Immi

This episode of “Dykes on Mics” challenges the persistent assumption that pregnancy and reproductive healthcare belong exclusively to cis-women. By centering trans*, nonbinary, and gender-expansive (TNBGE) people, it exposes how medical systems reproduce harm through misgendering, deadnames, gender-essentialist language, and a lack of provider knowledge.

Transcript: Unlinking Womanhood and Pregnancy

{Music plays}

{Music fades out}

“Are you on birth control?”, “Do your boobs also get sore during your period?”, “You’ll be such a good mother”, “Is it going to be a girl or a boy?” – These are the kinds of questions and statements many people hear about reproductive health and while they’re not purposefully harmful, they do assume gender, sexuality and what it means to create a family.

Hi everyone and welcome back to „Dykes on Mics!”. I am your host, Immi, a non-binary lesbian, a dyke on a mic, and today we’ll we be taking a closer look on queering reproductive justice. More specifically, I’ll be focusing on how medical settings treat transgender, nonbinary, and other gender-expansive people, which are referred to as TNBGE in this podcast.

Before we dive deeper, let’s briefly discuss what reproductive justice actually means. The SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective defines reproductive justice as the human right to have children, to not have children, to parent children in safe and healthy environments and to maintain bodily and sexual autonomy and gender freedom for every human being.

Although conversations about reproductive justice in the U.S. and back home in Germany have become more public, they still too often assume that everyone who gives birth, or seeks reproductive healthcare, is a cis-woman. And that assumption doesn’t just show up in public discourse, it’s built into the medical system itself. As a result, TNBGE people are routinely erased. This directly translates into barriers of care, higher rates of medical trauma, and worsened medical outcomes.

Before we get into pregnancy, I want to broaden the perspective. Reproductive justice doesn’t begin with wanting a child; it begins with how we’re treated in everyday healthcare. So first, I’m going to look at what routine reproductive care actually looks like for TNBGE people, including my own experiences. Then I’ll focus on reproduction itself: what it means to queer the whole idea of who gets to get pregnant, stay pregnant, end a pregnancy, or build a family.

When I used the binder library of the Smith College’s Schacht Center some weeks ago, I realized for the first time what it feels like to receive gender-sensitive care. It made me aware of how often medical settings do the opposite. In my experience, when going to the Gynecologist, I’ve been asked to remove my t-shirt so that the doctor could examine my breasts even though the same tissue is referred to as the chest in gender-affirming contexts. Misgendering, deadnaming, and gender-essentialist language aren’t small mistakes. They can generate or intensify discomfort, stress, shame, gender dysphoria, anxiety, and alienation; ultimately making medical spaces feel unsafe or even inaccessible. Especially in a space as vulnerable as a gynecologist, where your naked body is exposed, where you share intimate concerns, and where you would rely on the provider’s expertise, that harm hits particularly deep and might lead to medical trauma. And it’s devastating, because this isn’t only about awkward everyday comments, it’s the medical system itself making people feel unsafe. Experiencing care that didn’t reproduce these harms showed me just how radically different health care could feel if providers stopped assuming one’s gender identity, sexuality, and body.

Research backs this up: TNBGE people experience disproportionately high rates of trauma, including medical trauma, and these experiences directly shape their reproductive health as trauma is for instance linked to worse pregnancy and postpartum outcomes as well as higher risks during birth. In fact, a 2024 study by Stroumsa, Raja, and Russell found that half of all TNBGE patients had to teach their own providers how to care for them. Thus, we need a structural change towards trauma-informed, gender-affirming healthcare that ensures emotional and physical safety as medical environments too often compound harm through gender-essentialist language, invalidating visuals, and a lack of provider knowledge.

Now, let’s shift the focus to the right to have or not have a child, and to parent children in safe and healthy environments. For TNBGE people, the journey of becoming a parent is often exclusionary and can trigger dysphoria. There is no one-size-fits-all experience: some people feel affirmed by visibly pregnant bodies but face increased hostility if they present more masculine, while others prioritize safety over visibility yet at the cost of potentially experiencing dysphoria. Hormone decisions, such as testosterone use, further complicate care, highlighting the need for individualized, gender-affirming support.

However, hospitals and educational materials, but also everyday examples mostly show images of feminine pregnant bodies and use terms like “mother” which can make TNBGE people feel erased or excluded. Moreover, the whole capitalist industry behind gendered pregnancy gifts like gender reveal parties’ supplies reinforce this alienating experience.

Queering reproductive justice thus also means accessing gender-affirming medical care, a safe navigation of pregnancy, and the ability to raise children in affirming environments without being limited by cis-heteronormative assumptions and systemic barriers.

To be honest, I’m already scared about what it might feel like to have a child. I refuse the idea that I shouldn’t want to be pregnant just because pregnant bodies often look so different from mine. At the same time, I can also imagine feeling intense dysphoria navigating pregnancy in a system that rarely affirms TNBGE identities. The tension between wanting to experience pregnancy and confronting a medical and cultural environment that may misgender or erase you is exactly why reproductive justice for TNBGE people must include not only the right to have or not have children, but also access to gender-affirming, individualized care that supports bodily autonomy throughout pregnancy.

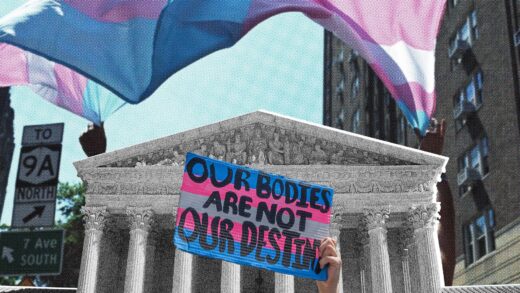

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about how healthcare should look trauma-informed and gender-affirming. However, we can’t ignore the political reality shaping these conversations right now. In the U.S., the current administration has moved to restrict the legal recognition of TNBGE people, for example, by asking the Supreme Court to allow a ban on accurate gender markers on passports and threatening to defund hospitals that provide gender-affirming care to youth.

Back home in Germany, the far-right AfD uses similar rhetoric and portrays gender diversity as a societal threat. Their party program denies the existence of more than two genders, and frames gender diversity as ideology, manipulation, and early sexualization.

Hearing this language today has a disturbing historical echo. In 1933, the Nazis destroyed the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin, the world’s first Western institute dedicated to studying sexuality and gender diversity, founded by the Jewish German physician Magnus Hirschfeld, which offered early forms of gender-affirming care; and that’s exactly why it was targeted.

However, while Western history often frames this as the “first” institute of its kind, gender-expansive identities have existed and been documented for thousands of years across the globe, long before Western science attempted to categorize them, like, for example, Two-Spirit roles in Indigenous North American nations or complex gender systems in parts of Africa, as described in Male Daughters, Female Husbands. Gender diversity is not new, but settler colonialism has actively suppressed, erased, and pathologized these longstanding understandings of gender.

Today’s political attacks, in the U.S., Germany, and beyond, shape the conditions in which marginalized identities access healthcare and build families. And that’s exactly why we have to push back. Structural change in medicine requires social change: implementing gender-sensitive language in our daily lives might seem small, but it’s one thing these political movements cannot legislate out of us. It’s a form of resistance, of keeping each other safe, and insisting on our existence – thank you so much for listening to this episode!

{Music fades in}

{Music plays}

References

Al Jazeera. “Trump Seeks Enforcement of Transgender and Non-Binary Passport Policy.” September 20, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/20/trump-seeks-enforcement-of-transgender-and-non-binary-passport-policy

Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2025: „Zeit für Deutschland.“ Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.afd.de/

Amadiume, Ifi. Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society. Zed Books, 1987.

Arvin, Maile, Tuck, Eve, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy,” Feminist Formations 25, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006

Bond‑Theriault, Candace. Queering Reproductive Justice: An Invitation. Stanford University Press, 2024.

ConexaoCabeca. Pregnant, Mom, Photograph, Pixabay. Accessed December 1, 2025, https://pixabay.com/photos/pregnant-mom-pregnancy-2763931/

Craver, Aiden. A group of people, holding signs and wearing masks. 2022, Photograph, Unsplash. Accessed December 1, 2025, https://unsplash.com/photos/joz_6QRCxds

Ingenious0range. A sign, that shows, that correct pronoun usage saves lives. 2023, Photograph, Unsplash. Accessed December 1, 2025, https://unsplash.com/photos/2nfBgN5sL6k

Kukura, Elizabeth. “Reconceiving Reproductive Health Systems: Caring for Trans, Nonbinary, and Gender-Expansive People During Pregnancy and Childbirth.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 50 (Fall 2022): 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/jme.2022.88

Langdon, Andrew. “Aioli.” Dance & Electronic, November 2019. YouTube Audio Library, 00:01:59. https://studio.youtube.com/channel/UCKO9DLOVM3bcxyr2TRoYtlA/music

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e. V. Photograph of a costume party at the Institute for Sexual Research (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft), date unknown, depicting Magnus Hirschfeld (right, wearing glasses) holding hands with Karl Giese. 2022, Photograph, The Public Domain Review. Accessed December 1, 2025, https://publicdomainreview.org/search/?q=magnus+hirschfeld

NPR. “Trump Looks to Ban Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender and Nonbinary People via Medicare, Medicaid.” October 30, 2025. https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2025/10/30/nx-s1-5588655/transgender-trump-medicare-medicaid-gender-affirming-care

Patton‑Imani, Sandra. Queering Family Trees: Race, Reproductive Justice, and Lesbian Motherhood. NYU Press, 2020.

Ross, Loretta J., and Rickie Solinger. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. University of California Press, 2017.

Ross, Loretta J. “Reproductive Justice as Intersectional Feminist Activism.” Souls 19, no. 3 (2017): 286–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2017.1389634

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “Kwe as Resurgent Method.” In As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. “Reproductive Justice.” Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice

Stroumsa, Daphna, Raja, Nicholas S., and Colin B. Russell. “Trauma-Informed Reproductive Care for Transgender and Nonbinary People.” Reproduction 168, no. 6 (December 1, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-24-0054

The White House. “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” January 20, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/defending-women-from-gender-ideology-extremism-and-restoring-biological-truth-to-the-federal-government

The White House. “Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation.” January 28, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/protecting-children-from-chemical-and-surgical-mutilation/

For further readings

Spira, Tamara Lea. Queering Families: Reproductive Justice in Precarious Times. University of California Press, 2025.