Charlotte Engrav

(Caption for featured image: a collage of pieces of queer Filipino history, including photos from pride parades, backstage at transgender beauty pageants, the first transgender government official, and older photos of gay men.)

Audio Transcript

Charlotte: As a queer mixed Filipino-American, growing up in a second-generation household, my relationship with the cultures I’m tied to has always felt a bit odd. I grew up in Seattle, WA – a city with a high Asian population. It wasn’t hard to walk down the street and see a variety of people who looked like me – in one way or another. Seattle also has a large queer population. Over half a million people – far over half of the city’s population – are estimated to show up to pride celebrations every year. Arriving here at Smith, I’ve felt a huge sense of queer representation. And nearly none of Filipino representation.

C: I spoke with two of my other queer family members, to compare the queer Filipino experience through the generations.

(MUSIC, FADES OUT)

C: I first spoke with my uncle.

Nono: My name is Cesar Conde.

C: We call him Uncle Nono.

N: I consider myself as a Filipino American queer artist of color.

C: He’s my mom’s half-brother, and lived the beginning of his life in the Philippines. He described it as a strictly Catholic country that feels like it’s trying to be accepting.

N: If they’re lesbians or trans, it’s okay as long as they’re not a part of your family. So in my family, there’s a denial more specifically from the grandparents… you just turned a blind eye.

C: This Catholicism has deep roots in Filipino history, specifically its in colonization. When Spanish conquistadores arrived, one of the first moves was to convert thousands from indigenous religions to the Catholic way. In doing so, economic and social systems were forever changed. For hundreds of years since, Catholicism has forced the hundreds of spiritually queer folks into marginalization and silence. Filipino Scholar Brenda Rodriguez Alegre wrote that “Growing up in the Philippines had this silent and unlabeled experience whereby we got trained to discern and identify and who are queer among us. And it is not probably because we live in a very repressed society.” From earliest stages of history recorded on a western scale, queer Filipinos have not had the autonomy to live life as their full selves. Uncle Nono said the same thing.

N: Growing up in the Philippines we were always surrounded by queerness although we just didn’t talk about it… I did not come out until I was 20 years old.

C: While he was at a turning point in his life, studying in Spain and discovering a more open queer community, back home in America looked different.

N: I came out at a time during the AIDS crisis where you not only have a stigma of AIDS in the 80s. And then you also have a government which did not even mention aids as gay men were dying.

C: Representation on TV was bleak too. White queerness was just starting to be accepted by greater society, but Uncle Nono found that:

N: Most of the images were very different from what I have – who I am. There were no images of Filipino or Asian queers on television. It wasn’t until Will and Grace game out that pop culture started opening up and embracing gayness… other than that it is very isolative.”

C: In 2022, things have changed. He’s found more community that straddles queer and Asian identity in a positive, celebratory way:

N: We used to have a Miss Universe pageant. And it was a friendly Asian American queers doing Miss Universe, in their own creative interpretation that was so much fun, and very supportive, and just full of celebration.”

C: Miss Philippines winning Miss Universe in 2015 was a big deal for that community too. Here’s there reaction:

(AUDIO OF NONO AND HIS FRIENDS CHEERING)

C: This celebration also extends to the younger queer community. He ended our interview reflecting on the future. He wants to be a part of the movement towards a healthier, happier world.

N: It’s wonderful to see 17 year old 18 year olds, 16 year olds finding out who they are and being celebrated. Hopefully the suicide rates on people questioning their sexuality has gone down because we are here for them.

(MUSIC BEGINS)

C: One youth he’s supported through their journey is my sibling.

(MUSIC FADES UNDER RAE)

Rae: My name is Raelin Engrav, I use the pronouns he and they… I identify as agender, um Filipino, bisexual.

C: I started our conversation reflecting on their experience as a Filipino-American, and how it differs from Uncle Nono’s. We’re a second-generation family. The children in our household didn’t grow up speaking Tagalog. Sometimes we’d head next door, where our Lola lives for a hot breakfast or dinner. She’d speak a mixture of English and Tagalog to us and our mom, and much of it would wash over our heads. But for Rae:

R: There are still some words that I feel a very deep connection to – be it how Lola would tell us to you know keep eating, or we’d have to tell her in Tagalog when we were full.

C: When they came out as Agender, Uncle Nono gave him a nickname – a tradition in some Filipino circles.

R: In English, there is sort of a push for the word Nibling. And we kind of both were laughing at how it’s not like the best word and doesn’t feel very personal. And so instead he often refers to me using the Filipino words for like the equivalent of niece and nephew, as in Tagalog it’s a more gender-neutral term.

C: Tagalog serves as an archival view into the precolonial Philippines. The word Rae mentioned isn’t the only genderless identifier – there is no word for sister or brother either, just sibling. Rae’s experience with the queer community is different from Nono’s as well. They lived in a much more accepting world, built on the back of a very supportive family. For him, coming out as bisexual didn’t feel like a big deal:

R: I knew I was bisexual before I knew the term bisexual because I knew I liked girls, I knew I liked boys. I knew I liked people regardless of that. It was cool to learn a word and have a language to use to describe myself.

C: Their agender identity is where the struggle came into play. It’s a more contemporary label, and less people are aware of it. It also came with the crushing factor of gender dysphoria. Rae told me they work through it by remembering the other side – the gender euphoria and the enlightenment that comes with it.

R: I think I also feel more deeply related to my agender identity in a way because I fought and struggled for it.

C: The two identities overlap most for him in the way that he interprets gender expression. Sometimes, the label ‘agender’ comes with the expectation of a rejection of one’s assigned gender at birth – and in a western gender binary, that works. But Rae and other queer Filipino scholars like Alegre aren’t interested in that binary. As reflected in Tagalog, pre-colonial Philippines saw a very different spectrum of gender. On a very spiritual level, Babaylans were the Filipino equivalent to the two-spirit identity: “acknowledging the power of not just one but two aspects of spirituality in their being, that which could be called the masculine and the other the feminine,” (Alegre). Rae challenges this binary every day:

R: The view of androgyny is often tied to whiteness and often tied to maleness and those are things that I don’t necessarily want to appear as. I think that the identity that I am perusing is more feminine and is more tied to femininity in that I find femininity a lot more appealing than masculinity. And yet, there’s sort of a balance between those things that I’m looking for that is inherently opposed of that white image of what androgyny can look like.

C: In my discussion with family, this need for personal decolonization has stuck with me. In my research, I have woven a thread of connection through hundreds of years of ancestry, and at its root is a sense of collective survival and joy. Living as a mixed-race child of immigrants can be confusing, and nothing has been more liberating than feeling seen and accepted by history, and eventually reclaiming what was lost.

Works and Images Referenced/Cited

Alegre, Brenda Rodriguez. “From Asog to Bakla to Transpinay: Weaving a Complex History of Transness and Decolonizing the Future,” Alon: Journal for Filipinx American and Diasporic Studies. Vol 2, No. 1 (March 2022), pp. 51-64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48656850#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed December 2022.

Conde, Cesar. 2022. Interview by author. Zoom. December 5, 2022. Accessed December 2022.

Engrav, Raelin. 2022. Interview by author. Zoom. December 5, 2022. Accessed December 2022.

Figure 1, Engrav, Raelin. “Drawing 1,” Colored Pencil, Seattle, Washington. 2022. Accessed December 2022.

Figure 2, Engrav, Raelin. “Drawing 2,” Colored Pencil, Seattle, Washington. 2022. Accessed December 2022.

Figure 3, “Portrait of Cesar Conde.” Voyage Chicago. http://voyagechicago.com/interview/check-cesar-condes-artwork/. Accessed December 2022.

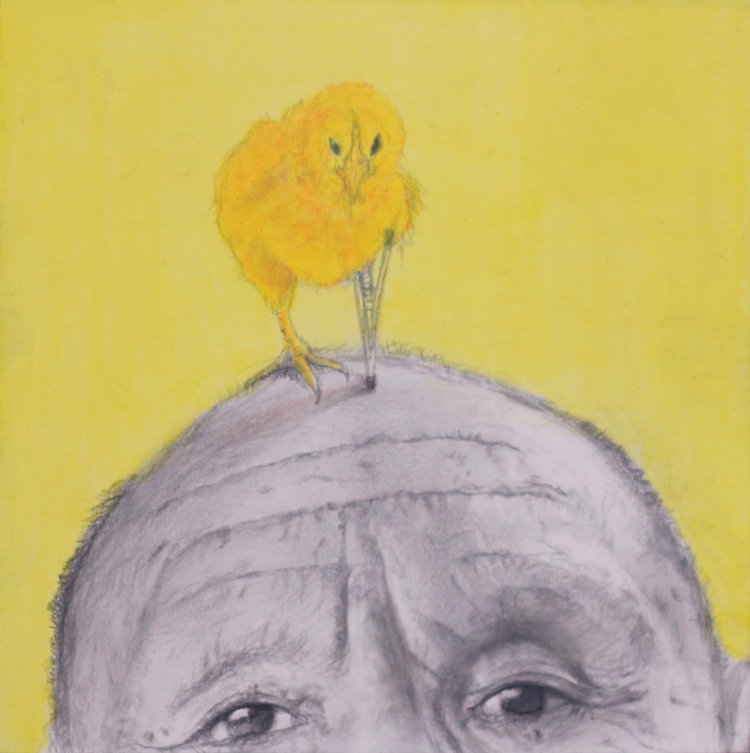

Figure 4, Conde, Cesar. “Chick with a Broken Wing – a Self Portrait,” Charcoal, graphite, and acrylic. Chicago, Illinois. 2018. https://www.cesarcondeart.com/of-human-survival. Accessed December 2022.

Garcia, J. Neil C. “Lolo Pulong,” Budhi: a Journal of Ideas and Culture. 2000. https://ajol.ateneo.edu/budhi/articles/214/2399/read. Accessed December 2022.

Melvin, Joshua. “A Manille, des seniors gays se mettent en drag pour survivre,” Yahoo News. July 22 2018. https://fr.news.yahoo.com/manille-seniors-gays-mettent-drag-survivre-081621725.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYmluZy5jb20v&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAD5GyRWe9hEZ8FHWC_oEHhUnQ3yjaiwcc10yozAIRtdXdwUPXdhycffQYFiWqQKyUGniuJjFExGS7EJoR-d1v_g8jpTfGDrmatPFT62-Q5Q5B3pXuyJ5kXUEL5GXiwr4CmUy9tsCUfm59I3uSMxjMPrR7FKz6Z9U8stQn3CPOwf1. Accessed December 2022.

Palatino, Mong. “Remembering Asia’s first Pride march in Manila,” Global Voices. June 11 2021. https://globalvoices.org/2021/06/11/remembering-asias-first-pride-march-in-manila/. Accessed December 2022.

Patria, Kim Arveen. “A first, Philippines stand against LGBT hate at UN,” Yahoo News. September 30, 2014. https://ph.news.yahoo.com/blogs/out-and-proud/a-first–philippines-stand-against-lgbt-hate-at-un-035634118.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYmluZy5jb20v&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAD5GyRWe9hEZ8FHWC_oEHhUnQ3yjaiwcc10yozAIRtdXdwUPXdhycffQYFiWqQKyUGniuJjFExGS7EJoR-d1v_g8jpTfGDrmatPFT62-Q5Q5B3pXuyJ5kXUEL5GXiwr4CmUy9tsCUfm59I3uSMxjMPrR7FKz6Z9U8stQn3CPOwf1. Accessed December 2022.

Reyes, Hannah. “Portrait of Angel Cabaluna,” The Seattle Times. 2018. https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/a-transgender-paradox-and-platform-in-the-philippines/. Accessed December 2022.

Sawatzky, Robert. “Philippines elects first transgender woman to congress,” CNN. May 10, 2016. https://www.cnn.com/2016/05/10/asia/philippines-transgender-geraldine-roman/index.html. Accessed December 2022.