Justine Rogers

This podcast looks at the story of an ICE detention center in Irwin County, Georgia where detained women were subjected to involuntary sterilization procedures. We look as well at some of the history of sterilization abuse in the United States to better understand how forced sterilization matters in reproductive justice.

Transcript

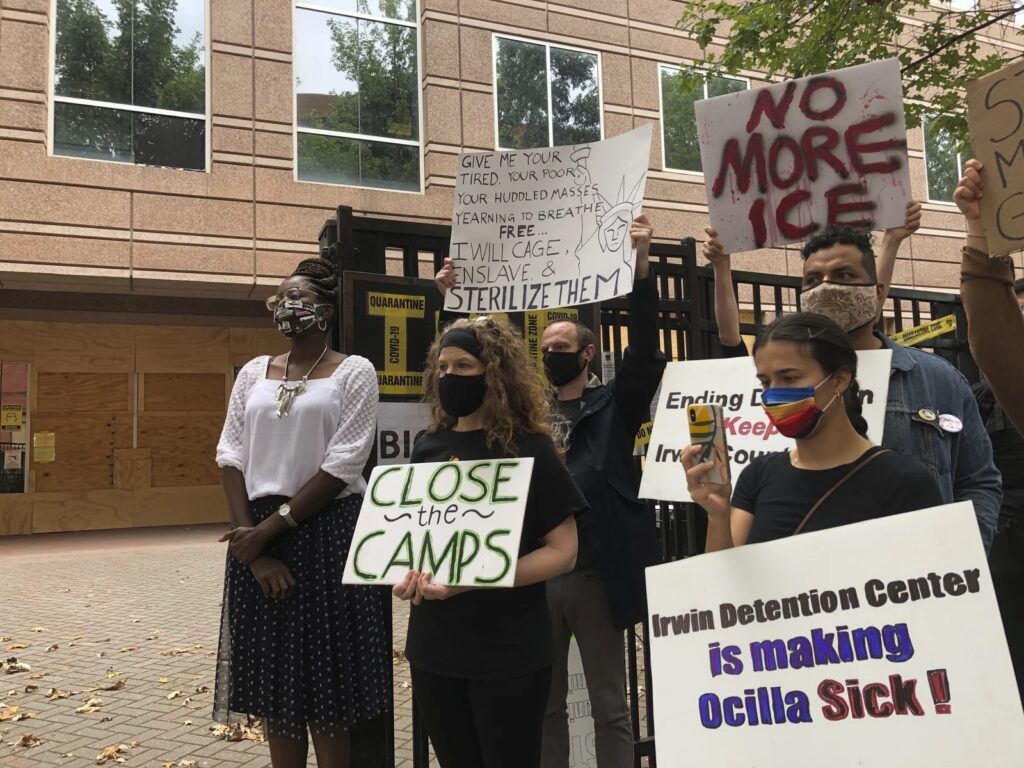

Hello, I’m Justine Rogers and today I’ll be talking about sterilization abuse and forced sterilization. In the United States, eugenics practices have led to reproductive injustices like forced sterilization against women in minority groups for centuries, and these practices are continuing today for the same reasons. In an ICE detention center in Georgia, a whistleblower revealed in 2020 a multitude of accounts of medical negligence and abuse, including that some of the women being held there had been sterilized without their knowledge or consent. This case reflects our country’s history of medical abuse and reproductive injustice and reminds us that involuntary sterilization remains a prevalent issue in reproductive justice.

In September of 2020, Dawn Wooten, a nurse at the Irwin County Detention Center, filed a complaint detailing unjust and dangerous practices at the facility. According to the report, Irwin County Detention Center’s primary gynecologist, Dr. Mahendra Amin, had been performing surgeries removing reproductive organs on women there without their knowledge or consent. Most of the 27 page report focuses on the complete lack of adequate medical care and safe living conditions, which was hugely exacerbated by COVID-19. The medical negligence and lack of care at the facility is more than evident from Wooten’s account. For instance, the facility’s sick call nurse would shred medical request forms from detained women as well as fabricate medical records rather than actually treat those requesting care. The center was also hugely inequipped to follow guidelines for COVID-19, making it an unsafe place for the immigrants detained there.

Along with conditions like these, detained immigrants and nurses at Irwin noticed high rates of hysterectomies performed on the women there. Many of the women were sent to the gynecologist Dr. Amin, even if they did not seem to need gynecological care, and apparently many did not trust him. According to Wooten, just about everybody he saw would get a hysterectomy. The high rate of hysterectomies and sterilization procedures was a red flag, and on top of that many of the women were confused and hadn’t been informed about the procedures that had been performed on them.

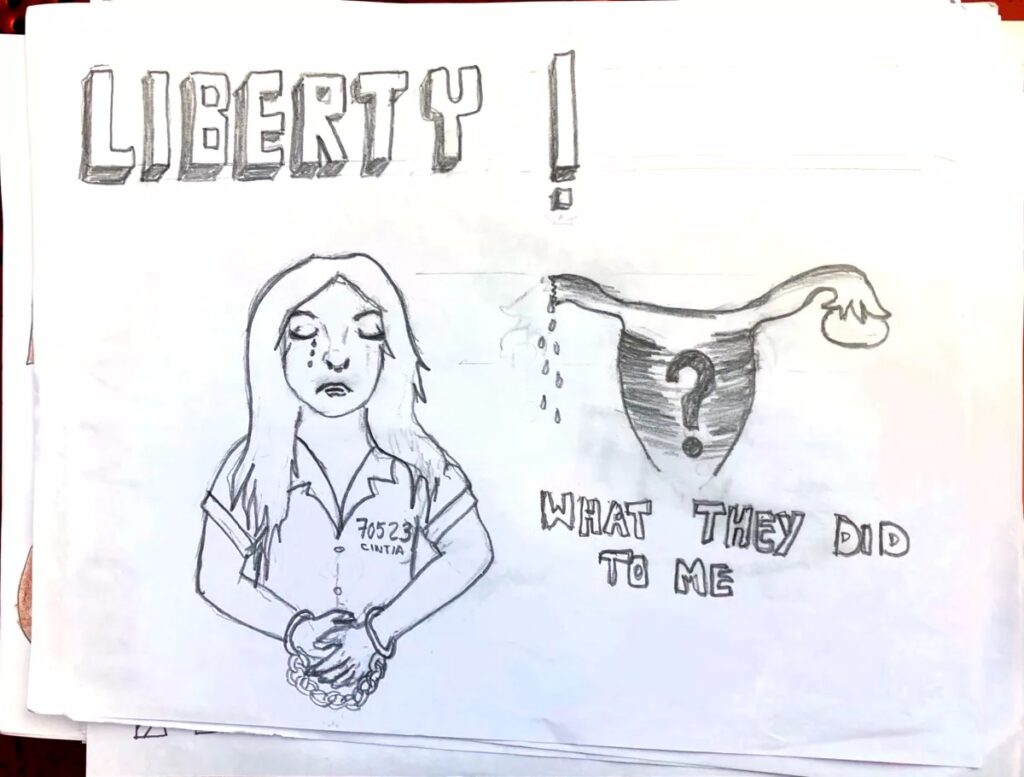

One detained woman reported that no staff or medical personnel could tell her about the procedure she was going to have and why she needed it. This woman received three different and conflicting responses when she tried to ask what was being done to her. The doctor initially told her she would have to have a small procedure drilling holes in her stomach to drain an ovarian cyst. She was then told by a transfer officer that she was going to have a hysterectomy. She was sent back to the detention center from the hospital without being operated on because she tested positive for COVID, and back at the detention center one of the nurses told her that the procedure was going to involve dilating her vagina and scraping off tissue to stop heavy bleeding. When the woman informed the nurse that she did not have heavy bleeding and she had been told something completely different by the doctor, the nurse became angry and irritated, which confirmed to her that something very wrong was going on.

In another case, the doctor was supposed to remove a woman’s left ovary because it had a cyst, but instead he removed the right one, and the woman had to go back to have the left ovary removed as well, leaving her sterilized. She had still wanted to have kids, but that ability was taken from her.

One of the women spoke with others who had had hysterectomies while detained at the facility. After speaking to them, she said “I thought this was like an experimental concentration camp. It was like they’re experimenting with our bodies.”

The lack of knowledge and the fear that these women had about the procedures they received shows that informed consent was not a part of the process, and we can see that in many cases there was no medical need for the procedures that resulted in sterilization. These women’s right to autonomy over their bodies was violated while they were detained at this ICE facility.

In May of 2021, the Biden administration officially cut ties with the Irwin County Detention Center. This is an important step towards ending reproductive injustices, but issues involving racial and medical injustice that can lead to forced sterilization like what happened here are not over.

What happened at Irwin County Detention Center is not an isolated case, and looking at the history of eugenics and forced sterilization in the United States can help understand why something like this was able to happen.

Eugenics emerged in the late Nineteenth century as a form of population control intended to rid society of supposedly undesirable groups and peoples. The practices were informed by white supremacy, and as eugenicist beliefs gained popularity, efforts to control the population led to violations of reproductive rights against women of color.

The ability to forcibly sterilize was granted by the Supreme Court in 1927 with the case Buck vs. Bell. This case upheld the constitutionality of Virginia laws at the time on forced sterilization. According to the court, equal protection under the law, which is guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, did not apply in the case of state-sanctioned sterilization against those who were “feeble-minded.” Many states began incorporating sterilization and other birth control into public health and welfare programs, which allowed them to pressure and force women reliant on these programs into procedures they did not want or need, often without informing them that the procedures would be permanent.

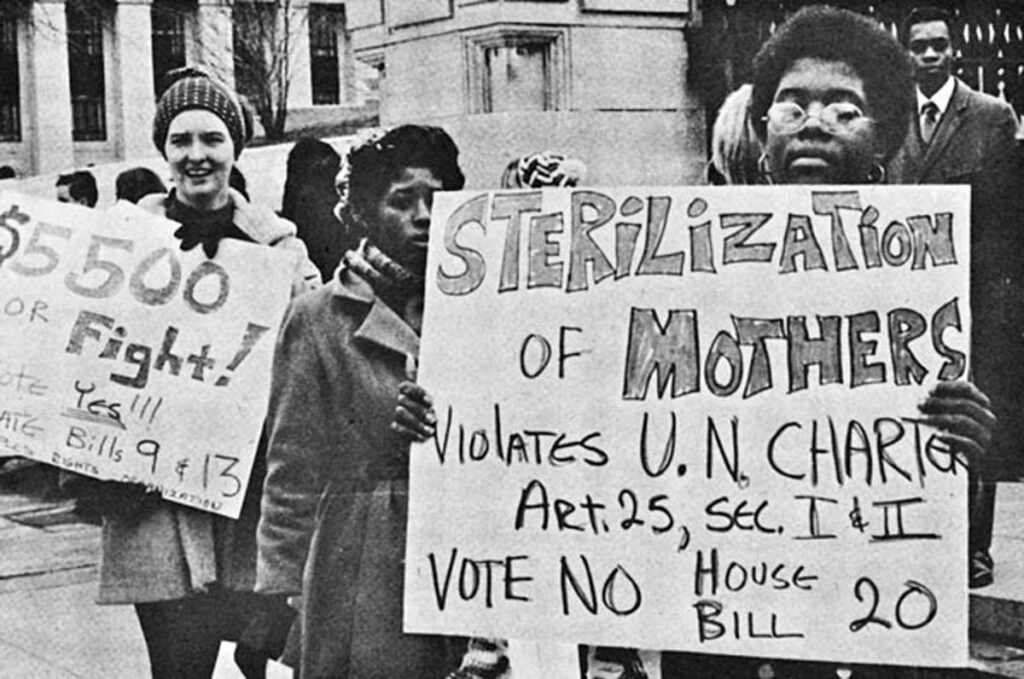

African American, Indigenous, and Latina women were some of the populations most heavily targeted by eugenics and forced sterilization in the twentieth century. This resulted in the efforts of countless women who were affected fighting to bring awareness to the issue and change laws to protect their reproductive rights.

One organization that helped in this battle is the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, which was essential in creating federal guidelines for sterilization in 1979. Doctora Helen Rodriguez-Trias, who helped create the organization, noted the pushback she received from some white women who had difficulty receiving sterilization procedures that they wanted. The different concerns of white people and people of color in regards to sterilization highlights how inherent racism is to America’s practice of sterilization abuse, and how important it is to understand that issues of reproductive justice do not affect all groups in the same way.

While significant strides have been made to stop forced sterilization, it is clear that this issue persists and continues to affect marginalized populations and communities. The ICE detention center in Georgia is likely not the only occurrence of sterilization abuse in the present, but raising awareness about cases like this and fighting to hold the government and private organizations that perpetuate these injustices accountable shows a way forward in achieving reproductive justice for all.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Irwin County Detention Center, you can look at the official complaint, which details a lot of the negative conditions and practices that finally resulted in the facility being shut down.

That’s all for today, thank you for listening!

References

Alonso, Paulo. “The Forced Sterilization of Women of Color in 20th Century America.” Autonomy Revoked: The Forced Sterilization of Women of Color in 20th Century America. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://twu.edu/media/documents/history-government/Autonomy-Revoked–The-Forced-Sterilization-of-Women-of-Color-in-20th-Century-America.pdf.

Cperez. “After Years of Advocacy, Ice Announces It’s Cutting the Irwin County Detention Center Contract-a Huge Win for the Immigrants’ Rights Community.” Detention Watch Network, May 20, 2021. https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/pressroom/releases/2021/after-years-advocacy-ice-announces-it-s-cutting-irwin-county-detention.

Dowe, Wendy. “‘The Traumas of Irwin Continue to Haunt Me’: Non-Consensual Surgery Survivor Seeks Restitution, Calls to Shut down Detention Centers.” Ms. Magazine, December 10, 2021. https://msmagazine.com/2021/12/09/immigrants-ice-detention-center-georgia-irwin-women-reparations-sexual-violence/.

Onyekweli, Nonny. “Reports of Forced Sterilizations Have Prompted America to Reckon with Its Past.” Shondaland, November 2, 2021. https://www.shondaland.com/act/news-politics/a34497969/ice-forced-sterilizations-american-history/.

O’Toole, Molly. “19 Women Allege Medical Abuse in Georgia Immigration Detention.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, October 23, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-10-22/women-allege-medical-abuse-georgia-immigration-detention?utm_source=sfmc_100035609&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=News%2BAlert%3A%2B19%2Bwomen%2Ballege%2Bmedical%2Babuse%2Bin%2BGeorgia%2Bimmigration%2Bdetention%2B-%2B00000175-5399-db98-a77f&utm_term=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.latimes.com%2Fpolitics%2Fstory%2F2020-10-22%2Fwomen-allege-medical-abuse-georgia-immigration-detention&utm_id=16421&sfmc_id=2215007.

“September 14, 2020 – Project South: We All Count, We Will Not Be Erased.” Accessed December 6, 2022. https://projectsouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/OIG-ICDC-Complaint-1.pdf.

Treisman, Rachel. “Whistleblower Alleges ‘Medical Neglect,’ Questionable Hysterectomies of Ice Detainees.” NPR. NPR, September 16, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/913398383/whistleblower-alleges-medical-neglect-questionable-hysterectomies-of-ice-detaine.

Title: Scintilla

Author: Anemoia https://freemusicarchive.org/music/anemoia/

Source: Free Music Archive https://freemusicarchive.org/music/anemoia/exosphere/scintilla/

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode