Abigail Moore

This podcast explores the United States’ long history of debate over sex education’s place in schools and in the lives of adolescents. What began as a taboo subject in the Victorian era transformed throughout the twentieth century into an ongoing discussion about appropriate curricula and what students should learn. Though sex education has come a long way, debate continues today over what these courses should include and who should shape them.

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to Victorian Silence and Modern Debate: A History of Sex Education in America. Today we will be discussing the country’s long and tumultuous history with sex education, and the effect this has had on curriculums today.

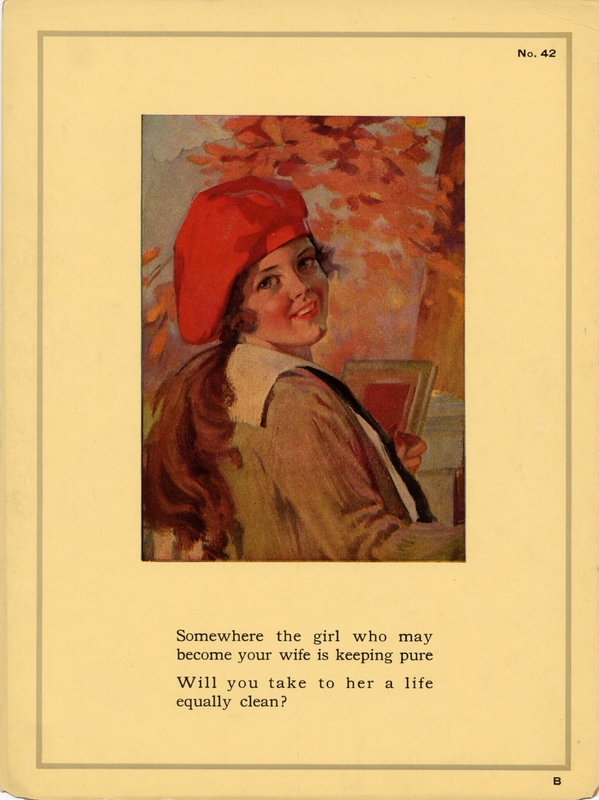

We begin our historical journey in the late 1800s, where most unmarried women, even those with college degrees, know very little about “premarital” or “marital” relations. This was due to a common belief at the time that if women were to know about sex, that they would have “unchaste thoughts” or “lustful impulses” to quote the book Touchy Subject: The History and Philosophy of Sex Education by Lauren Bialystok and Lisa M.F. Andersen. This was mostly a value pushed upon middle class women, who needed to remain virtuous and pure in order to seem more desirable to their future husbands. In the 1890s, however, a Dr. Clelia Duel Mosher began a survey that altered the way we now view these women. The Mosher survey asked Victorian wives about their knowledge of sex, and revealed that many of the women understood sex as a form of pleasure, not just a means for reproduction, but it also emphasized that these wives had little to no knowledge of sex before they were married. It is possible that some of the women simply feigned ignorance due to societal pressures, but it is also likely that they really knew so little due to censorship. Books marketed towards women were very vague when discussing sexual topics, and those that were more explicit were quickly banned. Additionally, materials deemed ‘obscene’ were criminalized and banned from the mail. When young women went to their parents with questions, their curiosities were dismissed as being inappropriate or answered in confusing and inexplicit terms. At this time, parents believed that it was the husband’s duty to teach his wife about sex because a woman only needed to know about it in terms of what it would entail with her husband specifically, so that she would remain faithful. In order to teach their wives, men needed to have knowledge of sex, so this information was more available to them than it was to women. Books specifically targeted towards men were more explicit than the books for women, and men also learned from parents, friends, and social places such as saloons that promoted promiscuity and prostitution.

In the early 1900s two groups arose who were concerned about the lack of sexual education that women were receiving: social hygienists and social purity reformers. The former group mainly consisted of physicians who recognized the need for more education in order to prevent venereal diseases. Social purity reformers also favored sex education because it allowed them to stress abstinence and other purist ideals. In the 1910s, compulsory education and attendance policies became more widespread throughout the United States, meaning that adolescents were increasingly more likely to be found in schools. Both social hygienists and social purity reformers realized this opportunity and worked together to push for sexual education curriculums to be added to schools. They determined that early high school was the best time to teach sex education, mainly because the content could most easily fit into the biology curriculum. The government funded sex education programs in over 40 schools, colleges, and universities to help prevent the high rates of venereal diseases found in World War I army recruits. In Chicago, the superintendent arranged for a series of lectures on sex education that were very well received by students, especially among adolescent women who were glad to obtain the answers to questions other sources had failed to address. In other school districts, similar programs received equally positive feedback from students, though they were not without problems. Many Conservative parents, particularly Catholics, saw the curriculum as obscene and demanded its removal. Several teachers also felt unable to teach sex education due to their own religious beliefs or their lack of personal experience or training. Those that could teach were very vital to these new programs, but even some of those teachers withheld information, believing their students to be too young or fearing that they would lose their jobs. In the end, what was taught in these early programs was overly technical and boring which may have been intended to dissuade students from partaking in sexual activities, but it also prevented many from being able to understand the material.

As we moved into the 1920s, a new form of sexual education arose that was more akin to the health courses of today. This curriculum, known as Family Life Education mainly focused on family transition and happy marriages. Increasing access to contraception and abortions led to decreased rates of STIs and teen pregnancies, so those topics were not emphasized as much as they had been previously. Educators were also scared of complaints, so they significantly reduced the amount of sex ed topics included in the course. These measures to restrict Family Life Education courses were not successful at avoiding backlash. In a time of growing apprehension about the threat of Communism, parents feared that open-ended exercises in these classes would cause their children to think for themselves and disobey their parents, thus being vulnerable to Communist influences. These concerns led to even more restriction, until sex education was virtually absent from Family Life curriculums.

In the 1980s, however, the need for sex education became more urgent due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In 1981, the Adolescent Family Life Act funded education programs that supported abstinence until marriage and favored adoption over abortion. Other topics such as contraception, STIs, and homosexuality were not taught and were even condemned in some cases. Many teenagers realized the problems that this censorship caused, so they took matters into their own hands. A lot of adolescents were involved in AIDS hotlines and clinics, where they were taught about risks and measures to reduce those risks, and they brought this knowledge back to school where they were able to inform their peers. This was a method that was hard to stop because you can’t remove students from schools.

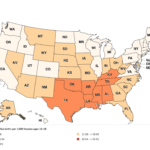

By the end of the twentieth century, we saw many shifts in how sexual education was taught and received throughout the country. These differences are certainly reflected in the varying curriculums and issues we know today. To really understand how this history of censorship and competing moral values continues into the present, it is helpful to look at two states that have taken very different approaches: Texas and California. Every year, Sex Ed for Social Change grades each state on their sex ed curriculum. In 2025, Texas received a C minus overall, with a D for their sex ed requirement, and a C minus for content. Although this is not the lowest score possible and is an improvement from previous years, it still leaves a lot to be desired. In Texas, health is an optional elective for high school students, and if schools chose to teach sex education, they must emphasize abstinence over anything else. The Sex Education Collaborative, describes this type of curriculum as “abstinence-plus” because it does include some instruction on anatomy, contraception, and STI prevention, but abstinence is the main focus. If schools also wish to mention homosexuality, they must condemn it as a criminal offense, despite the fact that it is not. This practice echoes the country’s history of sex education censorship and illustrates how limited sex education is in Texas, regardless of the many reliable sources that cite Comprehensive Sex Education programs as gold standard for keeping students appropriately informed and for preventing STIs and teen pregnancies. In fact, according to the CDC, in 2023, Texas had a teen birth rate of 19.4 births per 1000 females aged 15-19. The World Population Review partially attributes these statistics to a lack of sex education and the prevalence of abstinence-only programs. In California in 2023, the teen birth rate was only 9.1 births per 1000 females aged 15-19. This is certainly an improvement from Texas, and is likely due to the comprehensiveness of California’s sex education program. Sex Ed for Social Change gave the state an A minus overall, with an A for sex ed requirement and a B+ for sex ed content. In California, schools are required to teach comprehensive sex education that includes instruction on abstinence and is medically accurate. Schools are also required to make the course inclusive to students of all sexual orientations and gender identities. For instance, when providing examples of different relationships, teachers are required to include same-sex couples. This ensures that all students are given instruction that is applicable to their lives. Although this curriculum is far from perfect, (it does not include information on consent, for example) it is certainly a step in the right direction compared to more conservative states. The stark contrast between these two states reflects not only the current political environment, but also the historical tension between abstinence-focused education and comprehensive sex education.

We have come a long way from the extreme censorship of the early twentieth century, but many states still have much more progress to make before sex education can truly serve its main purpose: to prepare adolescents for healthy and happy relationships, free from STIs and unwanted pregnancies. Conservative states, like Texas, could greatly benefit from the comprehensive sex education curriculums utilized in more liberal states including California. We have seen how much students of the past benefitted from sex education, and how many efforts were necessary in order to bring about change. It seems that programs are most widely accepted when they offer a compromise between groups who favor abstinence education and those who favor discussion of a wider range of topics, such as the earlier alliance between social hygienists and social purity reformers. As sex education continues to evolve, policy makers should reflect on the important lessons from the past that illustrate how vital sex education is to adolescents and how the more inclusive the curriculum is, the more positive its effects will be.

References

De Kok, Sara, Janine Utell, and Molly Wolf. “Wolfgram Subject Guides: Modern Sexual Cultures: Early 20th-Century Pamphlets.” Modern Sexual Cultures: Early 20th-Century Pamphlets – Wolfgram Subject Guides at Widener University. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://widener.libguides.com/MSC.

Pure girl is waiting somewhere. 1922. Photograph. https://gallery.lib.umn.edu/items/show/236.

“SIECUS State Profiles.” SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, August 8, 2025. https://siecus.org/siecus-state-profiles/.

“Teen Births.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/state-stats/births/teen-births.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fnchs%2Fpressroom%2Fsosmap%2Fteen-births%2Fteenbirths.htm.

“Teen Pregnancy Rates by State 2025.” World Population Review, November 21, 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/teen-pregnancy-rates-by-state.

“Texas.” Sex Education Collaborative. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://sexeducationcollaborative.org/states/texas.

Further Reading

“Sex Education and HIV Education.” Guttmacher Institute, September 16, 2025. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education.