Tenzin Seldon

In a contemporary ethical landscape where debates about abortion are largely shaped by Western legal discourse and Judeo-Christian moral frameworks, it becomes crucial to consider alternative perspectives. Buddhist traditions offer a markedly different narrative—one grounded not in rights or divine commandments, but in notions of interdependence, nonviolence, karmic continuity, and the rarity of human life. Attending to this Buddhist ethical framework allows for a more nuanced and globally informed understanding of reproductive ethics.

Transcript

Hello guys, welcome to “Breaking the Silence.” My name is Tenzin Seldon, and in this podcast, we will explore abortion from a Buddhist perspective. We had enough of the Western view on abortion; let’s go to the East!

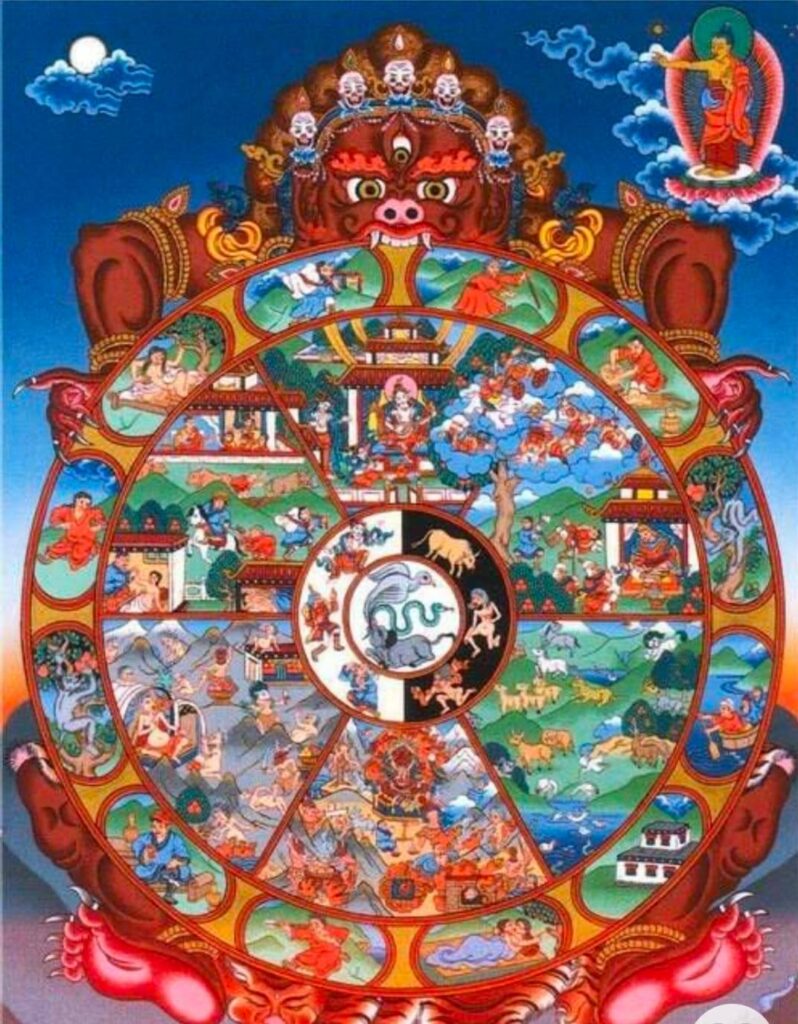

Buddhism, which regards life not as a personal right to claim but as a deeply held value shaped by compassion, karma, and the rarity of human birth. Buddhism is fundamentally concerned with understanding the causes of suffering—primarily attachment—and with overcoming them through the attainment of Nirvana. With this perspective in mind, we can explore how Tibetan Buddhism understands the meaning of life and the ethical considerations surrounding abortion.

Human life, in particular, is regarded as a rare and precious opportunity for spiritual practice and the pursuit of liberation—one that requires an abundance of accumulated merit to obtain.

In contrast to Western ethics, Buddhist ethics is grounded in a nontheistic metaphysics: there is no creator God who judges actions or gives rewards and punishments. The Buddha is understood not as a divine authority but as an awakened teacher whose insights serve as guidance on the path to Nirvana. Individuals are free—and fully responsible—for their own actions of body, mind and speech. Through the law of karma, these actions bring corresponding results with the principle of cause and effect.

In Buddhism, moral ethics and virtue are grounded in the Five Precepts, a set of guidelines for ethical living. These include refraining from killing, stealing, engaging in sexual misconduct, lying, and taking intoxicants.

So, in the case of abortion, the act is understood within Buddhism as a violation of the first precept—the commitment to refrain from killing. For Buddhists, life begins at the moment of conception, when the consciousness enters the meeting of the ovum of the mother and the sperm of the father.

As Karma Lekshe Tsomo explains in her work, “the Vinaya (a set of rules and ethical guidelines for monks and nuns) that proscribes abortion specifically refers to a fetus, which is thought to have consciousness and therefore to be a sentient being. The claim that a human fetus is a sentient being is based on the possession of the five aggregates that are the basis for imputing the existence of a person. This would indicate sometime between the third and the eighth week of embryonic development, when the cardiovascular and neurological systems begin to form. Even though the faculties of an embryo or a fetus are not fully developed, beings at this stage of development have traditionally been regarded as sentient life and capable of feeling.”

This explains why Tibetans add an extra year to your age. So if you’re officially 20, Tibetans are like, “Nope, you’re 21 now.” I mean… we already age fast enough.

In today’s world, the traditional Buddhist code of conduct can feel distant and difficult to apply, largely because it was shaped within a monastic context that does not easily translate to modern lay life. For this reason, I turn to the guidance of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, whose compassionate philosophy offers a more relatable and practical approach for contemporary society.

In His Holiness’s view, he mentioned that “an abortion is basically an act of killing and should be avoided if possible. However, it is difficult to generalize, and each case needs to be judged according to the circumstances involved.” Which makes great sense in the cases of sexual violence and when there is a risk to the mother’s health or life and severe fetal abnormalities. And so forth.

In a qualitative study of induced abortion among Tibetan women in Lhasa by Ciren and Fjeld, some participants discussed religion in relation to their abortion decisions, reporting feelings of guilt and concern about acting against Buddhist values. The study highlights a striking contrast between the influence of Buddhism on elder versus younger women.

For example, Tenzin, a 40-year-old woman from a rural area, described her experience with a trembling voice: “Before the operation, my feelings were, I am not a person, I am a demon (nga mi ma red ’dre rang red). The child just got its hard-earned human body, but I was going to remove it. That was really painful.” Her words reflect a profound internal struggle grounded in traditional religious beliefs about the sanctity of life and the consequences of violating them.

Tenzin believed she had done something wrong, viewing the abortion as harming another being. Yet she added, “When I get better, I will go to the monastery to pray for it,” showing that Buddhism also provides her with a way to find comfort. Through prayers and pilgrimage, she feels she can support the child’s future rebirth and, at the same time, come to terms with an act she regarded as morally troubling.

In contrast, Chokyi, an unmarried 25-year-old, explained that neither she nor most of her generation were strongly influenced by religious teachings. She noted, “Abortion is not allowed from the religious perspective, but I think people who are still alive are more important—the feelings of those people who are still alive.” Less concerned with reincarnation or the status of the embryo, Chokyi interpreted Buddhist values through a lens of compassion for living beings, prioritizing the well-being of those currently alive over abstract religious doctrines.

So in Buddhism, the consequences of any action are understood in terms of karmic results rather than legal punishment or imprisonment. As a well-known Buddhist saying goes, “To know what you did in the past, look at your present body. To know where you will go in the future, look at your present actions.”

In the end, I’m left with the question. If there were a female Buddha, what might her stance on abortion be? Since Buddhist teachings have historically been transmitted and interpreted mainly by men, I can definitely feel it lacking in empathy toward women’s lived experiences. While the tradition often glorifies motherhood, it rarely addresses the welfare or emotional well-being of women who have undergone abortions, leaving an important aspect of women’s lives largely unacknowledged. Thank you for listening to Breaking the Silence. I hope you enjoyed it.

Reference

Ciren, Baizhen, and Heidi Fjeld. “Pragmatics of Everyday Life: A Qualitative Study of Induced Abortion among Tibetan Women in Lhasa.” HEALTH CARE FOR WOMEN INTERNATIONAL 41, no. 7 (July 2, 2020): 777–801. doi:10.1080/07399332.2019.1640702.

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe. Into the Jaws of Yama, Lord of Death : Buddhism, Bioethics, and Death. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006. Accessed November 5, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Langenberg, Amy Paris, ‘Buddhism and Sexuality’, in Daniel Cozort, and James Mark Shields (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Ethics, Oxford Handbooks (2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 5 Apr. 2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198746140.013.22, accessed 4 Nov. 2025.