Ariel Tourmaline

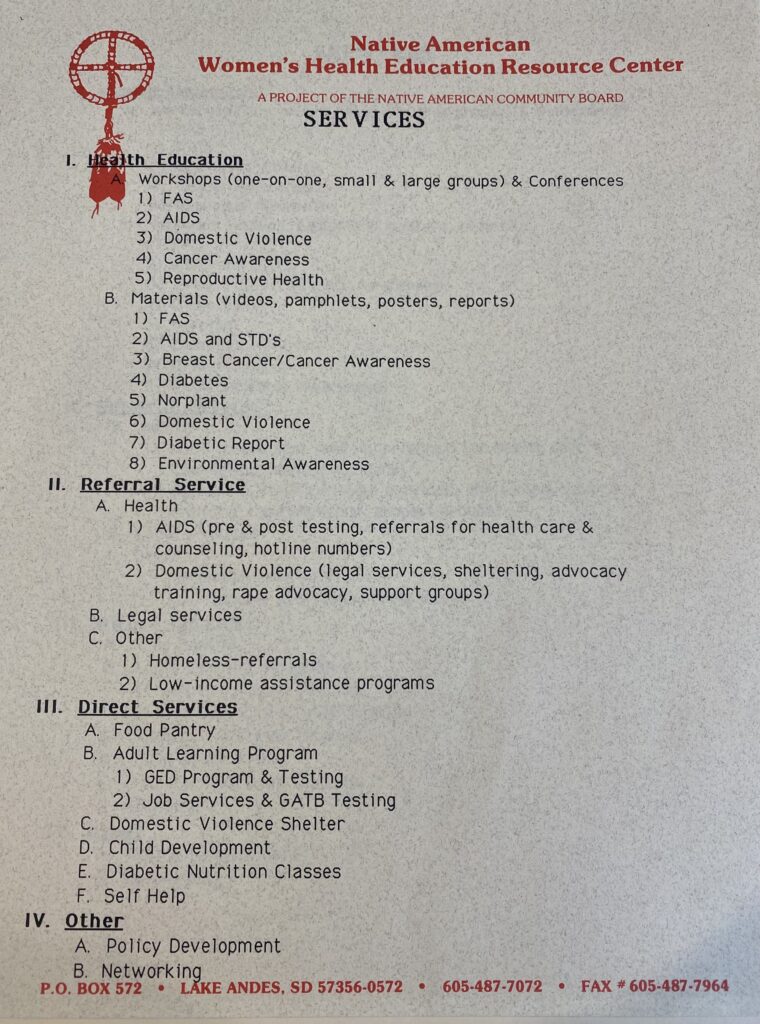

This podcast explores the life and work of Charon Asetoyer, who passed away on September 26, 2025. She was an Indigenous Reproductive Justice advocate who established the Native American Community Board and the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center in Lake Andes, South Dakota, providing extensive programming to meet Indigenous women’s needs in the Aberdeen area, across the nation, and across the globe. Her grassroots efforts provide inspiration and historical insight into addressing reproductive justice violations.

Transcript – Charon Asetoyer: A Life of Advocacy for Indigenous Reproductive Justice

[Intro music]

[Ariel Tourmaline]: As Reproductive Rights in the United States becomes increasingly threatened, we can find inspiration, hope and guidance from activists and collectives who have done an enormous amount of work to fight for human rights and find new and old ways to create networks of care.

[Music fades]

In this podcast I’ll be reflecting on the work and life of Charon Asetoyer who died this year on September 26, 2025. Charon was an indigenous reproductive justice activist who dedicated her life to identifying, researching, and providing extensive programming to serve indigenous women’s health needs locally, nationally, and internationally.

[Music ends]

In 1983 Charon established the Native American Community Board alongside her husband Clarence Rockboy, Everdale Song Hawk, Jackie Rouss, and Lorenzo Dion. The first project to come out of the Native American Community Board was the Women and Children in Alcohol program, that raised awareness about Fetal Alcohol Syndrome aka FAS.

In an interview conducted by Joyce Follet from Smith College’s Sophia Smith Collection, Charon describes how fetal alcohol syndrome is interconnected with a number of reproductive justice issues:

[Charon Asetoyer]: I felt that it was an issue that was plaguing our communities and that we really needed to get a handle on it…fetal alcohol syndrome and all of the residual issues related to it, because you get into children’s issues, you get into education, you get into how women were treated that were chemically dependent and how their rights were being violated, being written off as chemically dependent and no real services for them in order to be able to go into treatment. Still, there’s issues with women who are pregnant going into treatment, women who have children and taking their children into treatment with them. I mean…how are the children going to be taken care of and who’s going to take care of them? And don’t children really need treatment, too, because they have felt the brunt of the chemical dependency within their homes and so forth? …And a child that is adversely affected by fetal alcohol syndrome — how does a mother get her child to hold a fork or a spoon and feed himself? How is a child who’s…affected, what kinds of special education are they receiving in school? What are their needs, and are they being fulfilled? So there is a whole lot of issues that are related to fetal alcohol syndrome and they needed to be addressed.

[AT]: It was through this project that Charon realized how much the indigenous women in the community needed services to support them, as well as their children.

[CA]: When we were still a one room basement office in my home, women in the community were running to the door…banging on the door to let us in because their perpetrator was on their heels, running after them. And so, they were running to us for safety. So then that made us realize, Oh, we need to expand the program and deal with violence-against-women issues and have some kind of sheltering program…and eventually, you know, we opened up a shelter.

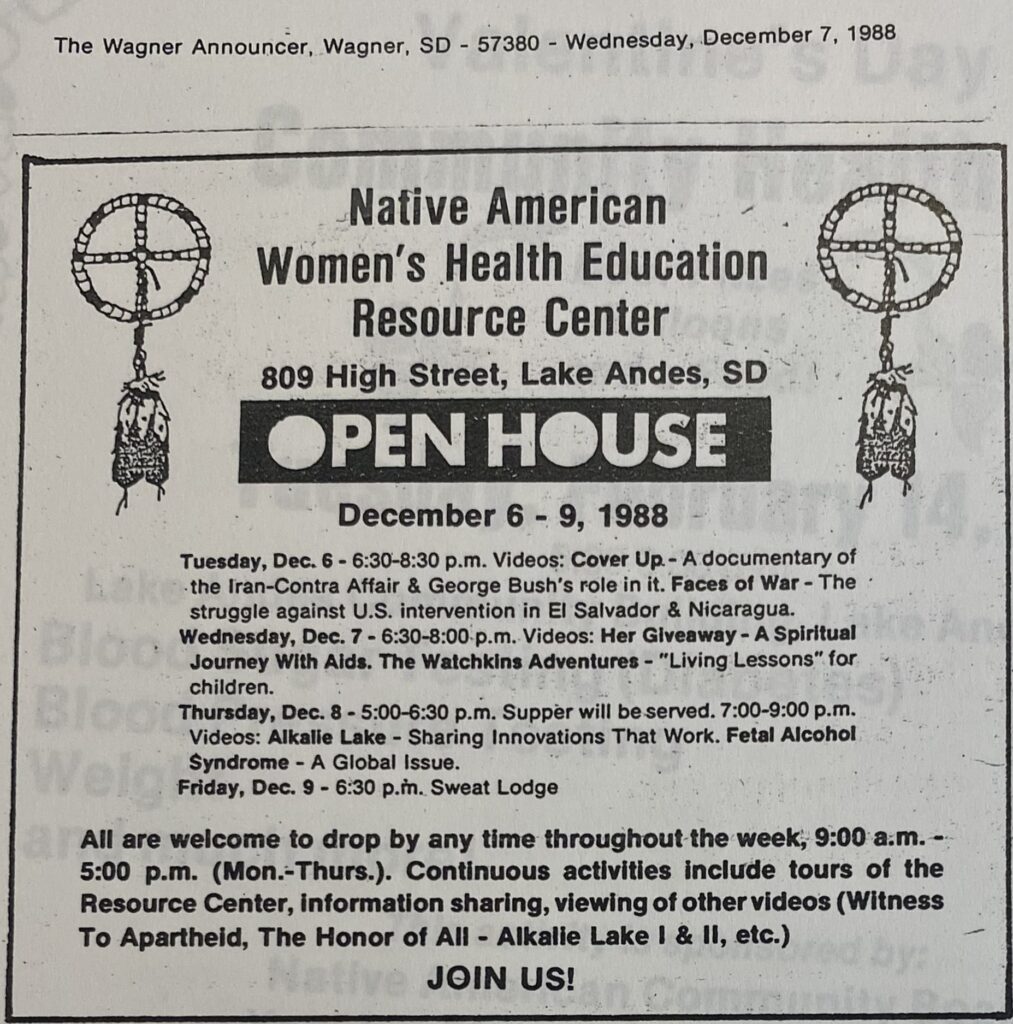

[AT]: She was able to raise funds to buy a house in order to establish the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center.

[CA]: A house seemed like a logical kind of a facility, because we would have women and children coming in and out of here and we needed a fence, you know, because children would be playing out in the yard and…we needed to have a kitchen…you know, we were looking at nutritional courses and addressing diabetes, and so we needed a kitchen to be able to cook and show people how to prepare meals that were nutritionally sound and diabetic-acceptable and so forth. So a home just seemed like a real good building. And then, because we’d have children running in and out, we wouldn’t be disturbing neighbors in other offices. So, if they would cry or play, do what children do, they had the space to do it in.

[AT]: During this time Charon was invited to a conference for women’s health activists and ended up joining the board for the National Women’s Health Network. They were very involved in the fight against the IUD Depo-Provera because it had significant side effects and was being illegally used on women of color.

[CA]: Doctors were feeling very comfortable with using Depo on chemically dependent women, coercing them, and we were very uncomfortable with that because they were not dealing with the root causes of alcohol. They were not dealing with the chemical dependency. They were just saying, we will prevent these women from having children and this is how we’ll do it.

[AT]: The resource center thus expanded their fetal alcohol syndrome program and through international conferences they connected with indigenous women from Nairobi and Tanzania whose communities were also struggling with fetal alcohol syndrome.

[CA]: Grassroots organizing among indigenous peoples you know, in different tribes. So, our FAS work really was not only, it was not just contained in our community. It was among other nations…across Turtle Island and into Africa. And it was very interesting, the politics of alcohol and who was promoting it and how it was being promoted.

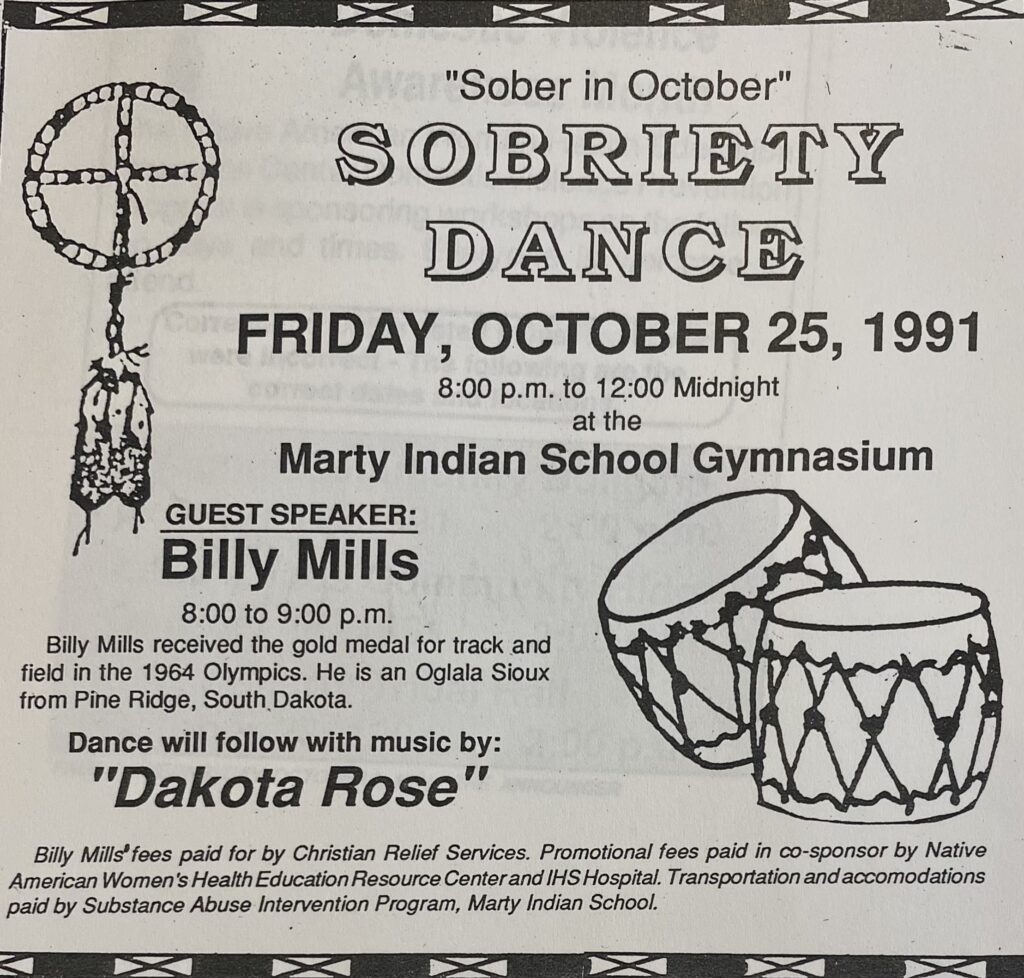

[AT]: In 1990 The Resource Center organized a conference that brought together indigenous women from across the Northern Plains of Turtle Island to discuss the reproductive health issues that were impacting their native communities. This not only brought different tribes together, but also different generations, enabling a resurgence of tribal knowledge and traditions around women’s health that had been lost from the many colonial violences that indigenous communities have endured.

[CA]: Establishing those relationships and sharing information and finding out that we’re not, I’m not the only one who’s seeing this happen in our community. It’s happening elsewhere. So that right there is really important. Also, identifying what are some of the reoccurring issues, and prioritizing those issues.

[Music fades in]

You know, pre-European contact — we had very sophisticated systems in place: our traditional forms of healing, our herbology, our medicines…women were midwives. And we had our women societies in place. And the business of women was just that, the business and matters of women.

[AT]: The conference resulted in forming a committee that meets periodically holding roundtables to discuss Native women’s issues and updating the Indigenous Women’s Reproductive Rights Agenda.

As reproductive rights violations in the United States are worsening, Charon Asetoyer and the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center may have much to teach us about how colonial violence is waged through reproductive rights violations, and how communities can come together to address these issues, in solidarity with each other.

[Music fades out]

References

Asetoyer, Charon. 2005. “Charon Asetoyer”. Interview by Joyce Follet. Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Special Collections, September 1 and 2. Video, 07:00.

Everyone Needs Somebody (instrumental). wevideo, https://www.wevideo.com.

Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center Records. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. Box 1, folders 1-3.

Silliman, Jael, Fried, Marlene Gerber, Ross, Loretta, and Gutiérrez, Elena. 2016. “Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center”. Undivided Rights : Women of Color Organizing for Reproductive Justice. La Vergne: Haymarket Books. Accessed November 4, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Sunny Morning (Instrumental). wevideo, https://www.wevideo.com.

The Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center. n.d. “Welcome to NATIVESHOP.ORG.” Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.nativeshop.org/.

Further Reading

Indigenous Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda

Native American Education Resource Center

Silliman, Jael, Fried, Marlene Gerber, Ross, Loretta, and Gutiérrez, Elena. 2016. “Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center”. Undivided Rights : Women of Color Organizing for Reproductive Justice. La Vergne: Haymarket Books. Accessed November 4, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.