Ruth Mioc

In this podcast episode, I interview my mother about her experience undergoing a C-section birth while critically examining how systemic structures strip women, particularly those who are low-income and immigrants, of the autonomy to make informed reproductive decisions and to advocate for themselves. I explore what happened to my mother during and after the procedure, including cryptic complications.

Transcript

Ruth Mioc: Hello and welcome to Open Wounds, Closed system. I’m your host Ruth Mioc and on today’s podcast episode, I have a very special guest. My mother, Cristina Ignat. We’ll be discussing my mother’s story of denied reproductive justice.

For some background, at the time of my mother’s story, she had only been in the United States for about 5 to 6 years, immigrating at only 23 by herself from Romania with no family waiting for her here. While reading theory and writing papers is important, what’s equally crucial is listening to and archiving stories. Through the personal narrative of my low-income, immigrant mother, we can see theory in practice.

Throughout today’s episode, we’ll be breaking down a few pillars of reproductive justice. Namely, the right to bodily autonomy showcased by my mother not being informed of her choices before or after childbirth, the right to have children illustrated by the development of early menopause my mother experienced as a result of complications, and the right to have children in a healthy and safe environment as her symptoms of menopause affected her health and she was not able to access or understand resources readily available to others.

To begin, it was March 19th, 2009. While not always the case for some women, my mother’s cesarean section was necessary as the first baby was breech. However, my mother recalls that,

Cristina Ignat: So I was not informed of all the complications I can get in the C-section.

There are a plethora of complications that can occur during C-sections, not that they are completely unsafe in any way, but it is a major surgery. These complications are not necessarily malpractice but in my mother’s case, the first sign of worry was her epidural malfunctioning.

An epidural is an injection into the space around your spinal nerves that allows a continuous delivery of pain medication. However, with my mother, the needle bent, which can injure nerve roots. My mother was aware of this as she recalls,

Cristina Ignat: I was scared after I knew they bent the needle in my back.

Ruth Mioc: Furthermore, as is normal practice, she was fully awake during the C-section. But, she was never asked if she was okay or how she was feeling. Instead, my mother remembers feeling ignored,

Cristina Ignat: And when I was in the C-section operation, I heard them talking, talking about vacations, about things, and I said, oh my God. They were working there like I’m not a human being. I didn’t feel good at all.

Ruth Mioc: Now, it can be normal or routine for doctors to chat about everyday things during surgery, even a C-section where the patient is awake. Nevertheless, this was not the situation. A lack of empathy, not checking in, and not involving the patient or completely ignoring them is not okay. It left my mother feeling like a spectator in her own birth.

The situation then escalated.

Cristina Ignat: And I heard once when they said, “put water, because she’s like hemorrhaging.” Like I think there was a lot of blood.

Ruth Mioc: Hemorrhaging during C-sections is actually relatively uncommon and according to a study published in the academic medical journal “Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology”, excessive hemorrhaging is documented in 5 to 10 percent of C-section cases.

The greatest issue is that after the birth, my mother was not told of the hemorrhaging or complications of the operation. It’s understandable that she was not given a comprehensive list of every possible complication while in the middle of an emergency C-section. But not being told of the complications you specifically experienced after birth is not only unethical, it can carry legal weight. In the framework of reproductive justice, my mother has a right to her autonomy, and that includes being informed.

My father was there for the birth, but in the following days he visited periodically as he had to go to work. Fortunately, my mother had a friend to advocate for her.

Cristina Ignat: My best friend came to visit me at the hospital. She said, “Oh my God, you’re bleeding everywhere.” I was, I had spots on my bed, she called the CNA right away.

Ruth Mioc: Sadly, my mother’s pain was not believed. She remembers talking with a nurse after the birth about her back pain and other birth related issues. She said her pain was at a 10 and the nurse answered along the lines of “you would sit down on the bed if that was true” She had not been sitting because she was continuously taking care of her babies, such as changing and feeding them. Again my mother’s reality was minimized.

Cristina Ignat: I didn’t like her answer because I was a caregiver too, but if somebody’s telling you between one and ten, my pain ten, you don’t answer back, I don’t believe you.

Ruth Mioc: This is actually where systemic structures come in. The health inequalities between men and women can begin to explain my mother’s experience here. There’s an assumption that women are more likely to dramatize their pain. There’s also the belief women can go through childbirth and menstrual cycles, so they can withstand worse pain. Both these notions permeate healthcare. Medicine was once a male dominated field, which inherently can set up a clinician bias that still exists today and creates a lack of effective research on women’s health.

Another factor is my mother’s status as an immigrant. When faced with the possibility of malpractice, it’s very possible that she was taken advantage of due to perceiving immigrant mothers as less likely to sue. At the time, my mother could communicate in English, but not at a comfortable level. In her words,

Cristina Ignat: It was obvious I was an immigrant woman because I was not speaking English that well

Ruth Mioc: Once my mother and my younger siblings were released, another issue surfaced that many Americans can relate to.

Cristina Ignat: When I called them, they said, I can’t help you because you don’t have any more insurance for yourself.

Ruth Mioc: She then had to pay for urgent care out of pocket. Again, not told of resources that existed that could help her cover these costs. The symptoms she was experiencing were unusual.

Cristina Ignat: I didn’t have any more periods. I had hot flushers, very wet sweat, very wet in the night. I was very irritable. And I feel tired.

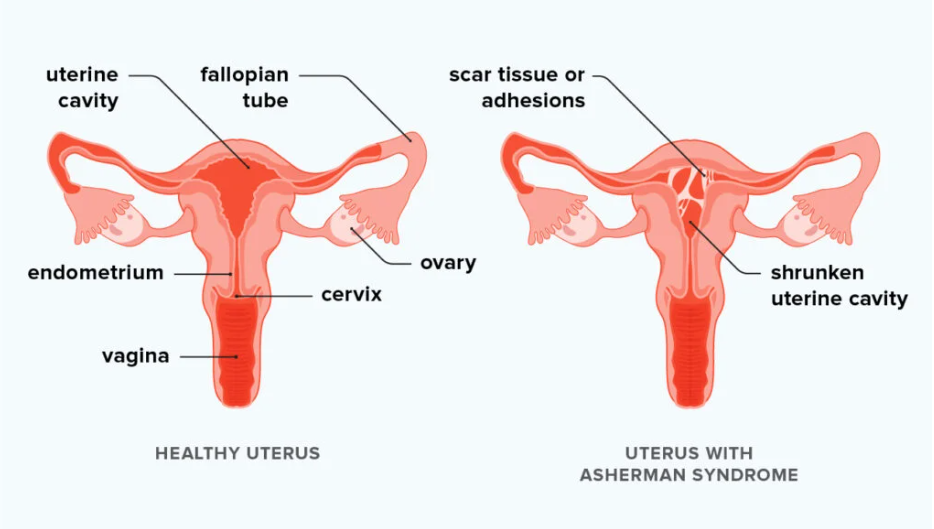

Ruth Mioc: Once in urgent care, the doctor said that she thinks my mother has Asherman’s syndrome. Ashmerman’s syndrome is the bonding of scar tissue that lines the walls of the uterus. It usually occurs after surgery and leads to infertility. Devastatingly, when my mother asked about her options because she was interested in possibly having another child, she recollects that doctor reacting in a disrespectful way.

Cristina Ignat: She was looking at me like I’m crazy. How do I want other kids? I feel so humiliated.

Ruth Mioc: She felt like her right to have children was somehow stripped away. Then my family moved to Arizona and went on state insurance. My mother was able to go to a few gynecologists and did blood testing. A doctor said that,

Cristina Ignat: Your estrogen level is like a 70 year old woman and I was just 34.

Ruth Mioc: The gynecologist also explained that during C-sections, it’s possible to touch ovaries which causes the body to not produce eggs. My mother then remembered her hemorrhaging. She thought that was normal.

Years later when talking with an American friend about the experience, her friend instantly said she should have taken legal action. The systemic barriers of communication issues, financial hurdles, cultural differences, and the focus on immediate needs and daily challenges make this extremely difficult.

Before the discussion with my mother, I felt like a detective and doctor. I found out about cesarean scar defect or CSD, which is a pouch that forms on the wall of the uterus and develops if the incision from past C-sections did not heal completely. But Ashermans and CSD do not directly cause menopause. There is also no history of early menopause in the family and my mother’s symptoms developed right after the birth. After some intensive research, I unfortunately reached the conclusion that, as we have discussed, women’s health is simply egregiously under researched. I tried to find medical answers that may not yet exist.

Cristina Ignat’s story, being that of my mother, hits so close to home, but it’s also been incredibly impactful to see how it related to so many big ideas. Thankfully, I can begin to define the trauma that happened to her. Contextualizing it makes it feel less isolating. But it’s not enough. Thousands, if not millions of women, especially marginalized such as low income and immigrants, can still relate to the feeling of being ignored before, during, and after pregnancy. Like they do not have autonomy and are in the dark about their choices. Reproductive justice must still be fought for, each and every day.

This has been Open Wounds, Closed System. Thank you so much for listening!

References

Mayo Clinic Staff. “C-section.” Mayo Clinic. August 29, 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/c-section/about/pac-20393655

Fawcus, Sue, and Jagidesa Moodley. “Postpartum haemorhage associated with caesarean section and caesarean hysterectomy.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 27, no. 2, April, 2013. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S152169341200140X

Salamon, Maureen. “The dangerous dismissal of women’s pain.” Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard Medical School. July 1, 2025. https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/the-dangerous-dismissal-of-womens-pain#:~:text=Clinician%20bias

Hughes, Dana, and David Smith. “Obstetrical Care for Low-Income Women: The Effects of Medical Malpractice on Community Health Centers.”Medical Professional Liability and the Delivery of Obstetrical Care: Volume II: An Interdisciplinary Review. National Library of Medicine. 1989. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218661/

Portes, Alejandro, and Patricia Fernández-Kelly. “Life on the Edge: Immigrants Confront the American Health System.” Ethical and Racial Studies. National Library of Medicine. August, 2011. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3622255/

Martin, Nina. “Redesigning Maternal Care: OB-GYNs Are Urged to See New Mothers Sooner And More Often.” NPR. April 23, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/04/23/605006555/redesigning-maternal-care-ob-gyns-are-urged-to-see-new-mothers-sooner-and-more-o

Smikle, Collin, and Siva Naga S. Yarrarapu. “Asherman syndrome.” StatPearls. National Library of Medicine. July 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448088/

Solinger, Rickie. “Pregnancy and Power: A Short History of Reproductive Politics in America.” NYU Press. 2005.

Image Credit:

“Asherman Syndrome Diagram”, Courtesy of Medical News Today, Illustration by Maya Chastain

Song Credit:

“Beautiful Daughter”, Courtesy of Audionautix, Composed and Produced by Jason Shaw