By Ayla Ladha

In the early 70’s, the Women’s Action Alliance sought to study how sexist stereotyping is engrained in preschool age children. They ended up working with a wide range of schools and daycares to develop tools and methods for non-sexist education in what they called the Non-Sexist Child Development Project. In this podcast, I explore what the project did and how, the results they saw, and how this work has—and hasn’t—changed today.

Transcript

Learning to Unlearn: The Non-Sexist Child Development Project

Intro audio clip from The Sooner the Better: “By not restricting children to sex determined roles, teachers can introduce them to many new options, and can help to give them the physical and emotional tools they’ll need as men, as women, and most of all, as people” (The Sooner the Better).

That was an audio clip from the trailer for the film the Sooner the Better created by the Women’s Action Alliance in the early 70s as a tool for non-sexist education.

What is the project / the WAA?

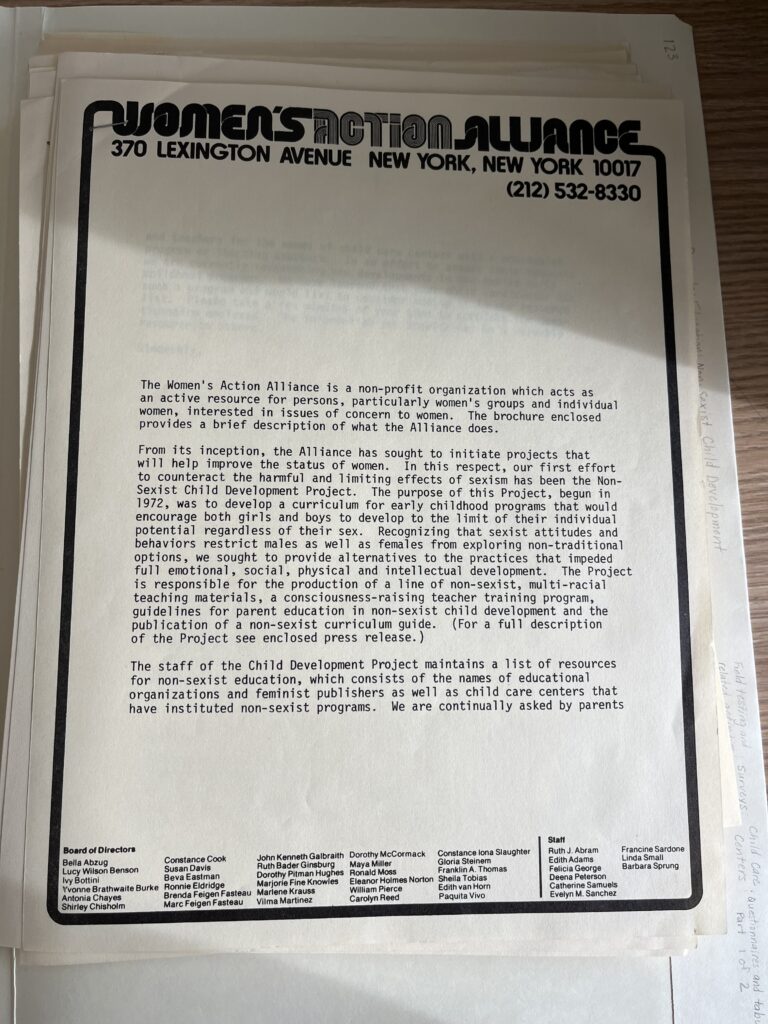

In 1972, the newly formed feminist organization the Women’s Action Alliance began the Non-Sexist Child Development Project, which sought to study the ways in which sexism and gender roles impact and are ingrained in children beginning as early as preschool. This project’s research and resulting recommendations serve as an archive of harmful norms of the time, the growing awareness and response to them, and furthermore are actually still relevant and useful today.

This is Ayla Ladha, and I’m going to be discussing the Non-Sexist Child Development Project—what it aimed to do and how, its impact, and its relevance today. Finally, I’ll also be looking into the new ways in which parents and teachers are approaching issues of sexism and gender with children now.

Teacher and advocate Barabara Sprung, in an article for the journal Young Children in 1975 wrote that parental and societal sexism limits and impacts children from the beginning, “when clothes are bought and rooms decorated in what have been considered sex-appropriate colors and styles” (Sprung, 12). The Non-Sexist Child Development Project began because the Women’s Action Alliance was interested in studying and combating sexism in the incredibly influential years of early childhood—at this moment of the early 70s other organizations were only looking at this issue in older children and teens (Sprung, 12).

The project began with, after a period of observation, the Alliance spending several months working closely with a wide range of daycares and preschools, offering curriculums and materials, and training and teaching parents and teachers. Curriculum goals included how the children were encouraged to behave and act and what they were shown visually (Sprung, 13).

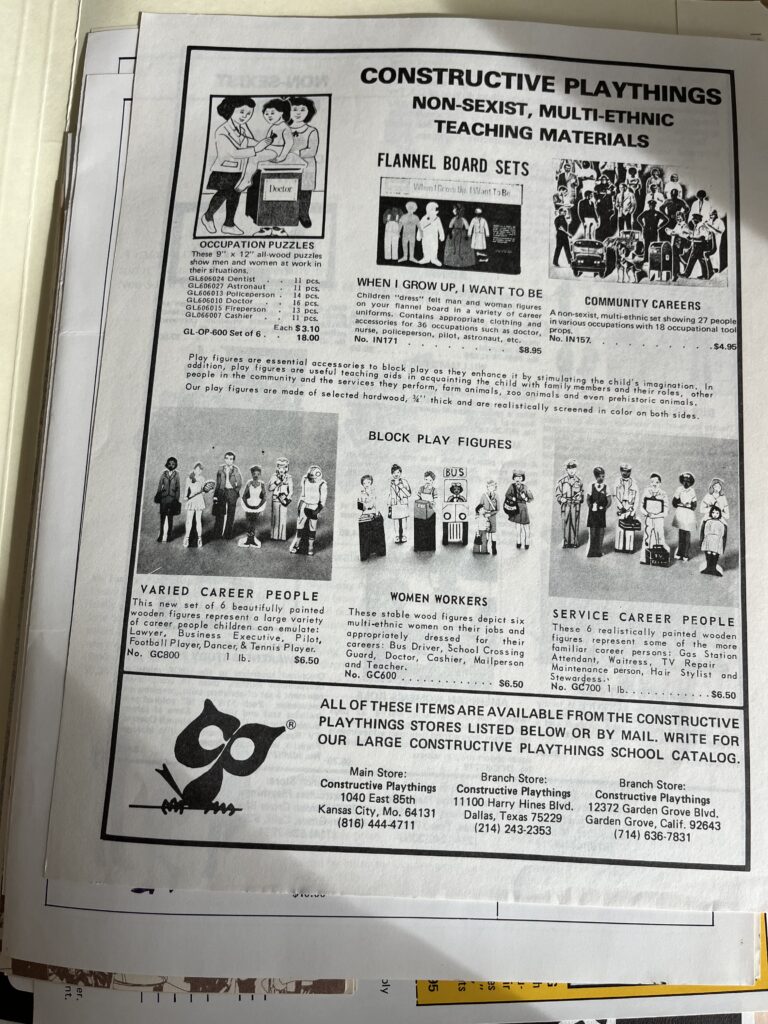

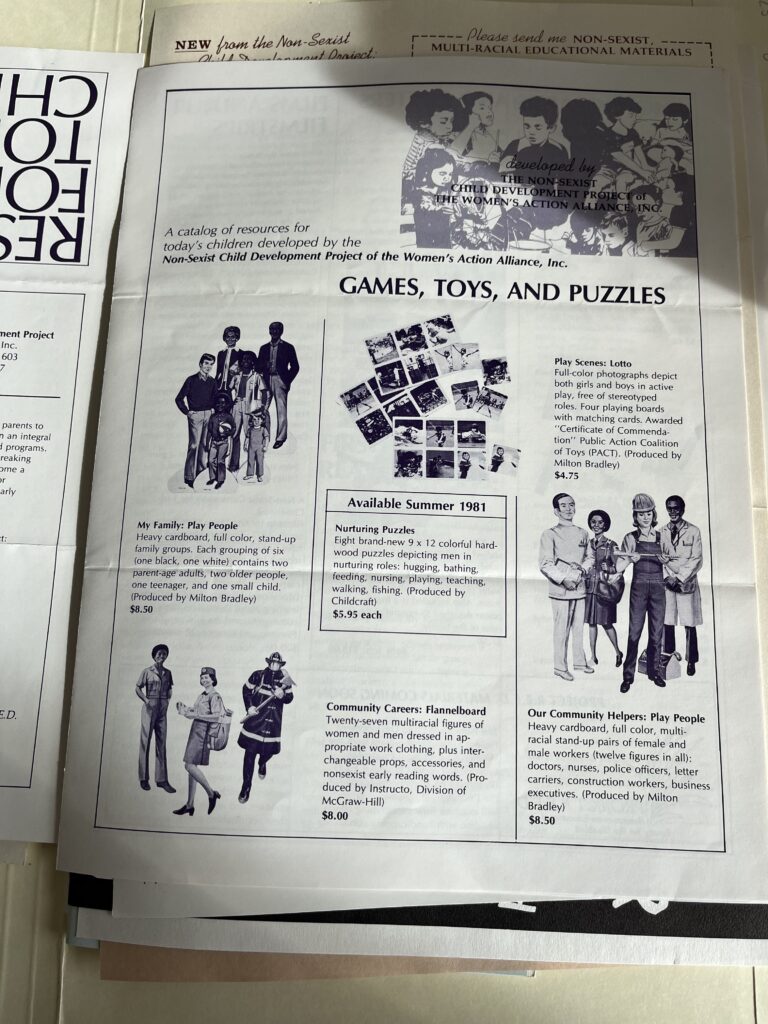

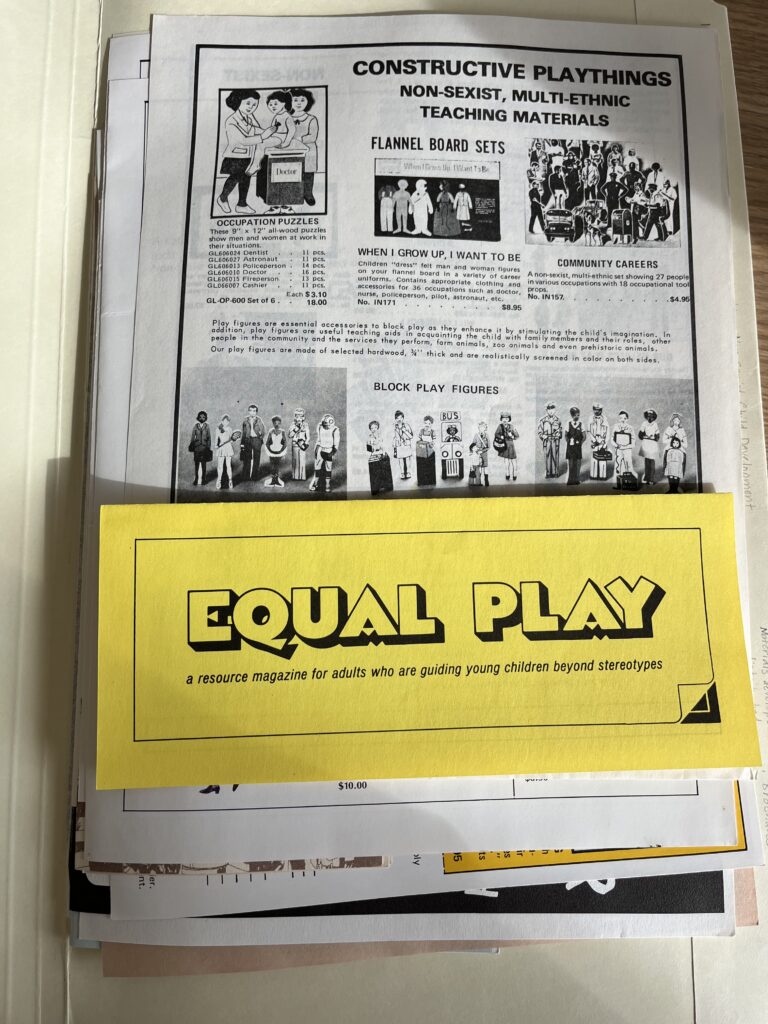

Sprung describes how the usual materials were problematic in that they were not diverse racially and were stereotypical in their representations of gender roles (Sprung 14) ; this is still an issue today if we look at recent discussions surrounding diversity in textbooks and in online image searches, for example. Thus, the Alliance made “nonsexist, multiracial classroom materials” that they even had to make on their own as manufacturers wouldn’t take the risk.

They gave the schools toys, books, games and other materials that they had created or deemed non-sexist (Sprung 15), and they worked closely with teachers to create and help them create non-sexist curriculums. They also worked with parents, but this was a slower change—Sprung described small steps, such as “allow(ing) their boys to engage in doll play within the home but not outside” (Sprung 18). Sprung continues: “Although many parents felt that their own lives would not change much since their sexist attitudes were so ingrained… They were almost all eager and amenable to changes for their children” (Sprung 19).

What did I find in the archives?

In order to further explore the Alliance’s project, I looked at the papers from the project that are archived in our Special Collections at Smith. In “A Brief Introduction to the Non-Sexist Child Development Project”, an summary directed at parents and teachers both, the Alliance lays out the issues they were tackling, including marketing of toys and on television, how children play and what they read, and roles taken on by parents inside and outside of the home. They write: “The less sexist information we allow into our children’s lives… the less they will have to ‘unlearn’ at a later date.” These ideas are so ingrained into “all media”, however, that they explain you cannot fully protect a child from it. Because this change cannot be made societally, the Alliance says that parents have to “take the initiative and begin… in the home”; the document lays out in very accessible language the issues at hand and suggests behaviors, toys, books, language, and attitudes that will help lessen the impact of societal sexism on the readers children. It is also made accessible economically, suggesting various homemade and affordable toys, and considers what can be done when the parents cannot change how they divide labor. This document calls out the many ways in which sexism is communicated to children in society. Television, which was and continues to be a major way young kids spend their time, offers a “distorted view of humanity” and “sexist messages” about the roles of both men and women. The introductory document also discusses the role of language, like excessive use of the word “man” in job titles, and the problematic prevalence and use of “sissy” as derogatory and “tomboy” as positive.

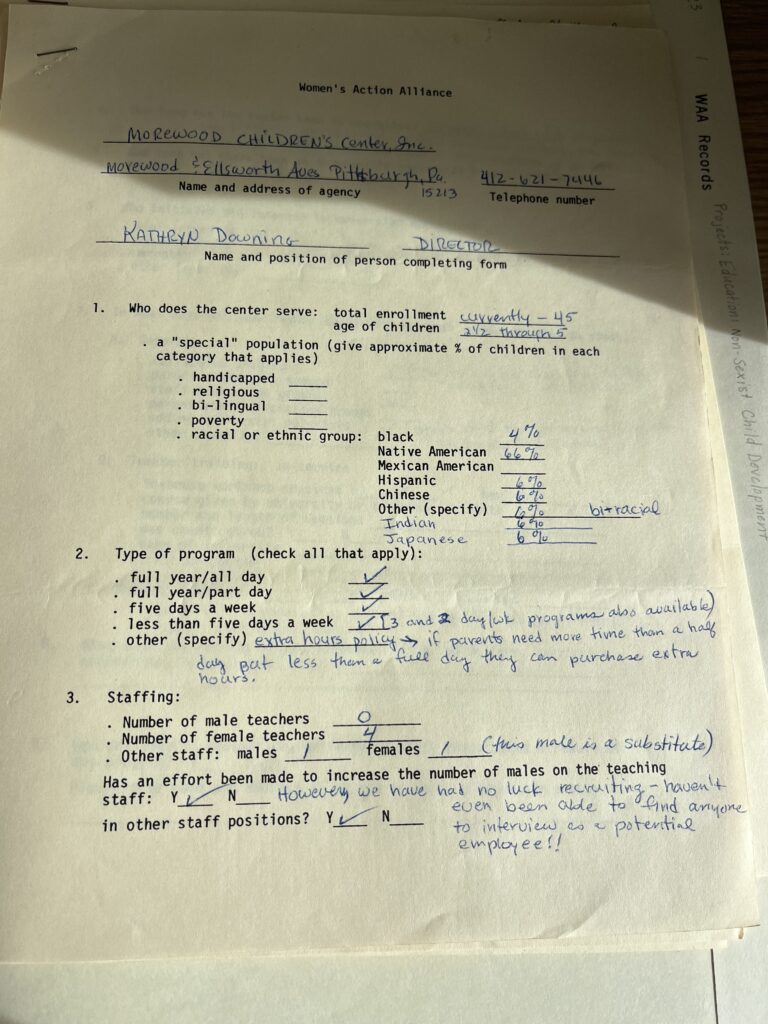

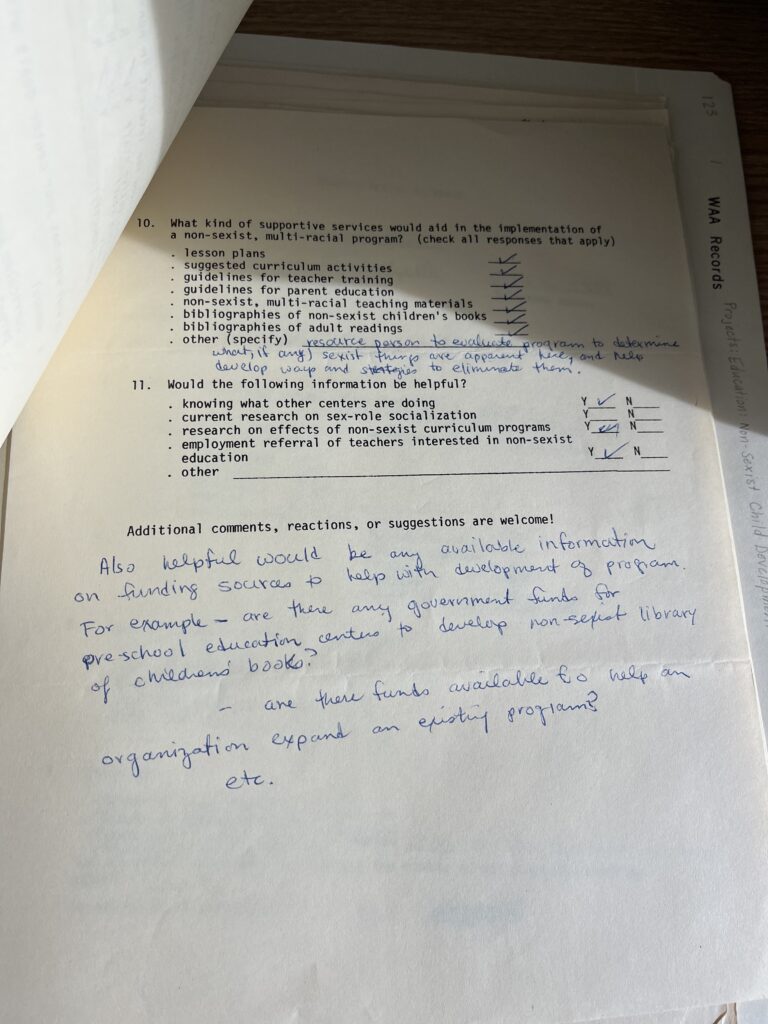

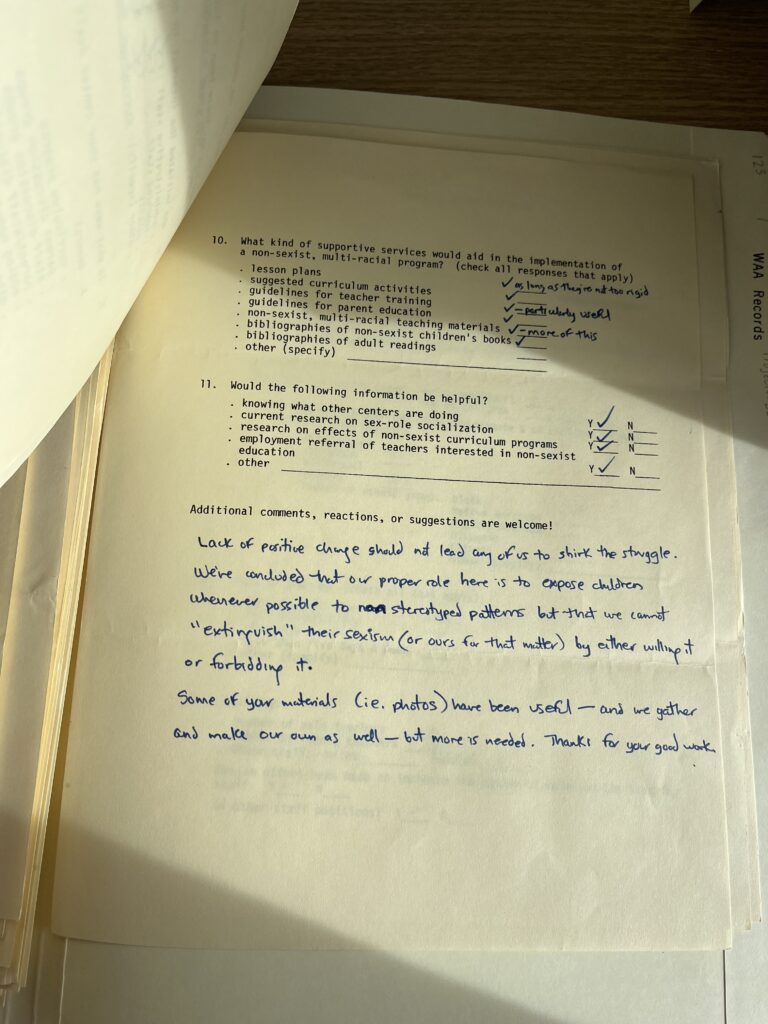

In the archives were dozens of surveys filled out by preschools and daycares looking to be involved in anti-sexist work. I was able to see what types of schools, and who within the school communities, were looking for change, and how that change was being implemented.

The schools overall had a very diverse breakdown of students racially. There was also a lack of male teachers (many schools were trying and failing to find ones to hire or even interview). Finally, it was rarely the parents interested in anti-sexist change.

I was also able to look at the various catalogs of toys, suggested readings, non-sexist and diverse illustrations, and their checklists for non-sexist classrooms. Checklists included what images were displayed, what activities were offered and who engaged in them, and how children were spoken to. There also were summaries of trips and visits.

Another large aspect of the project was their creation of films on “sex role stereotypes” and raising and teaching children, which they distributed to schools and screened to parents. In the surveys, more films were often requested, showing their success. The Smith archives hold materials from the promotion and survey of films The Sooner the Better and The Time Has Come, as well as the suggested script for another unnamed film which would explore examples of different people in children’s lives (parents, teachers) initiating anti-sexism programs, but “what becomes clear is that each group is involved in the continuing process where the aim is to have the full cooperation of parents and staff…in opening up options for children” (Box 123, Folder 13A).

What was the impact?

The work done in preschools by the WAA proved effective. Sprung describes the changes seen in the children. They became comfortable with and excited by women in “nontraditional” roles and jobs, they began to use non-gendered terms such as “letter carrier” instead of “mailman”, and boys, who previously saw dolls as girls toys, became very involved in caring for a boy baby doll. The WAA was also invested in portraying and teaching racial diversity alongside nontraditional gender roles. One school brought in a Black female police officer, and another’s a student’s fathers who was a cook brought in Chinese food (Sprung 19-20). The changes seen in students’ language, behavior, and confidence were undeniable.

What has stayed the same?

Just as many of these issues remain prevalent today, many of the Women’s Actions Alliance’s suggestions are still being implemented. The presence and impact of television, for example, has become much more widely discussed and attended to. There has been positive change, such as increased diversity and anti-sexist messaging, in children’s media, but at the same time advertising and language, for example, remains very gendered. Much of what the project tackled were prevalent issues and conversations in my own experience working with four and five year olds in a day camp setting. Gendered language surrounding words such as “fireman” and “mailman”, fights about who can be a superhero or a police officer, and assumptions about personality traits such as “bossiness” were common, exemplifying how our problematic social norms surrounding gender are still ingrained and thus how it is still important to be actively engaging young children in anti-sexist curriculums and lessons.

What has changed today?

There are many new ways in which we are even furthering this work today. Sweden actually requires “schools to work against gender stereotyping.” In a CNN article covering these schools, Katy Scott writes that gender stereotypes are fully internalized “between the ages of 10 and 14,” and “leave girls at greater risk of exposure to physical and sexual violence, child marriage, and HIV. For boys, the risks can include substance abuse and suicide” (CNN). These preschools in Sweden, for example, use gender neutral pronouns with children, and, as the Women’s Action Alliance suggested 50 years ago, are intentional with language and do not separate any toys into separate areas. Another recent strategy has been gender neutral parenting, which can look like anything from encouraging children to wear any clothes and play with any toys to use of they/them pronouns until the child is old enough to decide for themselves. One parent, speaking to the BBC, explained that part of their intentions with raising their children this way is for them to both understand queer identities and feel safe if they themselves identify as LGBTQ. This is a very controversial parenting style, but so was the Women’s Action Alliance’s work in the early 70s, so it will be interesting to see how it further develops.

Conclusion

Many things have stayed the same, but a lot has also changed. While the Alliance proved in preschools in the 70s that change can occur quickly in the attitudes of individual young children, widespread societal change takes time. We all must work to unlearn and unteach the problematic ideals that are so ingrained in our society in order to achieve equality and liberation; the WAA’s goal in developing this project was to minimize the amount it is learned in the first place, envisioning a future where all parents and teachers might work together to raise children without these attitudes—something that we need to continue to focus on today.

Works Cited / Suggested Readings

“A Brief Introduction to the Non-Sexist Child Development Project,” typescript, undated.

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/152149 Accessed October 30, 2023.

“A Non-Sexist Curriculum for Early Childhood” filmstrips: contracts, correspondence, sales report, 1978 – Box: 123, Folder: 12-14

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/152161 Accessed October 30, 2023.

Brochures – Box:123, Folder: 8

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/151916 Accessed October 30, 2023.

Brochures, leader guides, reviews for films “The Sooner the Better,” “The Time Has Come” and “Sugar & Spice: A Film about Non-Sexist Education” – Box: 123, Folder: 15-17

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/152162 Accessed October 30, 2023.

Child care centers: questionnaires, tabulations, and reports – Box: 123, Folder: 1-3

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/152159 Accessed November 22, 2023.

Departments of Early Childhood Education: questionnaires, tabulations, and reports – Box: 123, Folder: 4-6

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/152160 Accessed November 22, 2023.

General – Box: 123, Folder: 7

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/151915 Accessed November 22, 2023.

“Guidelines for the Development and Evaluation of Unbiased Educational Material,” Felicita George, 1978 – Box: 123, Folder: 10

Women’s Action Alliance Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/151918 Accessed October 30, 2023.

Savage, Maddy. “The parents raising their children without gender.” BBC, October 3, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220929-the-parents-raising-their-children-without-gender

Scott, Katy. “These schools want to wipe away gender stereotypes from an early age.” CNN, November 1, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2017/09/28/health/sweden-gender-neutral-preschool/index.html

SPRUNG, BARBARA. “Opening the Options for Children: A Nonsexist Approach to Early Childhood Education.” Young Children, vol. 31, no. 1, 1975, pp. 12–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42642417. Accessed 19 Nov. 2023.

“The Sooner the Better.” Vimeo, uploaded by Concord Media, October 6, 2015, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thesoonerthebetter.

Below are images from the Women’s Action Alliance records in the Smith College archives.