello everyone! My name is Jiselle and I am here to explore something deeply personal and deeply political: the struggles and complexities for reproductive justice among Latina women in the United States.

For many Latina women, making decisions about their bodies is not just a private matter. It is also intertwined with faith, cultural expectations and language. It is something that many Latinas, including myself, aren’t always sure when or where we’re “allowed” to talk about.

The question that we will be asking ourselves today is:

What does it mean to navigate healthcare, reproductive rights, and bodily autonomy while also juggling the pressures from culture, faith, language, and community expectations?

As a Latina, I have grown up seeing how complicated this can be. I have seen women fear being judged as “bad Catholics,” others unable to speak up due to language barriers, and many caught between respecting cultural traditions and trying to assert their own autonomy.

I want to acknowledge that as a Latina raised around Catholic influences and communities, I’ve been in rooms where even mentioning abortion gets you looked at like you’ve just confessed to a crime. However, I have also been in spaces where Latina women are open, thoughtful, and honest about their reproductive needs. In this episode, I will be exploring the barriers Latinas face, the choices they make, and how they rely on cultural pride, family, and community networks to remain strong and resilient.

Reports from the National Partnership for Women & Families show that nearly 6.5 million Latinas live in states with abortion bans or strong restrictions such as Texas, Florida and my home state, Arizona, meaning they are disproportionately harmed. And paired with the fact that Latinas have higher rates of jobs without paid time off, traveling for out-of-state care becomes almost impossible.

By looking at these pieces of information, we can see that “choice” doesn’t mean much if you cannot access the system in your own language, or if the nearest clinic is hundreds of miles away.

The role of religion, especially Catholicism, is huge when talking about Latinas’ access to bodily autonomy. In Borderlands/La Frontera, Gloria Anzaldua writes about living in a “constant state of transition,” negotiating conflicting identities and expectations. Many Latina women experience reproductive decision-making in that same sort of in-between lens: a spiritual borderland where faith, cultural and family loyalty, and bodily autonomy collide.

Anzaldua writes that Latina women live within contradictory messages because on one side, Catholicism teaches obedience, purity, and motherhood as a gift. On the other, modern life demands autonomy, consent, and control over one’s body. Most of the barriers that Latinas face are rooted in their upbringings. A lot of Latinas grow up hearing:

- “Good women don’t have sex before marriage”

- “Birth control is sinful”

- “Abortion is murder”

However, these women are trying to hold jobs, finish school, support their families, and plan their futures. Oftentimes, reproductive decisions are not simply made. They become a negotiation, involving not only healthcare systems, but also one’s own family and community.

An important fact that the NLIRH fact sheet makes very clear is that 96% of sexually active Catholic Latinas use contraception that the church forbids and 90% of married Catholic Latinas rely on modern birth control. As we can see, Latinas are already making decisions that prioritize their well-being, even if it means resisting cultural or religious expectations.

However, this does not mean that they are rejecting Catholicism – they’re adapting it. They engage in what Anzaldua calls the “new mestiza consciousness”, forming a blended identity in which both reproductive autonomy and faith can coexist.

Another barrier that Latinas face when accessing reproductive healthcare is language. The League of Women Voters describes language services as one of the central barriers that Latinas come across when seeking reproductive care. In many states, clinics lack Spanish-speaking staff, trained interpreters, or culturally competent communication.

The lack of these necessities may lead to misunderstandings about medical care, incorrect dosing, uninformed consent, and mistrust of providers. Something as simple as scheduling an appointment or understanding contraception options becomes very difficult for patients if providers don’t offer these services. Immigrant Latinas also report avoiding medical care because they fear immigration enforcement, even if they are citizens.

The 2025 Springer study on Latina Immigrants article argues that language differences can “magnify perceived risk,” making Latina women more fearful and hesitant to seek contraception, abortion, or simply gynecological care. According to NLIRH, nearly one in four Latina immigrants reports avoiding healthcare because of these language and communication challenges.

Language justice, then, is inseparable from reproductive justice. Clinics that have English only paperwork that require fluent literacy in English and English speaking only healthcare providers are complete systemic barriers.

I turned to Loretta Ross and her co-authors in Undivided Rights to search for the explanation on how Latina activists expanded reproductive rights beyond the narrow pro-choice frame used in mainstream feminism.

For them, reproductive justice includes: language access, economic stability, immigration safety, access to childcare, and the right to raise children in safe environments.

Ross describes Latina organizers viewing reproductive autonomy as collective rather than individual. It is about ensuring not only the right to have children, but also the right to raise children without violence, poverty, or state surveillance. The book emphasizes that reproductive justice for Latinas must be holistic and intersectional, which further highlights how Latinas must navigate far more than simply “choice.”

So, what do we want reproductive justice to ultimately look like for Latinas?

- Access that respects language and cultural identity

- Healthcare that understands and honors faith and personal belief

- Community-based support

Reproductive justice for Latinas is not just about “choice,” it’s about access, community, and power. Understanding the barriers that Latinas face when accessing reproductive care means understanding that resilience is not optional for them, it is a survival strategy.

So, when asking ourselves what it means to navigate healthcare, reproductive rights, and bodily autonomy while struggling with the external pressures from culture, faith, language we see that the systems around Latinas often fail to support them. We realize that the path toward bodily autonomy is never direct – it is made up of confusion, contradictions, and compromises that demand resilience and adaptation.